Kierkegaard (9 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

I have just now come from a gathering

where I was the life and soul of the party; witticisms flowed out of my mouth; everybody laughed, admired meâbut I left, yes, the dash ought to be as long as the radii of the earth's orbitââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââand wanted to shoot myself.

The public could see the comparison between Søren and his brother Peter, his relationship with his father, his spending habits, odd ways, desultory studies, sharp wit, polemical manner, impressive friends. They saw a cocky young gentleman with little practical sense, too much spare time, too much money, and a lot of unfocused talent. And they saw rightly. What no one could know, however, was that Søren saw it too.

Søren began keeping a journal in 1833 and would continue to fill pages of volumes until his death in 1855. It is not a conventional diary by any means and rarely mentions the sort of daily events that other people tend to include in their log books. Most of the journal entries are undated. Some read like rough drafts of essays or written psychological experiments tracing the implications of this or that supposition. Some entries are rough-and-ready fragments; others are carefully edited with the full realisation that they would one day be read by others. The tone of the entries from the early stage of Søren's life are introspective, demonstrating a high level of self-awareness and insight into what is going on around him. His role of the arch-observer who participates in sophisticated society at the same time as he winkles out that society's weaknesses was one Søren recognised but did not relish. His journals reveal a growing distaste at events and of the part he was playing in them.

“

Blast it all

, I can abstract from everything but not from myself; I cannot even forget myself when I sleep.”

In the 1830s Søren was using the journals to test out different parts for himself, some of which he was to play for the rest of his life. One such role is that of “the master thief.” These early entries see Søren working on the theme of a rebel outsider who takes on the system and suffers punishment as a result. The journals are not all doom and gloom, even when they are morbid. Like the soldier in the trench or the nurse on the ward, Søren, the “master thief” awaiting his punishment, was adept at gallows humour. “

One who walked

along contemplating suicide,” he wrote in 1836, “at that very moment a stone fell down and killed him, and he ended with the words: Praise the Lord!” Or in 1837: “

Situation

: A person wants to write a novel in which one of the characters goes insane; during the process of composition he himself gradually goes insane and ends it in the first person.” Søren is alert to the ridiculousness of his own ennui: “

I don't feel like doing anything

. I don't feel like walkingâit is tiring; I don't feel like lying down, for either I would lie a long time, and I don't feel like doing that, or I would get up right away, and I don't feel like that either . . . I do not feel like writing what I have written here, and I do not feel like erasing it.”

The restless spirit accompanying the apparently carefree gadabout had in fact been awakened in 1835. Father Michael was concerned and flummoxed about his wayward son. That year, in order to get Søren away from the deathly atmosphere at home and the witty time-wasters of his Copenhagen circle, Michael paid for Søren to spend the summer well out of town. In June, Søren travelled to Gilleleje in North Zealand, the area from which the Kierkegaard family hailed. For the twenty-two-year-old urbanite, the time of country living in the fresh air was a revelation. If Michael had been hoping to occasion in Søren a sense of perspective, it is likely he never knew how successful his scheme had been. Outwardly and in public Søren would appear to continue with his dilettante life for years to come. Inwardly, however, the journals from Gilleleje suggest

serious work had begun. The entry for August 1, 1835, has become particularly famous. Its theme is about knowing oneself and one's way in the world and it deserves quoting at length:

What I really need

is to get clear about what I am to do. . . . What matters is to find my purpose, to see what it really is that God wills that I shall do; the crucial thing is to find a truth that is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die. Of what use would it be to me to discover a so-called objective truth, to work through the philosophical systems so that I could, if asked, make critical judgments about them, could point out the fallacies in each system; of what use would it be to me to be able to develop a theory of the state, getting details from various sources and combining them into a whole, and constructing a world I did not live in but merely held up for others to see; of what use would it be to me to be able to formulate the meaning of Christianity, to be able to explain many specific pointsâif it had no deeper meaning for me and for my life? . . . [Truth] must come alive in me, and this is what I now recognize as the most important of all. This is what my soul thirsts for as the African deserts thirst for water. This is what is lacking, and this is why I am like a man who has collected furniture, rented an apartment, but as yet has not found the beloved to share life's ups and downs with him. But in order to find that ideaâor, to put it more correctlyâto find myself, it does no good to plunge still farther into the world. That was just what I did before. . . . I have vainly sought an anchor in the boundless sea of pleasure as well as in the depths of knowledge. I have felt the almost irresistible power with which one pleasure reaches a hand to the next; I have felt the counterfeit enthusiasm it is capable of producing. I have also felt the boredom, the shattering, which follows on its heels. I have tasted the fruits of the tree of knowledge and time and again have delighted in their savouriness. . . . Thus I am again standing at the point where I

must begin again in another way. I shall now calmly attempt to look at myself and begin to initiate inner action; for only thus will I be able, like a child calling itself “I” in its first consciously undertaken act, be able to call myself “I” in a profounder sense. But that takes stamina, and it is not possible to harvest immediately what one has sown. . . . I will hurry along the path I have found and shout to everyone I meet: Do not look back as Lot's wife did, but remember that we are struggling up a hill.

Søren's quest for truth that was personally engagingâfor which he could “live and die”âled to an early rejection of much of the Christianity he had so far encountered. In an 1835 letter to his brother-in-law, Søren admits, “

I grew up in orthodoxy

, so to speak,” however, “as soon as I began to think for myself the enormous colossus gradually began to totter.” This was, undoubtedly, an awkward position to be in for someone training to be a minister in the established state church. Søren's prevarication did not spring from hostility to Christianity as much as aversion to the way Christianity took the form of coteries in Christendom. Brother Peter seemed to be able to align his religious seriousness with a willingness to associate with specific factions in church politics. For some years Peter had been a supporter of N. S. F. Grundtvig, a Danish nationalist, poet, populist politician, and church reformer whose group set Creedal Christianity against the liberal Christianity of Mynster

and

Bible-minded enthusiasts like the Moravians, who in turn were set against the cultured elitism represented by Martensen and Heiberg. The endless, noisy tribalism of Christendom was wearing on Søren. He did not mean to find his life's purpose by joining a

group

. Søren often writes of the enthusiasm to band together and defend a certain expression of Christianity as a type of betrayal of the original ideal.

Christianity was an impressive figure

when it stepped forcefully into the world expressing itself, but from the moment it sought to stake

out boundaries through a pope or to hit the people over the head with the Bible or lately the Apostle's Creed, it resembled an old man who believes that he has lived long enough in the world and wants to wind things up.

The coteries of Christendom did not seem to be good news for Christianity, or for individual Christians either.

When I look at a goodly number

of particular instances of the Christian life, it seems to me that Christianity, instead of pouring out strength upon themâyes, in fact, in contrast to paganismâsuch individuals are robbed of their manhood by Christianity and are now like the gelding compared to the stallion.

Unbeknownst to others, at the same time that Søren was accruing debt, waging snarky student politics, and climbing social ladders, he was also busy working out his relation to Christianity. It was increasingly becoming something that Søren knew he had to make a personal choice about. As a result, Søren became fascinated with the forms of life on offer for people who reject Christianity. His private writing from this time is filled with reflections on three legendary figures. Don Juan, Faust, and Ahasuerus the Wandering Jew represented, for Søren, different modes of life outside of religion. Søren primarily met the figure of Don Juan through repeated attendance of Mozart's

Don Giovani

at the Royal Theatre. Don Juan was a serial seducer and hedonist. He lives the immediate life of sensuality. Faust was singleminded and monogamous in his pursuit of knowledge and power. He is a doubter who delves into deep secrets for selfish ends. Ahasuerus is supposed to have mocked Jesus on the way to the cross and as a result was cursed to wander the earth undying until Jesus should return. In Søren's mind, the three exhibited ascending stages of rejection of Jesus Christ, culminating in Ahasuerus whose rejection was conscious and mocking. He represents the pinnacle

of despair because only he recognises how deeply personal the relation to Christianity is.

Søren clearly intended that his reflections on these three figures would form the basis for his first proper publication, the book that would put him on the map as a serious writer. He had been working over the material for years. Sadly, Søren's musings would remain largely confined to his private papers. He had been pipped to the post. In 1837, in one of Heiberg's edited journals there appeared a significant new essay by his despised tutor: “

Oh how unhappy I am

âMartensen has written an essay on . . .

Faust

”!

Never mind. There would soon be more subjects to occupy the young man's attention. For, over coffee at a friend's house one chilly morning in May 1837, Søren Kierkegaard met Regine Olsen.

Love Life

It is 1837. May 8. Mid-morning. Early spring and the chill is still in the air. As he often does, Søren drops by unannounced for a visit to his friend Peter Rørdam. Peter is a family friend and a fellow teacher at the School for Civic Virtue, but in fact it is Peter's sister Bolette who is the main reason for this visit. At twenty-one years of age and from a comparable family, Bolette seems a natural prospect for the twenty-four-year-old Søren to marry. However, it is not romance that is on his mind this morning. The polemical spirit and witty atmosphere in which Søren operates has been getting to him lately. Søren has been worried that sharp retorts and arguments are becoming a habit. He lives too much in his head and he knows it. Can he even converse normally anymore? Today, Søren is simply looking for real conversations with real people. In Bolette, Søren hopes to find someone to help get “

the devil of my wit

to stay home.”

When Søren arrives at the Rørdam house he finds a party of young ladies already there. His plan for simple interaction seems to be fading fast, and in any case it's too cold to be out walking with Bolette. Søren agrees to join the girls over coffee in the sitting room, and it is here that he meets Regine Olsen. She is fifteen years old, intelligent, composed, strikingly pretty. Søren does not mention her by name in his journal that night, but he does note the occasion and will later describe her effect over him as akin to a magic spell. Søren is smitten. Out of nervousness, a desire to impress, or perhaps simply muscle memory derived from habitual use, he reverts back to his witty ways. His words pour forth unceasingly, he overtakes the conversation and impresses everyone.

Regine does not show it at the time, but she will one day describe her young self as extremely

captivated

.

Later that night and in the days to follow, Søren reflects on the event. Even though he had originally gone to the Rørdams' as a way to escape rhetoric, he does not now berate himself for dazzling the party with his words. As with much in life, Søren begins to see that his curse can also be a blessing of sorts. As much as he recognises his predilection for witticism to be troublesome, in this instance it has protected him from something more dangerous. Writing about the day, Søren thanks God for not letting him lose his mind. The devil wit now becomes an “

angel with the flaming sword

,” and he is thankful that it interposed itself between him “and every innocent girlish heart.” Søren quotes Jesus in Mark 8:36: “For what shall it profit a man if he gains the whole world but loses his soul?” The fact is, before he even met Regine, Søren had begun questioning whether the path marked out for him was one that shouldâor couldâinclude another. These themes will grow to prominence in Søren's later writing career, but for now in these journals we see a young man beginning to wonder whether he might be being called to something besides the comfortable married life of the bourgeois citizen. Glittering wit, like the angel's flaming sword in the Garden of Eden, helps to bar Søren's heart from going to places where it should not go.

This might be God's will, but it is still a lonely life and Søren is ambiguous about his prospects. Like a brick thrown into a pond, Regine has messed up Søren's sense of himself and his plans, causing waves and ripples he never expected:

. . . good God

, why should the inclination begin to stir just nowâhow alone I feelâconfound that proud satisfaction in standing aloneâeveryone will now hold me in contemptâbut you, my God, do not let go of meâlet me live and reformâ

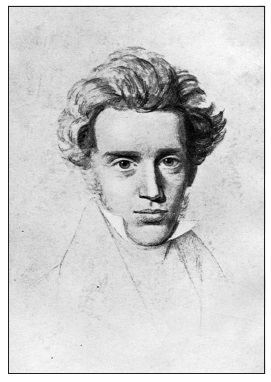

Søren Kierkegaard. This idealized portrait from around 1840 is by Niels Christian Kierkegaard, one of Søren's cousins.

Søren is conflicted. He does not know whether it is better to be a witty loner or an honest lover and is unsure how either fits with the idea to which he wants to devote his life. The journals from this period are confused, repetitive, and self-reflective. They can be annoying in the way that only self-indulgent adolescent diaries the world over can be. But it is good not to judge too hastily. Let the one who has never been young, serious, religious, and in love cast the first stone!

Regine is lodged in Søren's heart, but he does not pursue her further.

The fact is, Søren has a lot of other things going on: spiritually, mentally, and physically. Søren is not well. His back, while not quite hunched, is certainly lopsided, and he suffers from a number of muscular and nervous complaints in connection with what appears to be a twisted

spine. His letters and papers contain many references to headaches, insomnia, aversion to bright light, sensitivity to temperature changes, cramps, constipation, and pain. There is some suggestion that he suffered fits and seizures, although Søren's journals offer scant evidence on this front. In Søren's lifetime and beyond, a litany of diagnoses have been suggested to account for his condition:

compression of the spinal cord

; temporal lobe epilepsy; complex partial seizure disorder; Landry-Guillain-Barré's acute ascending paralysis; acute intermittent porphyria; camphor-induced porphyria; syphilis (contracted); syphilis (inherited); syphilophobia; Potts paraplegia; myelitis. Each item is contested and no one knows for sure. For his part, Søren attributed his fragility to the childhood fall from the tree, but whatever the case, it remains true that he is not what anyone would describe as a strapping young lad.

The physical frailty had a mental and emotional component. One armchair diagnosis that occurs from time to time is that of depression. It is easy to look at the steady stream of gloomy writing (in journal and published form) and conclude that Søren was depressed. Søren describes his melancholy as “depression” time and again too. Yet the diagnosis is too pat. For one thing, depression is a debilitating illness. Truly depressed people do not tend to produce reams and reams of material, working and reworking their ideas long into the evening. For another thing, Kierkegaard's writing is not all miserable. His journals, and later his books, reveal a man fascinated with

all

the twists and turns the inner life takes. The events of Søren's life sparked feelings, thoughts, and reactions in him that everyone experiences but most of us allow to dissipate. Søren captured these sensations, turning them around and around, sometimes spinning dross into gold. Sadness, yes, but also joy, humour, worship, and puppy love can be found in the pages.

Rather than depressed, it would be fairer to say that Søren was mercurial. Not only his writing, but also his actions need to be seen in light of a steady stream of highs and lows keenly felt and never forgotten. “

When at times

there is such a commotion in my head that the skull seems to

have been heaved up, it is as if goblins had hoisted up a mountain a bit and are now having a hilarious ball in there. [In margin: âGod forbid!']” This temperament affected all his most important relationships. Søren's father and brother, his tutors and mentors, his girlfriend, and his God: no one escaped Mercury's sphere, especially not himself.

The period between 1837 and 1841 would prove to be highly significant, not only due to the writing Søren undertook during this time, but also because of the things that happened, both to him and within him. From the crucible of these five years emerges Kierkegaard the author, Kierkegaard the plotter, Kierkegaard the wealthy, Kierkegaard the unhealthy, Kierkegaard the independent, Kierkegaard the Christian, Kierkegaard the lover, and Kierkegaard the scoundrel. Almost uniquely for Søren's idiosyncratically documented life, we can trace the key events of this time, by the month, often by the day, and occasionally by the hour.

July 1837. Marie, Peter Christian's sweet, young wife has died. Everyone is melancholic and Søren feels unwell. In an attempt to clear his head, he arranges to go away to the countryside the day of Marie's funeral. But the trip doesn't come off and it's no use. Relations with brother Peter and father Michael are as bad as ever. The debts are piling up. On July 28 things come to a head. In return for his father's paying off the bills, Søren agrees to leave the family home by the end of the summer.

September 1, 1837. Søren moves into a set of apartments with enough room for his ever-growing library. Michael Kierkegaard values reading, but this enormous collection is a constant reminder of his son's unfocused and profligate ways. Surely he won't be sad to see these books leave his home. Let Søren pay for everything with his own money and see how he likes his library then!

In the autumn following Marie's death Peter's morose religiosity once again rears its head. For his part, Michael can't help but see her passing as yet another flash of lightning from the divine doom cloud looming over his life. Regarding his own faith, Søren remains a conscious outsider. He continues to work out his attitude to Christianity apart from his brother,

his father, and other forms on offer. Living on his own, with no family to answer to and a breach between father and sibling, Søren ceases to attend Holy Communion.

Also at this time Søren begins to make tentative steps towards a doctoral thesis project. He has not yet started, let alone finished, his undergraduate exams, but already the wheels are spinning. In November he muses, “

It would be interesting

to follow the development of human nature . . . by showing what one laughs at on the different age levels.” Søren continues attending lectures on various topics. As an alternative to either rote orthodoxy or vacuous faddish theology, Søren explores philosophy as a way of supplying the idea for which he can live. He attends Martensen's celebrated lecture series on the history of philosophy but finds Descartes'

cogito ergo sum

(“I think therefore I am”) a

“hackneyed proposition”

and Martensen's own appropriation of Descartes' maxim “doubt everything” ridiculous.

“Philosophy,”

writes Søren, “sheds its skin every step it takes, and the more foolish followers creep into it.” Around this time Søren worked out his frustrations with the university scene by sketching out a satirical play called

The Battle Between the Old and New Soap Sellers

. The play (never finished) likens the intelligentsia and their philosophical schemes to the real-life competition currently being waged between Copenhagen's soap merchants who were using increasingly complicated advertisements to sell the same basic product. The play is sophomoric and would be largely unremarkable if not for the fact that it reveals how much of Søren's attitude towards the various philosophic and religious schools of thought had been set, even at this early age.

1838. Early spring. There is a gap in the journals. In April, Søren breaks his silence, revealing why. “

Such a long period

has again elapsed in which I have been unable to concentrate on the least little thingânow I must make another attempt. Poul Møller is dead.” Møller was forty-four years old. He was Søren's teacher and confidante and the model for the way Søren would carry himself as an assessor of the foibles of public life. One day Søren would go on to dedicate a book to Møller, the drafts

of the

Concept of Anxiety

dedication reading: “

To the late Professor Poul Martin Møller

. . . the mighty trumpet of my awakening . . . my lost friend; my sadly missed reader.”

The dedication lies in the future. At the present moment, matters are made even more galling because Martensen has attracted the patronage of Heiberg. As a result, he is appointed to replace Møller's position at the university. It is a temporary position but one he will hold for the next two years before being made a full professor. Lest it be forgot, at the same time as Martensen is taking on the mantle of Copenhagen's golden boy, Søren, only five years younger, has yet to complete his undergraduate degree.