Kate Berridge (25 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

The curtain rose and displayed a cave with skeletons and other terrific figures in relief upon its walls. The flickering light was then drawn up beneath its shroud and the spectators in total darkness found themselves in the middle of thunder and lightning. This was followed by the figures of ghosts, skeletons and known individuals whose eyes and mouth were made to move by the shifting of combined sliders. After the first figure had been exhibited for a short time, it grew less and less, as if removed to a great distance, and at last vanished in a small cloud of light. Out of this same cloud the germ of another figure began to appear, and gradually grew larger and larger, and approached the spectators till it attained its perfect development. In this manner, the head of Dr Franklin was transformed into a skull; figures which retired with the freshness of life, came back in the form of skeletons, and the retiring skeletons returned in the drapery of flesh and blood.

In a terrifying climax, instead of advancing and receding in front of the audience, the spooks and spectres suddenly charged towards them. The startled spectators shrank closer together, fingernails were dug into hands, and screams were shrill in the air, though the less timorous reached up to try and touch the menacing mirages.

Sometimes Philipstal undertook private performances in the homes of the wealthy. On one occasion he was engaged by âa man of fortune' in Portman Square, off Baker Street, to entertain a group of friends including a number of young ladies. Unfortunately although the finale was supposed to be the hair-raising, heart-stopping highlight of the show, on this occasion things did not go as planned. As a newspaper reported, âOn the very first appearance of the spectre the ladies were thrown into fits andâ¦it was in consequence of this circumstance that he thought it proper to stop the exhibition.' The

report is an account of the ensuing legal action brought by the showman against the gentleman who had booked him, the latter having refused to pay the full fee for such an abbreviated performance. Although the parties are not named, circumstantial evidence indicates very strongly that the showman concernedâdescribed as an expert in the âdeception of the spectrological arts'âwas Philipstal. In one of the letters in the scant correspondence with her family in France that miraculously have survived, Marie makes mention of his involvement in a legal dispute that could well be the one outlined here. This incident also fits a picture that can be pieced together from disparate fragments of information about him as a difficult, contentious man. The evidence is of a career studded with litigation, lies and let-downs, and a tendency to disappear and reappear in other people's lives with the unpredictability of one of his own creations. Yet, redeeming his reputation, the dislikeable magic-lantern maestro must take credit for importing Marie's talent to London, thereby helping to lay the foundation for the future national and international entertainment empire.

Though Philipstal and Marie offered seemingly unrelated entertainments, they both catered to a burgeoning interest in likenesses of the famous. A contemporary account of Philipstal's performances by a man called Nicholson, who seems to have attended them regularly, describes how they featured âsemblances of several great heroes and other distinguished characters'. He writes, âMr Philipstal's performances are not wholly confined to “men that were”; he occasionally introduces great and distinguished characters of the present day; the compliment paid to our gallant Lord Nelson in crowning him with laurels being particularly well conceived.'

This experimentation with animated likenesses of living and dead heroes and celebrities could be seen as the distant ancestor of cinema. The low-tech images projected by Philipstal were an embryonic form of the sophistication achieved in movies with actors and actresses in different roles. In each case a large part of the pleasure for the audience lies in the interplay between representation and reality. But whereas today the stars of the big screen are generally rated for their ability to play many different characters in a convincing manner, making us forget their âreal' identities, in Georgian England what was

so utterly compelling was simply the evocation of the actual person. It is hard, in the twenty-first century, constantly bombarded with photographic images, to recapture the sheer magic of any representation. For us, jaded as we are with seeing reality reproduced, it is the quality of the reproduction that matters. For Philipstal's audiences, in contrast, likeness itself was the buzz.

As manufacturers of likeness, Philipstal and Marie were lauded for their ingenuity. Some thirty years before Daguerre used light to capture likeness, becoming a pioneer of photography, with his magic lantern upstairs at the Lyceum and with her wax figures downstairs Philipstal and Marie were tapping into the thrill of the mimetic. In using their talents for this form of replication of the famous and infamous, they were continuing what Curtius had done so successfully in Paris some twenty years earlier, exploiting and profiting from the nascent cult of celebrity. âVide et Crede'ââSee and Believe'âwas a popular slogan among showmenâMarie herself used itâand this challenge to come and behold their wonders was often a tag line on handbills. For those who went to the Lyceum in the season that Marie and Philipstal were there, their first experience of the moving and static facsimiles of real people was incredible, and they could not believe their eyes.

Scotland and Ireland 1803â1808

T

HE HIT THAT

Marie had with her likeness of Despard should have pleased Philipstal, confirming his hunch that the fashionable fun-seekers of London would love her work. But just as she was getting into her stride he decided unilaterally that they should move north, to Edinburgh. How much petty jealousy played a part in his insistence in moving Marie on is unclear. He was a man who easily felt threatened. In January 1802, in an attempt to assert his superiority in the magic-lantern market, he registered a patent for his equipment. He was keen to distinguish his own entertainment as the original and best phantasmagoria in the midst of a crop of imitators. Emblazoned on his handbills were the words:

Â

Under the Sanction of His Majesty's Royal Letters Patent

PHANTASMAGORIA

This and every evening till further notice

At the

Lyceum, Strand

As the advertisement of various exhibitions under the above Title, may possibly mislead the unsuspecting part of the public (and particularly strangers from the country) in their opinion of the Original Phantasmagoria, M de PHILIPSTHAL, the Inventor begs leave to state that they have no connexion whatever with his performances. The

utmost efforts

of Imitators have not been able to produce the Effect intended, and he is too grateful for the liberal encouragement he has received in the Metropolis, not to caution the Public against those spurious copies, which, failing of the perfection they assume, can only disgust and disappoint the spectators.

Â

Magnanimous though this may sound, it was not only to protect the public from disappointment that he was registering a patent: he was

increasingly alarmed about the competition. A growing concern was that phantasmagoria fever was leading to phantasmagoria fatigueâanother reason to head north.

The unforeseen disruption of the move from London may have been tinged with some relief for Marie once she heard about the imminent opening in the upper theatre of a Mr Frederick Winsor, a German showman-scientist. His âact' comprised a demonstration of gas for the purposes of illumination. This form of light entertainment entailed not just gas-lit chandeliers in the upper theatreâor what he described as âaeroperic branches'âbut a dramatic illumination of the whole building. It was dazzlingly obvious to Marie that fiery bursts of flame and furnaces in proximity to her wax figures would be a perilous arrangement. So, while Winsor was installing his gas lighting, Marie was presumably happy to be packing up her crates in the lower theatre in readiness for her departure. What happened on Mr Winsor's opening night confirmed her worst fears. The auditorium quickly became a fug of noxious-smelling fumes which made the audience runâin some alarmâfor the exits. âIt will be the last GAS-p,' mocked the press. But they would eat their words, for Mr Winsor withdrew to his workshop in Hyde Park and, with patience and evangelical commitment, eventually developed a system of metropolitan gas lighting that transformed the lives of Londoners. By the time Marie revisited London, in 1816, twenty-six miles of gas mains had been laid, and the novelty of gas lamps was such that people pursued the lamplighters on their roundsâmore interested in looking at the lamps themselves than in seeing by them.

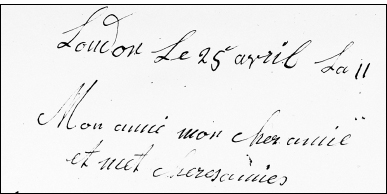

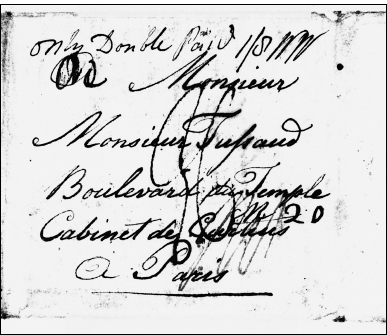

The date for Marie's departure for Scotland was set as 27 April 1803. In her final days in London, with the contents of her exhibition safely boxed, she seems to have had a pang of homesickness, judging from the contents of a letter to François dated 25 April. In this, the earliest of the surviving correspondence between them, she is writing to him at the Cabinet de Curtius, 20 Boulevard du Temple, from her lodgings at 2 Surrey Street. She tells him how receiving his letters gave her great pleasure, but also made her miss himââNini [nickname for Joseph] and I cried with joy and sadness at not being able to embrace you'âand later in the same letter she promises that as soon as she has a new address in Edinburgh she will let him know it. âI implore you

my love to reply to me at once as your letters are the only consolation in a place where I know no one. I will end by embracing you a thousand times.' Feelings of loneliness are exacerbated by being in transit, but also compounded by a lack of support from Philipstal. âHe treats me as you do, he has left me all alone. It is better so, as he is angry about everything.' There were evidently wrangles about the transport arrangements for the exhibition. Adding to Marie's burden, Philipstal was not going to be travelling with her: he had unfinished business in London and would come on later. Reiterating isolation, she says plaintively, âI must travel all alone.'

Her letters are extremely rare opportunities to hear Marie's own voice. But they reveal moreânotably that she was uneducated. The writing, with loopy lettering, is often illegible, and words wobble over the page in slopes not lines. The language seems to be almost a patois of French and German, and spelling and grammar are similarly inconsistent. Perhaps the reason she tends to write in effect a round robinâmost of her letters open âMy friend, My dear friend, and My dear friends'âis because of the sheer difficulty that expressing herself on paper entailed. Another possibility, borne out by the way she lapses into third-person references to her aunt and mother even though she is supposedly addressing them directly, is that they could not read and she relied on François to read out to them her news. This would also account for the inclusion of more intimate expressions of affection to him that he could read to himself.

This correspondence is tantalizing for being one-sided: none of the letters from François survives. However, from her letters and legal documents, it is possible to deduce that back in Paris he was mired in financial difficulties. The day before Marie embarked for Edinburgh she visited Mr George Wright, a solicitor at 41 Duke Street, Manchester Square, to draw up legal documents assigning to François full power of attorney and authority âto borrow what seems good on the best terms he can, all the money he requires and to compel his said wife to join with him completely in paying the capital interest laid down in any transaction'. With this document she was putting in jeopardy all that remained of her inheritance from Curtius. What induced her to such rash relegation of power to a man who she knew was an unreliable bungler is unclear. Presumably she was complying

with a request from him to assist in obtaining further loansâa compliance no doubt influenced by her young son, Francis, and her mother being in his care, and for their sakes she could not refuse him. With this significant piece of administration behind her, she left London, a city she would not return to for fourteen years.

As she made her way to the busy wharves to embark on a boat that would chart a slow course along the east coast of England, she was leaving a city that was straining with growth. London was the first British city with a million inhabitants. The river was the place to sense the expansion. It was a building site of warehouses, and an inadequate number of docks were congested with cranes and a forest of masts belonging to ships trading in every conceivable cargo and commodity. Mooring space was permanently short, and before they set sail some ships were so heavily laden that they lay low in the water and the passengers had to board them by descending ladders. Livestock were lowered with ropes, winched aboard in canvas cradles, and a strange sight was airborne horses, ungainly bundles with sprawling legs, swivel-eyed with panic as they were lowered on to the deck. But before Marie reached the warehouses and the tidal road that was the Thames there was the clatter and hubbub of wheels and hooves, with every jolt and lurch reminding her of the fragility of her exhibits. The streets of Georgian London were a constant turmoil of trafficâcarts, chaises and coaches. Wheelwrights, saddlers and farriers and the smell of manure reinforced the impression of a city reliant on horsepower. Given that her original purpose was to remain abroad only long enough to generate sufficient funds to restore the financial health of the family business, she probably believed she was leaving London for good. She could not have the faintest inkling at this stage that this city, not Paris, would be her home.

The timing of her departure proved fortunate. In a popular contemporary cartoon, the illustrator Gilray satirized the precarious Peace of Amiens as an illusory phantasmagoria, and its flimsiness was finally proved when, just two weeks after Marie left London, after much diplomatic wrangling the treaty finally collapsed. On 17 May England declared war on France, resuming a conflict that would last for another twelve years. As a citizen of the enemy country, it could have been compromising for Marie to reside in London. New legislation imposed

travel restrictions on âforeign aliens', and vilification of all things French was the principal theme of a vast propaganda offensive at this time.

As it was, after a queasy journey with collective

mal de mer

, by 10 May she was acclimatizing to Edinburgh, a city where there were plenty of compatriots. Well-connected émigrés who had fled France in fear of their lives had colonized this gracious city, the most illustrious of them being the youngest brother of the late King Louis XVI, the Comte d'Artois (later Charles X). But, while he weathered his exile in the grandeur of Holyrood Palace, Marie settled into the humbler surroundings of rented accommodation in the city centre. It appears that not heeding the famously sentimental advice penned by the Scottish bard Robbie Burns, âShould Auld Acquaintance be forgot', Marie had forgotten her erstwhile court connections, or they had forgotten her, for her time in Edinburgh shows no fraternizing in émigré circles using her links with Versailles as an entrée. There is no hobnobbing at Holyrood, but rather a woman entirely committed to the hard graft of making her mark with a travelling show, and overly grateful for any encounter beyond the community of showpeople. There was, however, one old acquaintance in her midst who came through for herâMonsieur Charles.

A month before Marie arrived, Monsieur Charles was bestowing upon the people of Edinburgh the great privilege of an opportunity for an audience with the Invisible Girl. He whetted their appetite with elaborate hyperbole (or one might just say hype) in the

Edinburgh Evening Courant

. This was no ordinary entertainment, but âThe Only True Original and the Most Incomprehensible Experiment that has ever been witnessed in the World'. His ethereal leading lady was variously described as a âLiving aerostat' and a âMysterious incognita'. The extravagant claims are a match for the list of patrons. The people of Edinburgh, in extending their patronage, would be joining vertiginously elevated ranks of cultural cognoscenti, for Monsieur Charles assured the public of the presence of âHis Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, distinguished personages and philosophers in England and Scotland' at previous performances. Perhaps most extraordinary of all was that a world-class act with such a prestigious clientele should be available at so modest a location as 63 South Bridge Street. But such dichotomies and anomalies never seemed to deter the public.

Still rocking from the motion of the boatââwith a bad head as though I was on board'âon 11 May Marie wrote home. She describes a rough voyage, with even seasoned sailors succumbing to seasickness, made worse by the necessity of keeping below deck because of the swell. There are rare glimpses of maternal feeling and pride at her small son's plucky behaviour on rough seas that earned him the nickname âLittle Bonaparte'. âThe boat rolled in the most terrifying manner and the captain who has made this voyage a hundred times said he had never seen anything like it. But Monsieur Nini was not afraid. He made friends with the captain and everyone else. In fact the captain wished he had a child like him.'

In the same letter we learn the extent of Monsieur Charles's friendship to Marie in adversity. The spat with Philipstal over transport costs had evidently escalated to such a pitch before her departure that she nearly abandoned their partnership. âI threatened to return to Paris and when he saw I meant business he gave me £10. One has to be wary of Philipstal.' On arrival it transpired that his grudging handout had been insufficient to cover the travel expenses of £18. âIf I had not found Mr Charles we should have been obliged to lose all. Monsieur Charles has lent me £30.' He gallantly assured Marie that he would extend the run of his own show for as long as it took for her own exhibition to be safely installed. She discovered that the pitching of the boat had resulted in thirty-six breakages to her precious cargo, and the necessary repairs added a considerable pressure to the already onerous workload of settling in and setting up. She lost no time. In two days she had rented rooms suitable for the exhibitionââa nice salon well furnished and decorated for £2 a month'. She intended to lodge on the same premisesâBernard Rooms, Thistle Street. The bonus of her landlady, Mrs Laurie, being able to speak French and the fact that she had found an interpreter fluent in German, French and English who could help with marketingâwording advertisements and copy for cataloguesâand most importantly who could act as a guide, contribute to a buoyant tone. These new contacts and her growing friendship with Monsieur Charles alleviated the isolation that had tipped into loneliness in London.