Kerry Girls (4 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

I have known a farm that has been let perhaps thirty years ago to one tenant, to a single individual, and when it was out of lease, and came into possession of the landlord, I have known it to be covered over thick with population, and most of them paupers. It is a very puzzling thing to know what to do with the poor people in such cases.

37

Evictions in North Kerry contributed in no small way to the number dispossessed who had no option but to make their way to the workhouse in order to have a roof over their heads. In an article by Tim P. O’Neill on Famine evictions,

38

he mentions Kerry in a number of places. The article goes into great detail in relation to the law on evictions. He states, ‘551 families were cleared from the Trinity College Estates in Kerry, while 16 families were cleared from Commonage in Kerry and their houses levelled.’

Sir John Benn Walsh, who owned extensive estates in North Kerry as well as in Radnorshire in Wales, visited his Kerry properties regularly and kept a journal of his tours. He made an address to the British House of Commons on 7 February 1849, explaining his actions regarding his Listowel Estates, and on 8 September 1851, Benn Walsh stated:

My own estates have been very much weeded both of paupers and bad tenants. This has been accomplished by Matthew Gabbett (his agent), without evictions, bringing in the sheriff or any harsh measures. In fact, the paupers and the little cottiers cannot keep their holdings without the potato and for small sums of £1, £2, and £3 have given me possession in a great many cases when the cabin is immediately levelled. Then to induce the larger farmer to surrender their holdings when they become insolvent, I emigrated several, either with their whole families or in part.

39

We also have the evidence of Fr Matthias McMahon, parish priest of Ballybunion, who in an extensive letter to

The Nation

in August 1850 claimed:

The landlords here may be classed among the worst in Ireland, justice and humanity are alike forgotten by them. The most malignant fiend in hell could not evince more indifference for the sufferings of human beings … Numbers there are in this doomed district who at no distant period shall be pining in a workhouse, or starving, or wandering over their own land and all owing to the barbarity of the landlords.

40

Fr McMahon goes on to say in regard to the unjust land laws:

By a system of detestable injustices an incoming tenant will get abatement which if the former got he might hold on respectably. No matter how much of his labour and capital he may have sunk in the land he is cast out without a farthing compensation.

He calls attention in particular to the activities of St John Blacker, middleman in control of the vast acreage of Trinity College, whom he accuses of demolishing an entire village of twenty houses and ‘setting the inhabitants adrift’.

41

We get a very good description from the Listowel area of the actual conditions of fourth-class houses, as listed in the 1841 Census, then occupied by 60 per cent of the population of the county, from Johanna McKenna of Glashnanoon, Lyreacrompane who gave this account to the Schools Folklore Collection in 1937, when she was 78 years old:

No Slate houses then, no rooms in them – they had the bed in the kitchen. They used to call them ‘

botháns

’ and if the walls were made of mud as they used to be, they called them ‘

Bothán na follaicki

’. Sometimes they were made of black sods of bog and then they were called ‘

na bothán dubha

’ and if they were built on a hill, they call it ‘

mo bothainín dubh an conaic

’. Sometimes the fire was in the corner with a hole on top for a chimney. There was no glass in the windows. They had wire and board they called ‘shutters’. The floor was made of mud and they had no half doors. They used turf for fire and a candle for light. They had a board stuck on the wall and put the candle on that. They made the candle themselves.

A butter market was established in Listowel in 1845 and the ‘strong’ North Kerry farmers continued to send their produce to the Cork Butter Market right through the Famine. According to Charles O’Brien’s

Agricultural Survey of Kerry

,

in the early 1800s ‘Listowel was one of the five major grain centres in the county’

42

and this grain also continued to be exported for the duration of the Famine. According to John Mitchel, quoted by Cecil Woodham-Smith:

43

Ireland was actually producing sufficient food, wool and flax, to feed and clothe not nine but eighteen millions of people, yet a ship sailing into an Irish port during the famine years with a cargo of grain was sure to meet six ships sailing out with a similar cargo.

Some of this corn was shipped from Tralee.

So in 1845 we have our large extended impoverished families living in cabins, dependent on their patch of ground to produce enough potatoes to give them three meals a day washed down with buttermilk, sleeping on straw on the bare earth without any work available to the vast majority. We have depended on folklore to tell us that this section of the Kerry population were ‘poor but happy’. They understood well that their options of improving their lot were very limited, and led a day-to-day existence. They placed great emphasis on song and dance, on storytelling, and had close relationships with their neighbours and parish. They valued strong ties with their extended families and depended on them for practical and emotional support. They were not lazy, stupid, promiscuous or immoral as they were portrayed in the British media.

We also have a smaller number of ‘strong farmers’ investing their time, energy and whatever finances are available, working their acreage, improving their living conditions and agricultural holdings, educating their children and reasonably content that their families are aspiring to a better class of life.

Thus were the conditions in Kerry when the potato blight first struck in the autumn of 1845.

Bridget Ryan

Bridget (Biddy) Ryan is one of the intriguing stories of the Earl Grey Orphans’ and one we have not solved entirely. When Bridget was originally ‘selected’ by Lieutenant Henry in Listowel Workhouse, her address on the Minutes on 11 September 1849 was ‘Listowel’. However, when she arrived in Sydney on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

on 3 February, she declared her native place as Bruff, Limerick, gave her age as 16, her parents as Anthony and Johanna, and stated that her father (a soldier) was living in Sydney. She was able to read and write. It was noted under ‘State of Health, strength and probable usefulness: Poor’.

Bridget’s great-great-granddaughters – Julie Evans and Jeanette Greenway have done extensive work to uncover Bridget’s family in Ireland and also have provided us with a record of her life in Australia:

Bridget’s first employer was a Captain Mac Kellar who was a Master Mariner and originally from Elgin in Scotland. It is not clear how Bridget met her husband James Murray and it may have been through this employer.

James had arrived from Scotland in 1848. Family lore suggests he was working in Sydney at the time, though his brothers were farming in the Manning River area of New South Wales. Bridget and James were married in Sydney in December 1850 and in December 1851 they had the first of their thirteen children (one did not survive infancy). It has been impossible to trace the Australian marriage certificate of James and Bridget and other dated information we have has been obtained from their death certificates.

Roman Catholic Bridget became a Free Presbyterian on her marriage and is reported to have adopted her new faith with great vigour. They were reported as being ‘pillars’ of their Church and James was a churchwarden for many years.

James and Bridget set up their first home on a farm at Mondrook. After severe floods for three years in a row, they moved to a dairy farm on Oxley Island where they remained until James died in 1893. There are ruined and overgrown remains of the old dairy still on this property but the house is long gone.

The children were brought up strictly in the Presbyterian faith. Four of James and Bridget’s children married their cousins, as was common at the time. All their children remained in New South Wales. Descendants of these children have now scattered widely across Australia and overseas.

It is said that when James died in 1893, his casket was brought down the river on a steam tug and taken to Tinonee for the funeral service. James was buried in Tinonee Cemetery. Bridget died in 1909 and was buried beside James.

While Bridget’s life in Australia is well documented, it is her history in Ireland that is most intriguing. Thanks to Julie and Jeanette we get a partial and tantalising glimpse to her background in Ireland. This background is the subject of a TG4 Documentary to be shown in October 2013.

From the initial snippets on record that Bridget’s father was in Sydney and was a soldier and from her Australian family folklore that she herself had been educated in Ireland by ‘French nuns’, we pieced together her background as it was in 1849 when she left Listowel Workhouse.

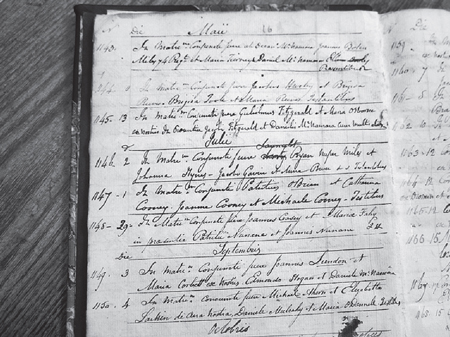

The marriage certificate of Johanna Hynes and Lancelot Ryan, Bruff parish church 1831.

Bridget’s parents were Johanna Hynes and Lancelot ‘Lanty’ Ryan (not Anthony). Johanna and Lancelot, as he was called on the marriage certificate, were married in Bruff Parish Church on 2 July 1831. Written in Latin, his occupation was given as ‘lately a Soldier’.

Searches for Lanty’s career as a soldier in Australia didn’t realise any results and it transpired that the reality was somewhat different. He had in fact got married again, bigamously, in 1837 in Abbeyfeale, County Limerick and as a result he had been transported as a convict to Australia. The following is an extract from the New South Wales State Records:

Convict List for the Ship Neptune 1837-1838

The vessel departed Dublin 27 August 1837 for the 128 day voyage to Sydney. The prisoner list includes:

Ryan Launcelot, age 35, tried 1837, Limerick 7 yrs, b. 1803 Tipperary, bigamy, married, 1m 1f children, soldier labourer, blind of left eye, CF 44/1140

Lanty tried to make a deal just before the

Neptune

sailed out from Kingstown Harbour in Dublin. He had some involvement or knowledge of an incident in 1831 during the Tithe War in Doon, Co. Limerick, where a number of men had attacked the Rev Charles Coote who was endeavouring to collect the hated Tithes, then due to the Established Church of Ireland by all landholders, most of whom would have been Catholics. A reward was offered for information on the culprits and while Lanty had not made any claim to the money for the previous six years, he now tried to use his information in a last ditch effort to escape transportation. It was too late however, and the ship sailed.

On arrival in Australia, he was noted as having a number of facial injuries, scars, one eye and one arm and as such was of no use as a convict worker in the bush. He seems to have remained in the special compound in Port Maquarie for old, infirm or disabled convicts and it is most unlikely that Bridget ever met him.

Bridget Ryan Murray in old age.

Waterview House, Balmain, where Bridget Ryan worked. According to her descendent, Julie Evans, ‘the house was leased by the man who employed Bridget in 1850’. (Courtesy of State Library of NSW)

Even after extensive research, we have no idea what happened to Johanna or her family in Ireland. Johanna, on the conviction of her husband, would have had only two options open to her – to return to her own family home in Bruff or to seek shelter in one of the workhouses, then in Kilmallock and Limerick. We have to presume that she went back to her family near Lough Gur, and it would appear from Bridget’s own story to her children that she herself spent some time as a pupil in Laurel Hill Convent in Limerick, then the only convent with ‘French nuns’. This is quite possible as the famous Dean Cussen was then the parish priest of Bruff. He was one of the principal supporters of the sisters in Laurel Hill, who had just opened their school (in 1845) and he may have arranged through the Hynes family (Bridget’s grandparents) that Bridget be taken in there.

So how did Bridget, a native of Bruff, end up in the workhouse in Listowel? This is another mystery that probably will not be solved now, 160 years later. According the rules governing the Earl Grey Scheme, ‘orphans’ to be selected should have been resident in the workhouse for at least one year. My own sense is that a benefactor used his influence with the Board of Guardians to get her away from the wretched circumstances, the poverty and despair that would have been her fate in Ireland. This benefactor may have been Dean Cussen once again.