Kierkegaard (21 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

In the main Søren's writing energy was spent on his journals, which

by this time were plainly intended for (eventual) publication after his death. An “Open Letter” to one Dr. Rudelbach published in the

Fatherland

on the last day of the year 1851 represents Søren's only foray into the public cut-and-thrust during this period. It is a telling indication of Søren's position at this time. Andreas Gottlob Rudelbach was a renegade reformer who tried to enlist Søren in his schemes to bring about the political separation of church and state. Rudelbach had thought that as a fellow critic of “

habitual Christianity

,” Søren would be a worthy ally to his cause. In his letter, Søren readily agrees, “I am a hater of âhabitual Christianity.' This is true. I hate habitual Christianity in whatever form it appears.” However:

Habitual Christianity can indeed have many forms . . . if there were no other choice, if the choice were only between the sort of habitual Christianity which is a secular-minded thoughtlessness that nonchalantly goes on living in the illusion of being Christian, perhaps without ever having any impression of Christianity, and the kind of habitual Christianity which is found in the sects, the enthusiasts, the super-orthodox, the schismaticsâif worse comes to worst, I would choose the first. The first kind has still taken Christianity in vain only in a thoughtless and negative way. . . . The second kind has taken Christianity in vain perhaps out of spiritual pride. . . . One could almost be tempted to smile at the first kind, because there is hope; the second makes one shudder.

Søren has harsh words for the obsession with political solutions to spiritual problems that he perceives in Rudelbach and other enthusiasts:

There is nothing

about which I have greater misgivings than all that even slightly tastes of this disastrous confusion of politics and Christianity. . . . If this faith in the saving power of politically achieved free institutions belongs to true Christianity, then I am

no Christian, or even worse, I am a regular child of Satan, because, frankly, I am indeed suspicious of these politically achieved free institutions, especially of their saving, renewing power.

He ends his letter with a reiteration of his life's task. “

I have worked

to make this teaching more and more the truth in âthe single individual.' . . . I have aimed polemically throughout this whole undertaking at âthe crowd,' . . . also at the besetting sin of our time, self-appointed reformation.”

Any reform Søren wanted was inward, not external. Another short book,

For Self Examination

drove the point home when it was published on September 10, 1851, under his own name. The so-called “silent years” follow the publication of this book. Over three years in which Søren, astonishingly for him, does not print a thing.

Judge for Yourself!

was written at this time but not published, as Søren judged for himself that the time was not right to so openly pursue its theme (more stringent than in

Practice

) of reintroducing Christianity into Christendom. A myriad of journal entries during the silent years reveal that Søren was honing his material. A long entry entitled “About Her” recounts the frequent street meetings (including a smile from

Regine

on his birthday: “Ah, how much she has come to mean to me!”) and a significant event at a church service where the text was once again James 1:17. Before the preacher began his sermon, Søren (who was sitting behind) records that Regine impulsively turned her head to look at him before sinking down in her seat. Søren saw the sermon and the event as a sort of release for them both.

Besides repeated returns to Regine, the Single Individual, and “his task,” multiple other entries consider Mynster and Søren's relationship to him. One long entry from 1852 entitled “

The Possible Collision

with Mynster” is typical insofar as it sketches ways and means for Søren to take the fight further. “My position is: I represent a more authentic conception of Christianity than does Mynster. . . . A little admission from his side, and everything will be as advantageous as possible for him.”

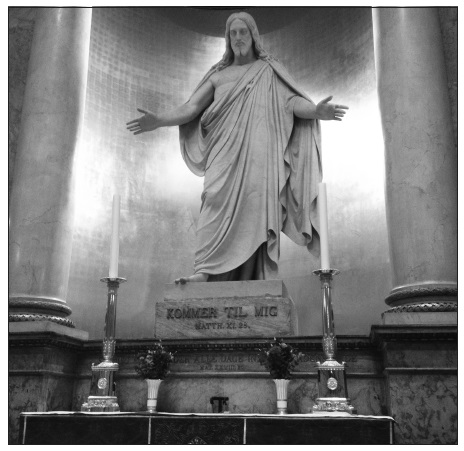

Christus

by Bertel Thorvaldsen. The statue is located at the front of Copenhagen's Church of Our Lady. It bears the inscription from Matthew 11:28: “Come to Me.” The statue and its invitation are key elements of Søren's book

Practice in Christianity

, which was meant as a wake-up call to Mynster and the Danish Church.

The plans were all for naught, and Søren would never see the bishop converted to his cause. Mynster died on January 30, 1854. His memorial service was not light on pomp and circumstance. Denmark's finest were out in force, with priests from across the land arriving early in the day to be a part of the proceedings. Martensen, as the royal court chaplain, presided over all. Due to deft manoeuvring on Martensen's part, the gap between Martensen and Mynster had considerably narrowed over

the years. Now it was well known that Martensen, although relatively young, had realistic aspirations to be Mynster's successor. As such, his memorial sermon was not without some regard to his own position. Whatever he said about Mynster as bishop was alsoâwhisper itâwhat Martensen envisioned for himself. So it was that in the memorial address Martensen held forth:

So let us now

then imitate his faith . . . that his memory amongst us in truth must be for upbuilding! Let us admonish ourselves as we say: Imitate the faith of the true witness, the faith of the authentic witness to the truth! . . . [let his precious memory] guide our thoughts back to the whole line of witnesses to the truth, which is like a holy chain stretching itself through the ages from the day of the Apostles until our own day.

One can only imagine Søren's immediate reaction to hearing this speech using his favourite terms like “upbuilding,” “apostle,” “authentic,” and, especially “truth witness.”

Of

Mynster, of all people,

by

Martensen, of all people.

Søren vibrates angrily in his pew. He goes home. He writes a scathing response. He leaves it in his desk. And he bides his time.

A Life Concluded

The visitor is perched on an armchair in the sitting room waiting to be called in to Sunday lunch. Anna is in the corridor outside. “

I have so little desire

to be at the table today,” she whispers to her husband, Henrik. “Do you think I can stay away?”

Henrik sadly shakes his head. Duty demands. They both arrange their smiles and bring their guest to the table. “Søren!” Henrik calls out with desperate bonhomie, “Can I tempt you with a little glass of Madeira today?” Anna flutters about, talking about the weather, her children, the servants. Anything at all.

The attempts at deflection fail utterly. Søren will not be put off his course. Immediately he launches into his favourite topic. What do they think about the old Bishop Mynster, now two months dead? Was he

really

a witness? A witness to

the truth

?

“Oh, Søren, let's not go into that old dispute,” says Anna. “We are totally familiar with one another's opinions, and to discuss it further can of course only lead to a quarrel.”

She should know. Søren has been a guest at their house now every day for a week. And every day the topic is the same.

Søren begins to gesticulate with his fork. He raises his voice. His comments become more pointed. He considers Anna to be a wise person and he respects her sound judgement. He wants to know, was Jakob Mynster a Christian or a poisonous plant? But there is silence. Anna, finally, has had enough. “You know the man of whom you speak so ill is someone for whom we cherish the greatest respect and to whom

we are profoundly grateful. I cannot put up with hearing him scorned unceasingly here.” Anna stands up, collecting her skirts. “Since you will not stop it, I can escape from it only by leaving the room.”

During the “silent years” from September 10, 1851, until December 18, 1854, Denmark's most prodigious prose poet published nothing. “Silence” however, is relative, for Søren never actually stopped writing or talking.

The story of Henrik and Anna comes from their son, Troels Lund. It was Troels' opinion that Søren was trying out his ideas about Mynster on normal people like Henrik and Anna. It is a credible theory. Søren, no stranger to street experiments and performance art, was yet again testing the limits of his audience. If Søren was wondering how upright citizens would react to an unconscionable attack on the memory of the deceased, then he got a clue from his friends. If the good people of Christendom were anything like the Lunds, they would be utterly confused, annoyed, and offended.

Søren's journals during these years see him working out his relationship to himself, to Regine, to Christendom, and to Mynster. The pages return again and again to these familiar topics, with Søren testing out new ways to understand and describe “his task.” He is biding his time and gathering his resourcesâbut for what? Books such as

For Self Examination

,

Sickness unto Death

, and

Practice in Christianity

were barely disguised attacks on the modes of life, thoughts, and beliefs that fell under the banner “Christendom.” Yet Søren repeatedly insisted to himself and others that his attack was, in fact, a defence.

Practice

had a “Moral,” calling the leaders of the church to admit their failing and fall on God's mercy for obfuscating real Christianity. The Moral was the mitigating factor, as Søren told Mynster directly in conversation. He tried to convince Mynster that his writings were intended to support the bishop and his church the only way that it could beâby starting anew

after admitting it had failed. Unsurprisingly, Mynster did not feel the need to submit to the entreaties of the upstart son of a former hosier. Needless to say, his admission of his church's guilt was not forthcoming. Søren's silence was due in large part to Mynster's silence. He was waiting for the bishop to act. The longer this did not happen, the more we see Søren's journals sharpen ideas and develop themes that had been long in gestation.

For one thing, Mynster is found, finally, to be powerless. So it is that by March 1, 1854, two months after Mynster's funeral, Søren is ready to write:

Now he is dead

. If he could have been prevailed upon to conclude his life with the confession to Christianity that what he has represented actually was not Christianity but an appeasement, it would have been exceedingly desirable, for he carried a whole age. That is why the possibility of this confession had to be kept open to the end, yes, to the very end, in case he should make it on his death bed. . . . Something he frequently said in our conversations, although not directed at me, was very significant: It does not depend on who has the most power but on who can stick it out the longest.

For another, Søren's long-held antipathy to Christendom hardens during the silent years, as does his conviction that it is now beyond redemption. Ultimately, it is the

Christendom

over which Mynster and his successors preside that is the issue, more than any one priest. The official relationship of state and church, whereby clergymen were effectively civil servants of the country and agents of civilisation is clearly a problem for Kierkegaard:

A modern clergyman

[is] an active, adroit, quick person who knows how to introduce a little Christianity very mildly, attractively, and in beautiful language, etc.âbut as mildly as possible. In the New

Testament Christianity is the deepest wound that can be dealt to a man, designed to collide with everything on the most appalling scaleâand now the clergyman is perfectly trained to introduce Christianity in such a way that it means nothing; and when he can do it perfectly, he is a paragon like Mynster. How disgusting!

Yet “Christendom” does not begin and end with the established church. In short, the “established church” might well be Christendom, but not all “Christendoms” are established churches. Christendom is a way of being, thinking, and feeling that has far more to do with the cultural appropriation of Christianity than it does with any specific legal agreement between church and state. Christendom is what happens when people presume they are Christians as a matter of inherited tradition, as a matter of nationality, or because they agree with a number of commonsense propositions and Christianised moral guidelines. Kierkegaard sees Christendom as a process by which groups adopt, absorb, and neuter Christianity into oblivion, all the while assuming they are still Christian. Christendom is adept at shielding itself from its own source, for Christianity's original documents offer a deep challenge precisely to the form of civilised life that Christendom represents.

The matter is quite simple

. The New Testament is very easy to understand. But we human beings are really a bunch of scheming swindlers; we pretend to be unable to understand it because we understand very well that the minute we understand we are obliged to act accordingly at once. But in order to make it up to the New Testament a little, lest it become angry with us and find us altogether wrong, we flatter it, tell it that it is so tremendously profound, so wonderfully beautiful, so unfathomably sublime, and all that, somewhat as a little child pretends it cannot understand what has been commanded and then is cunning enough to flatter Papa. Therefore we humans pretend to be unable to understand the N.T.; we do not want to understand it.

Here Christian scholarship has its place. Christian scholarship is the human race's prodigious invention to defend itself against the N.T., to ensure that one can continue to be a Christian without letting the N.T. come too close. . . . I open the N.T. and read: “If you want to be perfect, then sell all your goods and give to the poor and come and follow me.” Good God, all the capitalists, the officeholders, and the pensioners, the whole race no less, would be almost beggars: we would be sunk if it were not for . . . scholarship!

During this time, Søren begins to sound out medicinal, frequently gastroenterological, ways of talking about the situation. An 1854 entry reads simply: “

Christianity in repose

, stagnant Christianity, creates an obstruction, and this formidable obstruction is the sickness of Christendom.”

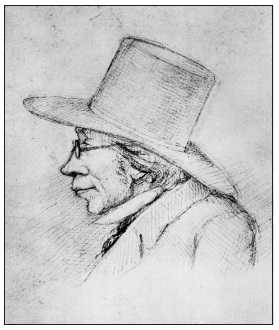

Søren Kierkegaard. Artist and wood engraver Hans Peter Hansen drew this likeness in 1854. Søren was unaware that he was being sketched at the time.

Fatal sickness requires radical cure. So it is that during the silent years, Søren's own self-identity as an author, too, undergoes development. He weighs his own communication style and finds it wanting. Up until 1851, Søren would confidently describe himself along poetic lines. His preface to

Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays

(August 1851) stipulated clearly that he was

not

a witness to the truth, he was

without authority

, and he was

not

claiming to say anything new that the New Testament has not already made clear. What Søren was, however, was “

an unusual kind of poet

.” Now, during this time of waiting and abiding the poet language begins to fall by the wayside. He had long realised that Christendom, with its emphasis on culture, rhetoric, and respectability had become more “art” than “religion.” “

All modern Christendom

is a shifting of the essentially Christian back into the aesthetic.” The last thing it needed was more people waxing lyrical. Søren never fully abandons poet language, but he does begin to question its worth and suggest alternative solutions to the problem of Christendom. Significantly, “

corrective

” language, present since 1849, comes to the fore. Correctives, by necessity, are sharp, effective, and one-sided. Poets are diffuse, subtle, languorous. Poets have all the time in the world. Correctives have to actâ

now!

âif they are to be of any use. “

After all

, the essentially Christian thing to do is not to write but to exist.”

Once again, ironically, Søren's sense of urgent, decisive action appears more in his diary than it does in reality. A new manuscript,

Judge for Yourself!

, was completed. The book pulls no punches, but its author did, and the draft was not sent to the publisher. Instead

,

Søren continued to practice his attacks on his uncomprehending friends. He sharpened his polemics in the privacy of his journals. He wrote a stinging rejoinder to Martensen's sermon a mere few days after Mynster's funeral but the fateful letter was not sent to the newspapers until almost a full year later.

Apart from Søren's habitual prevarication, which accompanied almost every decisive action of his life, an external reason for the delay was political. Bishop Martensen was formally consecrated as Mynster's successor on

Pentecost Sunday, April 1854. (Søren's journal does not disappoint: “

you can be sure

that there will be a lot of rhetoric about âthe Spirit'âhow nauseating, how revolting, when the true situation is that there is not a single one of us who dares pray for the Holy Spirit in earnest.”) The happy occasion was marked by fierce political in-fighting. The deeply conservative Prime Minister Ãrsted wanted Martensen as Bishop of all Denmark. The National-Liberal opposition did not. Søren kept his powder dry during this time, as he did not want his attack on Christendom

via

Mynster

via

Martensen to be associated with the party politics of either the left or the right. The partisan fight waged on for months even after Martensen's installation and contributed to the sitting government's instability. When Ãrsted was ousted on December 12, the liberals gained power, bringing with them, amongst other things, a more relaxed attitude towards public libel. The time seemed right to make a move.