Kerry Girls (3 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

The major problems contributing to the devastation in Kenmare during the Great Famine stemmed in the main from its geographic isolation, its absentee landlord and the population explosion in subdivided land. The remoteness of Kenmare, the relatively small number of Protestant residents or officialdom, had contributed in the previous generation to a general disregard for the law. A ‘blind eye’ had been turned to the vigorous smuggling trade carried on in the area, and later middlemen, both Protestant and Catholic, had likewise ignored the stipulations in leases regarding the subdivision of landholdings. Communication by road was very difficult. As late as 1828, Kenmare to Derrynane was seven hazardous hours on horseback and, according to Daniel O’Connell, best approached by Killarney or by sea. Only in 1841 was the suspension bridge was erected over the Kenmare River, replacing a ferryman.

The Marquess of Lansdowne’s estate amounted to over 94,000 acres in county Kerry, mostly in the Kenmare area. This estate owes its origins to Sir William Petty. He was granted extensive lands in South Kerry, formerly the property of the O’Sullivans, in the seventeenth century. These extensive landholdings then passed through his daughter Anne Petty, who married Thomas Fitzmaurice, 1st Earl of Kerry, and then through their grandson, William Petty-Fitzmaurice.

23

In Kenmare, Lord Landsdowne’s estates had been badly but charitably run by his agent James Hickson for a number of years. He never took on the challenge of subdivision of holdings that was endemic in this area and which in a previous generation had been encouraged by the estate.

24

Hickson, as a result, was a popular agent and was well regarded by the tenantry. This lead to large numbers of families living virtually on top of each other, in cabins grouped together in miserable conditions. Fr John Sullivan of Kenmare told the Devon Commission that the condition of the population was ‘very wretched and debased’.

25

William Steurt Trench was appointed the new agent for the Landsdowne Estates in 1849. Having examined the records of the estate he was horrified by the daunting situation. At that time, of the 10,000 paupers then receiving relief in the Union, 3,000 were chargeable to the Landsdowne property. He calculated that maintaining them in the workhouse would cost the estate £5 per head per year when the valuation of the property was barely reaching £10,000 per year.

The living conditions contributed not only to even greater hunger when the potatoes got scarce but it also led to greater risk of disease spreading in this area. The medical officer’s report of 22 May 1847 detailed:

During the past two months the number of those suffering from fever, dysentery and measles averaged 220 per week and 153 inmates died during that period. The workhouse is not only a great hospital for which it was never intended or adapted, but an engine for producing disease and death, as a fearful proportion of the admitted in health fall victim of the fever in a few days due to the crowded state of the house.

26

Another custom which was peculiar to the area was the migratory habit that not only had the labourers travelling as

spailpíns

to neighbouring counties of Cork, Limerick and Tipperary, but entire families ‘nailed up the doors of their huts, took all their children along with them, together with a few tin cans and started on a migratory and piratical expedition over the counties of Kerry and Cork, trusting to their adroitness and good luck in begging to keep the family alive until the potatoes came in again’.

27

There was an element of proselytising also in the Kenmare area which was reflected in religious strife in the workhouse. In 1850 Denis Mahony of Dromore, who was a minister of the Church of Ireland, established a soup kitchen there and preached to the hungry who came to get some sustenance. This angered the local people, desperate for food. His church was attacked and some of the enraged group then set to uprooting flowerbeds and shrubs in the garden of Dromore House. According to local folklore, it was only through the intervention of Fr John Sullivan that they were stopped as they were about to set fire to the house.

While the degree of destitution in Killarney town was great compared to the other Unions in Kerry, the Killarney Board of Guardians functioned best in the Famine years. The main landowners, Lord Kenmare and Henry Arthur Herbert, were resident in the area and the Poor Law Guardians were responsible and committed.

Smith states that Sir Valentine Browne was granted over 6,000 acres in county Kerry after the Desmond Rebellion. Political allegiances in the seventeenth century caused the size of the estate to fluctuate. It was consolidated in the eighteenth century and the Kenmare estate amounted to over 91,000 acres in county Kerry in the 1870s.

28

By the time of the Famine, Lord Kenmare’s land was held predominantly by middlemen. In all his property in Kerry in 1850, the earl had only 300 direct tenants, a very small fraction of the total occupiers.

29

Between 1845 and 1850 Lord Kenmare was able to collect as much as £65,500 out of £93,430, 86 per cent of the rents due.

30

This was achieved without abatements to the middlemen, nor did they default heavily. Rather they squeezed their under-tenants which in turn led to greater poverty and distress among the smaller tenant farmers.

A good example of the subdivision on the Kenmare estates was given by John Leahy of Killarney, in evidence to the Devon Commission, and it clearly outlines the problems subdivision caused both for the tenant and the landlord. He quoted the case of a farm of 30 acres on the Muckross Estate:

The Lease was made about the year 1800; the rent was £10 Irish. It was let to one tenant but at the time of giving the evidence it had twelve families occupying it, with an average of six persons in each family, he estimated that there would now be seventy two persons living off it. ‘With such a mode of cultivation as there is in this country, this farm could hardly support the population on it.

Henry Arthur Herbert MP, was the other principal lessors of property in the Killarney Poor Law Union. In the 1870s his estate amounted to over 47,000 acres in county Kerry. The centre of this large estate was at Muckross, much of it now included in the Killarney National Park.

The Killarney Board of Guardians had funds and the necessary commercial capability to run the workhouses more efficiently than most. By 1850 they had eventually opened up to eleven auxiliary workhouses. The

Tralee Chronicle

of July 1848 quoted a Poor Law inspector who had visited Killarney Workhouse as saying, ‘if it was not the best in Ireland, then it was certainly one of the best’.

31

From the mid-eighteenth century, Killarney enjoyed a healthy tourist trade and by the time of the Famine international visitors to the town were even enjoying outlying tours of the Ring of Kerry. This trade no doubt helped the merchants of the town and in turn influenced the businesslike running and governance of the Poor Law Union.

Slater’s Directory

tells us that there were three hotels in the town by 1846. Slater also states of this time: ‘Only Killarney and Tralee were showing signs of prosperity.’

32

Even earlier than this the

Limerick Chronicle

reported, ‘Mr. Jackson, son of the President of America and Louis Napoleon Bonaparte are at the Lakes of Killarney.’

33

So while Killarney would seem, on the surface, one of the better off areas, this was not the entire story. The main landlords being resident in the area and a thriving tourism business masked the situation of the poor unemployed and uneducated in the lanes of the town. It masked the pressure on the cottier and smallholder from the middleman who must and will collect his rents no matter what.

Ellen Leary

Ellen Leary of Islandmore, Glenflesk was the daughter of Daniel Leary and Julia Healy. Ellen was born on 14 October 1832. Kerry baptismal records show that Ellen had at least one older brother, Denis (b. 1825), and younger siblings Ignatius (b. 1833), Gobnet (b. 1837) and Catherine (b. 1840).

Glenflesk incorporated the ancient parish of Killaha. The ruins of the original church, built around the twelfth century, still stand in the graveyard there and a new church built in 1801 continued in use until 1860. Glenflesk, like all other Kerry areas, suffered greatly during the Famine. The parish priest, Fr Jeremiah Falvey, died on 28 December 1846 as a result of caring for the sick and dying. Fr Falvey, who lived for some years at Curraglass in the house owned by Patrick O’Donoghue, was evicted by the landlord, Herbert of Muckross, due, it is said, to his having voted or having got the parishioners to vote against the latter. We are told that ‘Glenflesk is renowned for the number of priests born in the parish’,

34

and indeed Ellen’s brother Ignatius later became a priest.

Ellen, together with thirty-four other girls from Killarney Workhouse, travelled initially to Penrose Quay, Cork and from there to Plymouth to join the barque

Elgin,

which had started out from Liverpool initially, on its voyage to Port Adelaide.

Cheryl Ward, of Melbourne, takes up the story of what became of her ancestor:

The ship arrived at the McLaren Wharf, at Port Adelaide on September 10th, 1849. The wharf had only been completed a few weeks before their arrival but port conditions were still very basic. Ships anchored in the river and transferred their passengers and cargo in rowboats. The road to Adelaide was worse than a track and it often took 12 hours to travel the few miles into the city. A spring cart would make the journey for 20 shillings a head and a bullock dray was an alternative at 5 shillings a head but the dray was only marginally better than walking.

35

Ellen spent the next three years in South Australia.

36

No records have yet been located for her during this period.

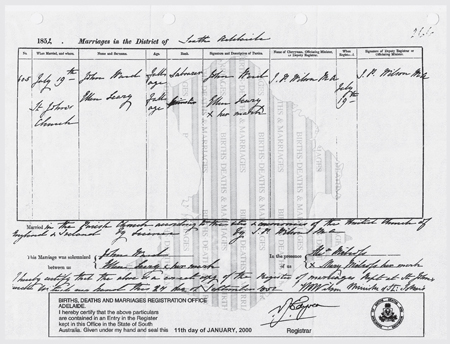

She met an Englishman, John Ward, on 19 July 1852 and was married to him by the Revd T.P. Wilson, Minister of St John’s Anglican Church, Adelaide. John Ward is described as a labourer. Ellen signed the register with an X.

Ellen and John are noted as being of ‘Full Age’ on the marriage certificate, but there are the usual age discrepancies. We know from Ellen’s baptismal certificate that she was 20 years of age when she married.

At some point after their marriage, between 1852 and 1855, the young couple made their way to Fryers Creek, State of Victoria, where large finds of alluvial gold had been reported in 1851 and it was here that the first of their nine children, John Charles, was born.

The marriage of Ellen Leary and John Ward, Adelaide, 19 July 1852.

During the gold rush people journeyed, sometimes over vast distances, to and from the diggings. Excited and filled with hope, they made their way to the goldfields by any means available. The trip was difficult, with no made roads to the diggings and crudely constructed river crossings, it could be hot, dry and dusty or wet, muddy and boggy.

Perhaps due to dwindling gold supplies in Fryers Creek, Ellen and John can next be found in Ballarat, where they settled for over a decade and where Ellen was to give birth to a child every second year from 1857 until 1869, with a respite period of four years(!) before their last son, Samuel Ignatius, was born in 1873.

The first evidence we have of Ellen and John in Bairnsdale is in 1885. In 1862 rail lines reached from Melbourne to Gippsland but the gold towns in this area never grew into large provincial cities like Ballarat; however, Bairnsdale was a solidly established gold town.

Ellen died suddenly in Bairnsdale in 1902 at the age of 67. She was survived by John, occupation now listed as grazier, and all but one of her children. Her estate included two allotments of land in the county of Dargo, one 60 acres including a five-roomed weatherboard house, the other 32 acres, as well as a bank account containing £74.

Curiously the assets were in Ellen’s name. John states in probate documents presented to the Supreme Court in 1902, ‘I transferred the said allotments as a gift to her and for which she obtained a Certificate of Title in her own name, in the month of May 1885’ and ‘… the money in the savings Bank at Bairnsdale is deposited in her own name and was the proceeds of presents or gifts from myself and her children’. The reason for this is still unclear.

John died ten years later, in 1912. They are buried together in Bairnsdale cemetery.

Absentee landlords and the middleman system were particularly prevalent in north Kerry. In the Barony of Iraghticonnor, 40,000 acres were owned by Trinity College but leased to middlemen. Other prominent landlords and agents in this area were Lord Listowel and Sir John Benn Walsh together with the Locke Estate (Lady Burghersh), who were all non-resident. Resident landlords and agents included the Crosbies, Stoughtons, Guns, Sandes, St John Blacker and Pierce Mahony, who were mostly in control of lesser lands.

In the 1824 minutes of the evidence put before a Select Committee on the Disturbances in Ireland, chaired by the Right Honourable Lord Viscount Palmerson, Dr John Church said: