Kate Berridge (5 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

One important function of wax figures was as an illustrated supplement to the news of the day. The ballad singers on the streets were a valued broadcasting service. From royal sex scandals, to sensational murders and executions, they were a popular source of gossip, scandal and news. Curtius supplied for people's eyes what the balladeers gave their ears, and seeing the public's appetite for even the smallest crumbs of information about topical events instilled into Marie a life-long commitment to ensuring that the waxworks were up to date. Mercier noted that songs detailing the bloody acts and horrid deaths of criminals were always big hits: âSome well-known personage ascends the scaffold, his death is set to music at once with violin accompaniment.' Curtius exploited this interest with his visual version of the sensations of the day.

At the Palais-Royal the waxworks were an elegant recreation of an aristocratic salon, and the central attractions were tableaux of the royal family. This was the classiest of Curtius's various sites, and the

plus-

snob style was achieved by a tiered admission system. As a writer in the early nineteenth century relates, âThe price of admission was two sous, but for twelve sous the public was permitted to approach and circulate near the figures, and though the charge was so moderate, Curtius's receipts were 300 francs daily.'

Then as now, people clamoured to get close to the most influential people of the day, and relished their chance âto mingle with the mighty'. In the early days of the exhibition the latter included the military hero General Lafayette, who did so much to popularize America in France. (Later, however, Marie, in a rare expression of an opinion, felt his allegiance to the colonists had been misguided. âWell-meaning short-sighted mortal! How little did he foresee the dreadful effects which ever must arise from suddenly conferring liberty on an enslaved and uneducated people!') In silent company with him was the man whom Marie regarded as his accomplice in bringing down France, Benjamin Franklin, of whom she said, âTo Dr Franklin's visit to France may be attributed the primary cause of the French Revolution, as Lafayette was not alone in becoming a disciple

of the transatlantic philosopher.' But not all the figures were controversial. Instead of propagating republicanism, the naturalist Buffon cultivated popular interest in the natural world. And when people were not crawling on the earth to study caterpillars they were gazing at the sky, as Paris was gripped by balloon-mania. Aeronauts were a new species of celebrity, and Curtius's wax tributes permitted life-size scrutiny of these pioneers normally seen only high high up and far away. Also on show when they were the talk of Paris were Mesmer and Cagliostro, the charlatan gurus who hoodwinked high society with their pseudo-scientific alternative-health claims.

Whereas in real life an invisible cordon segregated the classes, the faux exclusivity of the waxworks was an affordable and amusing way to infiltrate the usually private circles of privilege and the rarefied exclusivity of the court of Versailles. Curtius's salon became a regular fixture on tourist itineraries, and was highly recommended in the growing number of consumer-oriented publications in which there was a new emphasis on fashionable pursuits rather than antiquities and heritage sites. It became a must-see destination, and was very much à la mode.

The almanacs that were guides to what was on in Paris made frequent reference to Curtius's exhibitions. A prolific contributor to these publications was François Mayeur de Saint-Paul. In 1782 he praised the realism of Curtius's coloured heads, âwhich appear to be living. One can see these heads in his Boulevard du Temple cabinet and at the Saint-Laurent and Saint-Germain fairs, where because they can obtain this pleasure for two sous they attract a great crowd of curious people from all classes.' He was also impressed by how the waxworks kept up with current affairs: âEvery unusual event gives him the opportunity to add to his collection.' Later, the 1785 edition of a publication entitled

A New Description of the Curiosities of Paris

recommended the Palais-Royal exhibition as a âspectacle well worthy the attention of people of respectability and position'. The next edition of this publication reveals how it was public interest that was the chief criterion for the choice of figures shown: âOne may see here the figures of all celebrated personages representing all ranks of society from Voltaire to M. Deduit who writes verses and sings them at the cafés of the boulevards.' Public opinion was Curtius's guide, and it was

becoming a powerful authority: the Swiss businessman and French finance minister Jacques Necker described it as âan invisible power that without treasury, guard or army gives its laws to the city, the court and even the palaces of kings'.

In catering to all sections of society, Curtius was part of a process distinctive in the final decades of the

Ancien Régime

, when the chasm between elite culture and popular culture began to close. In much the same way that people dressed up and dressed down, causing confusion over their rank, there was a similar crossover in the consumption of a wide range of cultural experiences.

Formerly, a strict code of cultural segregation had prescribed which entertainments it was appropriate for each class to attend. Elitist entertainment was concentrated on three revered institutions all concerned with the performing arts: the Opéra, the Comédie-Italienne and the Comédie-Française. At the bottom of the league was the fun of the fair. This hierarchy was reflected in the protocol for publicity, and advertisements for the three elite theatres took precedence on walls in prime sites. Mercier described this: âThe theatre bills observe among themselves a certain rank: those of the Opéra dominate the others; the fair spectacles are placed at the side out of respect for the great theatres.' Symbolically, in the years leading up to the Revolution the rise of popular entertainment was such that the crowd-pleasing shows beloved by the ordinary people were soon being advertised alongside their highbrow rivals, no longer marginalized but mainstream.

The protocol went beyond the appropriate siting of posters: fiercely restrictive state regulation also dictated what popular theatres were permitted to perform. One of Curtius's neighbours on the Boulevard du Temple was the theatrical impresario Jean Nicolet, who, like Curtius, had started out at the fair. Nicolet was banned from performing any play in five actsâthe classical form that was the prerogative of the Comédie-Française and the Opéra. The entertainments he staged had to be in three acts, and the players were banned from speaking in verse. But this was no bar to providing the people of Paris with a good night out. In a constantly changing and affordable programme Nicolet mixed acrobats and rope-dancers with ballet and music. Night after night he received packed houses.

âMusic noise and “filles” without end' was how Englishman Arthur Young described the shows of Paris in this neighbourhood, although it is hard to imagine the appeal of some of themâthe 1779 ballet entitled

The One-Eyed Crippled Lover

, for example. Across the board, from the grand spectacles of the opera to the bawdy, sensational and sentimental entertainments of the Boulevard du Temple, the shows of Paris in the reign of Louis XVI became justly famous. The Russian man of letters Nikolai Karamzin, in his travelogue of Paris, observed, âThe Englishman trumps in Parliament and the exchange, the German in his study and the Frenchman in the theatre.'

Though the commercial theatre was dogged by restrictions about form and content, Curtius's exhibitions were outside the jurisdiction of censorship. This gave him creative licence, and he was able to impart a daring frisson to the arrangement of his figures. The notorious and the noble could be displayed in scandalous proximity to one another, and for a small charge anyone who so desired could gawp and gossip to their heart's content. The waxworks were an audacious extension of the mixing-up of different sectors of society that was starting to happen in the world outside.

Culture vultures of every class sought new habitats. The biennial displays of paintings at the Louvre were phenomenally popular, with the general public descending in droves. This astonished an English visitor, and made him blush for his philistine countrymen: âI have often seen the lowest class of labourer with his two children and wife beside him stand before some fine picture explaining the part of scripture or history to which it referred and pointing out its beauties with all the taste of an artist.' While aesthete artisans appreciated the fine arts, with an element of social voyeurism well-to-do women braved the colourful crowds at the fair. Mrs Cradock, an English visitor, observed that âIt is good form to go to the fair,' and she was impressed by the calibre of some of the fairgoers. Similarly, it became common for aristocrats to abandon the elitist confines of the Opéra for the livelier shows in the popular theatresâthe theatres that, Mercier sagely observed, âeveryone claims to despise, and which everyone frequents.'

When they exchanged their usual patronage of highbrow entertainments for the lively pleasure dens frequented by the general

public, however, the beau monde liked to keep a low profile. Mercier noted, âSet in the fan which the pretty hand sways is a little round glass, through which my lady continues to see, unseen.' Some theatres went so far as to install grilles in boxes to satisfy their more aristocratic patrons' desire for anonymity. Private boxes were equipped with every comfort to make their occupants feel at home in unfamiliar surroundingsâthe statutory pair of pet spaniels, a foot-warmer, a chamber potâand a friend with a spyglass would survey the audience as much as the actors. Such was the boom in light entertainment that when the English equestrian showman Philip Astley was in town, also at the Boulevard du Temple, the smart set defected en masse from the opera and the ballet. While the grand cultural institutions were ghostly quiet, there was almost a stampede to see horses dancing minuets at the Amphithéâtre Anglais.

Cultural influence was starting to percolate from the bottom layers of society upward. Baron de Grimm noted, âThe populace has its pleasures that it madly loves, and the well-to-do who never have enough do not always scorn those of the people.' This was an understatement, for, far from scorning the pleasures of the people, the well-to-do could not get enough of them. They not only flocked to the fairs, but they were also mad for the full spectrum of boulevard entertainments that proliferated in this period and which were found in a dazzling concentration in the Boulevard du Temple and, from 1783, the Palais-Royalâboth sites where Curtius had prime locations.

The rise to prominence of the Temple district from the late 1770s onwards coincides with a falling away of support for the fairs. The more sophisticated brand of show business that appeared in the boulevard at this time filled the space between the bawdy banality of the fair and the starchy pretension of the elite cultural institutions. This new style of commercial entertainment perturbed the custodians of

Ancien Régime

culture, and they reacted by requiring commercial entertainers to pay fees to that stronghold of elite culture the Opéra. But it would take more than such taxes to quell the popularity of shows that were proving so ideally suited to the needs and interests of the growing ranks of prosperous self-made Parisians.

Through tapping into people's interest in the rich and famous, Curtius was fast becoming a wealthy celebrity himself. His Palais-Royal premises in particular were not only in tune with the times in appealing to all classes but were setting the pace. In an ultra-fashion-conscious society, the Salon de Cire was required viewing.

Freaks, Fakes and Frog-Eaters: An Education in Entertainment

A

S FOR THE

childhood and early life of Marie Grosholtz that incubated the character of the elderly woman we know as Madame Tussaud, we only have her word for what happened to her, filtered through Hervé in the 1838 memoir. It is from this single source that many of the most famous and enduring myths about Marie stem. Until she is named as the legatee of Curtius's estate in his will, she is overshadowed by him to the extent that, while his exhibition and talents are well documented in many sources, Marie Grosholtz is tantalizingly absent. A handful of legal documents, including his will, her marriage certificate, and assorted mortgage transactions, are the scant co-ordinates from which a very basic narrative of her life in France may be mapped.

The prominence of the original exhibition in the social landscape of pre-Revolutionary Paris meant that Marie grew up powerfully aware of the function the wax figures fulfilled in adjudicating fame. She grew up in a society where the seeds of the cult of celebrity were being sown, and Marie saw Curtius fêted for having created a perfect vehicle for exploiting this trend for personal profit. A precociously talented pupil, she quickly equalled him in modelling prowess and from an early age was contributing to the family business. Her youthful participation in the daily life of his various exhibitions was an apprenticeship that served her well. The art of wax modelling was just one of the skills he inculcated. He was an inspirational role model for entrepreneurial showmanship, and he deserves credit for the grounding he gave Marie in this, besides the material core of the exhibition that he passed on to her. He thus paved the way for Marie's success with her own version of the exhibition, which would in time eclipse the scope and renown of his original.

The currents of change in her early life made for a febrile atmosphere. As public opinion escaped from the shackles of officialdom during the reign of Louis XVI, tension escalated between official culture that was symbolically centred on Versailles and popular culture with a secular bias that was centred on Paris. Under the

Ancien Régime

, Church and state kept tight control of people's pleasures through a regime of suppression, censorship and vigilance. Certain information and ideas were treated like cultural contraband, confiscated from the public and impounded in the Bastille, although it was not only dangerous paper that was imprisoned: spells of incarceration or exile were almost badges of honour for Enlightenment writers. There were tight restrictions on the number of printers working in the city at any one time, and the majority of the most influential books in this period were published abroad. In a city where even a lost-dog poster required a signature from the lieutenant of police, Mercier wryly observed, âThere are in Paris only two documents which may be printed without leave from the police, the wedding invitation and the funeral card.' But, for all the attempts to control people's pleasures and to restrict their reading matter, restraint only made popular culture more lively, as Madame Campan sagely observed: âPublic opinion may be compared to an eel: the tighter one holds it the sooner it escapes.' The freeing of public opinion was the backcloth to Marie's life.

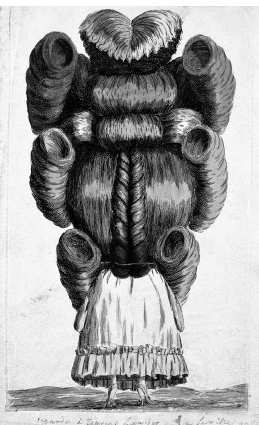

First as a vivacious little girl, then as a dependable and conscientious teenage assistant to Curtius, she saw him both monitor and profit from this trend. Growing up in the pre-Revolutionary period, she witnessed dramatic social change that gradually started to assume a political bent. In many respects Paris in the 1770s and '80s was like London in the 1960s: a heady mix of sex and shopping, with an anti-Establishment undercurrent. Beneath a shiny surface of fashion and frivolity a sense of social injustice was simmering. Marie witnessed the celebrity hairdresser and the fashion designer emerge as the new social heroes, and the clash between generations as the young kicked over the Establishment traces, rebelling with the height rather than the length of their hair. (Echoing every disgruntled parent, Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria, once wrote to her daughter Marie Antoinette, âI must touch on a subject that I hear mentioned on all sides. It is a question of your headgear. I have heard that it rises

thirty-six inches from the roots of the hair and it is built up in a tower with countless feathers and ribbons.') The young, including the Queen, also caused shock waves by rejecting hooped underskirts in favour of see-through loose-fitting clothesâa liberation that at the time represented as signal a protest as bra-burning. One of the âin' hairdressers, Beaulard, devised the perfect solution to following the new fashions without offending the oldies: a three-foot-high hair-do with a spring to adjust the height in an instant as soon as you encountered disapproving glares.

As a teenage girl Marie was probably familiar with Rose Bertin's famous boutique, La Grand Mogul, but she is unlikely to have been a customer. Although Curtius was wealthy, Bertin's creations were fabulously expensive and remained out of reach of all but a tiny seam of high society, of which the Queen was the most prestigious customer. With a business brain as sharp as her pins, Bertin came to be regarded as the most powerful woman in France, and was nicknamed Minister of Fashion. In her memoir Marie remembers Bertin as a âfirst-rate celebrity, and person of large property'. (She also relates that the great stylist lost her assets, and died in poverty in London. This is incorrect. Rose died in France, and was still supplying the courts of Europe with couture creations until shortly before her death.)

As the Ancien Régime lurched precariously from one public-relations disaster to the next (famously damaging was the Queen's association with the fraudulent purchase of a fabulously expensive diamond necklace in 1786), Marie observed at close quarters the establishment of a new form of absolute rule as the tyranny of fashion propelled Paris to a position of great power. Versailles bowed to Paris, as the ladies of the court obeyed every dictum from the hairdressers and stylists of the Rue Saint-Honoré. Growing up, Marie was barely more than a rolled-out bale of cloth away from the Rue Saint-Honoré, and, as we have seen, canny Curtius had commissioned fine clothes from Rose Bertin to enhance the feeling of authenticity of the costume of Marie Antoinette.

It was a society that treated serious subjects lightly, and light subjects seriously. Specifically, wars and the perilous state of the national economy inspired fashion accessories, hairstyles and light entertainment. For example, French involvement with the rebelling British colonies in America gave rise to a ballet themed on the conflict, and a hairstyle called

Les Insurgents

. There was also a commemorative hat with a warship in full sail to mark the naval battle of Belle Poule, and when the national coffers were empty, literally without funds, hats without crowns, â

sans fonds

', were fashionable, and named

à la Caisse d'Escompte

. In contrast, the length of a ruff and the cut of a coat were subjects of the utmost gravity. Appearances were taken even more seriously than behaviour, a blind eye was turned to vice,

but ridicule through inappropriate dress was social suicide, especially in court circles. These skewed priorities were reflected in the new fashion and lifestyle press that came into being at this time, with magazines such as

Galèries des Modes

and

Cabinet des Modes

being packed with tips on the latest looks for interior design and the textiles and prints to be seen in.

These priorities seem to have been adopted by Marie as well, for throughout her life she placed great emphasis on the details of dress (professionally, not personally), and her memoirs are most valuable for the amount of information about costume and uniforms, with barely any insights, analysis or opinions about the more serious issues of the day. Her descriptions are like entering a musty wardrobe. We get a vivid sense of the cut and cloth of famous historical persons' dress, but a less clear impression of the cut of their character. Typical of this approach is her account of Voltaire's appearance:

He wore a large flowing wig, like those which were the mode in the time of Louis the Fourteenth, was mostly dressed in a brown coat with gold lace at the button-holes and waistcoat the same, with large lappets reaching nearly to the knees and small clothes of cloth of a similar description, a little cocked hat and large shoes, with a flap covering the instep and generally striped silk stockings. He had a very long thin neck and when full dressed had ends to his neckcloth of rich lace, which hung down low as his waist; his ruffles were of the same material, and according to the fashion of the day he wore powder and a sword.

In sharp contrast was the âArmenian costume' of Rousseau, and the âblack corded velvet' favoured by Mirabeau.

Clothing reflected the heightened interest there was in the present. While leopards don't change their spots, people do, and when Louis XVI acquired a zebra stripes suddenly appeared on virtually every man of the moment, as recorded by Mercier: âCoats and waistcoats imitate the handsome creature's markings as closely as they can. Men of all ages have gone into stripes from head to foot even to their stockings.' More formative for Marie's future development was her witnessing the perpetual drive for novelty, with the public embracing and then rejecting one person and product after another. There was Parmentier, the agriculturalist, who inspired potatoes as a motif on

everything from fans to cambric cotton prints and wallpaper. The much fêted ambassador Benjamin Franklin, who with his beaver hat and homely dress endeared himself to the Parisians as a man of the people, became a one-man Franklin Mint, his likeness made in endless statuettes, engravings and busts. His celebrity status prompted him to write to his daughter, âThe numbers of medallions sold are incredible. Those with pictures, busts and prints of which copies are spread everywhere have made your father's face as well known as the moon, so that he durst not do anything that would oblige him to run away, as his phiz would discover him wherever he should venture to show it.' Madame Campan relates how the market for Franklin medals was so great and trade so brisk that âEven in the palace of Versailles, Franklin's medallion was sold under the King's eyes.' A few years later the gun-running dramatist Beaumarchais, in the wake of the phenomenal success of his Figaro plays, became not only wealthy, but the subject of commemorative merchandise. As an English visitor, Mrs Thrale, noted, âBeaumarchais possesses so entirely the favour of the public, that women wear fans with verses on them out of his comedy.' Even the charlatan mystic Cagliostro, before he was exposed in 1787, inspired a range of ribbonsâ

rubans à la Cagliostro

.

Importantly, young Marie absorbed in every fibre of her being the unifying trait that Mercier described as âthe love of the marvellous'. From the age of six until her late twenties, when a dramatic change of tempo affected the whole of France, Marie was at the heart of a city discovering how to have fun. The myriad entertainments that flourished at this time cemented the reputation of Paris as the capital of hedonism, and the Parisian propensity to play hard became regarded as a national characteristic. Observers from different countries were united in their appraisal of their fun-loving French counterparts. The Earl of Clarendon remarked, âIn England a man of common rank would condemn himself as extravagant and culpable if he permitted his family to partake of amusements more than once or twice a week. In France, all ranks give themselves up to pleasure indiscriminately every day.' The Russian traveller Karamzin concurred: âNot only the rich people who live only for pleasure and amusement, but even the poorest artisans, Savoyards and peddlers consider it a necessity to go to the theatre two or three times a week.' Gouverneur

Morris was struck by the indulgent lifestyle of the women in his circle. He paints a picture of the vacuous lifestyle of a lady of leisure: the few hours âwhen she is not being tended to by the coiffeur she is giving to spectacles [exhibitions]'.

One of the most striking descriptions of the pleasures of Paris, and the decadence of the inhabitants, as compared to wholesome America, was made by Thomas Jefferson in a letter to Mrs Bingham on 7 February 1787. He paints a picture of leisured ennui, a cycle of pleasure-seeking, which he contrasts to his homeland: âIn America, on the other hand, the society of your husband, the fond chores of the children, the arrangement of the house, the improvements of the grounds, fill every moment with a healthy and useful activity.' (As if even all that time ago they were a nation of Martha Stewarts!)

Mrs Thrale was surprised by the round-the-clock, seven-days-a-week availability of amusements. Entertainment was a commodity peddled in forms ranging from the small-scale peep shows that Savoyard girls strapped to their backs to the spectacular displays of equestrian showmanship by Astley and the Franconi brothers in a floodlit hippodrome with twelve hundred jets of flame and a full orchestra. It is little wonder that later on in life Marie stressed her royal patrons, for she had witnessed the impact of Marie Antoinette's patronage on Astley's show. Horace Walpole complained in London, âI shall not have even Astley. Her Majesty the Queen of France, who has as much taste as Caligula, has sent for the whole of the dramatis personae to Paris.' The King, a man miserable on the throne but happy on horseback, shared his wife's enthusiasm and was moved to present the equestrian stuntman with a token of appreciation in the form of a diamond-studded medal. Court interest in the people's pleasures is striking in this period. Axel von Fersen, the Queen's admirer and friend, described the Versailles passion for the shows of Paris as a mania. âWe miss none of them, and would prefer to go without drink, food and sleep than to ignore any spectacle.'