Kierkegaard (8 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

One such source of public chatter was the theatre, where Søren could be found almost nightly. Søren loved the melodrama of opera, and he was a keen observer of the actor's craft. And if the eyes of a beautiful woman just happened to be caught from across the stalls, what harm was there in that? Copenhagen's Royal Theatre, however, provided more than merely drama or an occasion for innocent flirting. The place was a meeting of likeminded souls. Søren was part of a group (which included Hans Christian Andersen) of civilised contemporaries, up-and-comers in Copenhagen's chattering class. Every night, literary figures, ambitious politicians, newspaper men, and students would congregate. In between acts, the theatre would be alive with the buzz of witty men discussing the latest ideas when they weren't discussing each other.

Søren was gaining a reputation as one of the wittiest and cleverest of the bunch, due in large part to his student activities. Søren may not have been a keen theologian, but he was active in other university circles and he was making a name for himself in this sphere. Søren attended lectures in psychology, poetry, history, and philosophy. He does not seem to have loved any of these subjects, but two philosophy lecturers in particular were to catch his attention, and he theirs. Søren became friendly with Frederik Christian Sibbern, who taught aesthetics. Sibbern was a serious man, averse to affectation. He wrote complicated, dense texts, but he was also a poet. His daughter remembered Søren's visits to the family home,

where the two men talked into the long evening “

when the fire gleamed

in the stove.”

The other key person in Søren's education was Poul Martin Møller. Of the two favourite professors, Møller's life was the more colourful. Before taking up his post at the university, Møller had served as a ship's chaplain. He too was a poet and a celebrated public figure. There is little indication of how much Søren actually learned from Møller's philosophy lectures: it was Møller's style and personality that won him over. Møller also lived in a house on Nytorv and was known to frequent the same cafes as Søren. An early champion of the idea that one should authentically inhabit one's ideas, Møller was a sharp critic and a keen satirist, who, to Søren's delight, could easily puncture the pomposity of Copenhagen's intellectual elite.

The prime source of puffed-up cultural superiority in nineteenth-century Europe was the German thinker Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. One of Hegel's Big Ideas was that the historical development of art, religion, and philosophy told us something true about the development of the Divine Mind in the universe. The revelation of God was not to be found in a person or a holy text but in the development of a culture's history. The unfolding Spirit is first encountered in a society's art. This artistic expression is then given meaning and explanation in that society's religion. Finally, it is philosophy that explains the religion. The Spirit is ever developing and thus the Divine is revealed in mankind's highest achievements. To see the latest and best manifestation of the Divine Mind in the world, all one has to do is look at the latest and best manifestation of the world's civilisation. The reader will be given no prizes for guessing whose art, religion, and philosophy the Western European Hegel thought was currently sitting on the top of the civilizational pile.

Hegel was (and is) a towering figure in Western philosophy. His influence was (and is) immense, even where his name goes unacknowledged. Hegel and his followers have a hand in such apparently opposite

movements as the Manifest Destiny of American exceptionalism, the class-war struggle of Marx's dialectical materialism, and the triumphalism of the Third Reich. Both the liberal myth of progress and the conservative myth of the Golden Age owe Hegel a debt of gratitude. Wherever one finds a commitment to one's culture and history as itself being a vehicle for truth, one finds Hegel's fingerprints.

If you were an academic or literary figure in Denmark in the 1830s, Hegel was inescapable. Either you were setting yourself against him and his systematic view of culture or you were seeking to align your favoured theories with his. Either way, you were grappling with the knotty Swabian. As with the rest of Europe, much of the Danish scene at this time saw authors, philosophers, theologians, and churchmen finding ways to articulate their innate sense of cultural superiority along Hegelian lines.

Sibbern and Møller were no different. Sibbern had to account for Hegelian dialectic in his own aesthetic philosophy. He questioned the Hegelian presumption that one could approach a subject without presuppositions and attain some sort of neutral, objective point of view. By 1837 Møller was offering a sympathetic critique of Hegelianism, based in part on Hegel's inability to account for individual experiences. What marks Sibbern and Møller apart from many of their contemporaries at the university is a healthy scepticism about the pretensions of many of Hegel's Danish followers. It is from them that Søren must have begun to form his own approach to Hegel: a respectful yet critical reading of the master coupled with fierce and unrelenting attacks on the affections of his self-styled disciples. Hegel yes, but especially the Danish Hegelians would be a primary target for the rest of Søren's life.

The main disciple was Hans Lassen Martensen. Long before he became the bishop overlooking Søren's funeral from afar, Martensen was a promising young theologian. In the 1830s he was gaining a reputation in church and university circles as an exciting communicator of complex ideas, especially Hegelianism, of which Martensen was an

early champion. In his lectures and publications throughout this time Martensen developed his take on the typical Hegelian view that the established church, culture, and state are crucial to religion and part of Christianity's inevitable progress. Martensen was also adept at teaching on subjects such as Cartesian philosophy and modern theology, and Søren engaged him as a personal tutor in the summer of 1834. True to Søren's form, studies with Martensen were not focussed, and Martensen seems to have been given free rein to choose the subject. Martensen led Søren through readings of Schleiermacher, the eighteenth-century “father of liberal theology.” Open warfare between the two men was still years away, but it is safe to say the two did not hit it off. At twenty-six, Martensen was five years older than Søren, not old enough to command respect yet still young enough to pose something of a professional rival. It is clear that Martensen's popular style rankled Kierkegaard as much as his subject matter. That a complex set of thoughts could be packaged and presented in an easy manner bothered Søren. In later years, he would cast a critical eye on the young Martensen who “

fascinated the youth

and gave them the idea they could swallow everything in half a year.”

For his part, Martensen claims not to have been impressed with the callow Søren either. In his memoirs, also written long after Kierkegaard had become an avowed enemy, Martensen paints a picture of a mentally sharp but emotionally unbalanced man with

“a crack in his sounding board.”

It is from Martensen's memoirs that we get a unique anecdote, which Martensen intends to demonstrate Søren's temperament. Søren engaged Martensen in the same summer of 1834 that his mother, Anne Kierkegaard, died. At this time Søren paid a visit to the Martensen family home and met with Martensen's mother. “

My mother has repeatedly confirmed

,” Martensen writes, “that never in her life . . . had she seen a human being so deeply distressed as S. Kierkegaard by the death of his mother.” From this Mrs. Martensen concluded that Søren had “an unusually profound sensibility.” Why did Martensen include this curious story? It was certainly not to redress the utter lack of mention

of Anne Kierkegaard in Søren's own writing. Instead, Martensen offers this incident as demonstration of how Søren's development became stunted. As the years passed “the sickly nature of his profound sensibility” increasingly got “the upper hand.” Of their tutorials together, Martensen comments, “

I recognized immediately

that his was not an ordinary intellect but that he also had an irresistible urge to sophistry, to hair-splitting games, which showed itself at every opportunity and was often tiresome.”

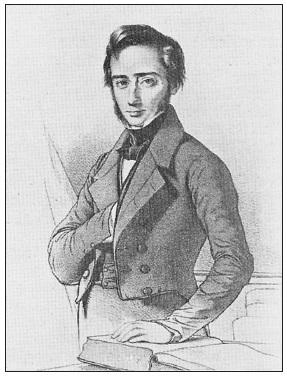

Hans Lassen Martensen, a promising and popular academic and a private tutor to Kierkegaard. Søren dismissed Martensen as one who “fascinated the youth and gave them the idea they could swallow everything in half a year.” For his part, Martensen claimed that Kierkegaard had “a crack in his sounding board.”

It was not only Søren's enemies who noticed his tendency to latch, terrier-like, onto an argument and not let go. His friends too were concerned that his contentious nature would get the best of him. After one social engagement, Møller berated Søren for being so

polemical

all the time, a caution that Søren took to heart and mentioned in his journals more than once. Nevertheless, it was his arch, argumentative manner that catapulted Søren into the public consciousness.

Søren's first published works were examples of rhetoric and juvenile satire. An 1834 essay entitled “A Defence of Woman's Superior Capacity” was printed in

The Flying Post

, a showcase for new writers and their ideas. The piece strains to be clever and funny about serious issues, a form typical to student journalism then as now. More significant for his reputation was the public debate that Søren undertook in the autumn of 1835. In November, J. A. Ostermann, an up-and-coming political leader, gave a paper to the Student Union in favour of increased liberalised press freedom. Two weeks later, Søren volunteered to offer a rebuttal. It would be his first foray into public debate. In the talk, titled “Our Journalistic Literature,” Kierkegaard took the position against freedom of the press and, crucially, its sense of self-importance. He argued that the recent political reforms the press had been claiming responsibility for had, in fact, originated from the government. The presentation was hailed as a success from many quarters. Ostermann was impressed by the

“brilliant dialectic and wit”

Søren showed at puncturing his arguments, but he did not bother to engage further with the dilettante. Ostermann recognised that Søren was not a serious political sparring partner. “I knew [he] had only a slight interest in the reality of the matter.” Søren seems to have chosen the position for largely polemical, rhetorical reasons, but in any case he continued the attack in the newspapers for the next few months under the pseudonym “B.” These pieces were also feted and after a bit of speculation in the student press, Søren was “outed” as the true source.

As a result, Søren garnered a reputation amongst Copenhagen's literati. The circle was led by Johan Ludvig Heiberg and his wife, Joanna,

an actress and celebrated beauty. A leading light of what would come to be known as Denmark's “Golden Age,” it was J. L. Heiberg who was one of the first to introduce Hegel to the Copenhagen scene. He was also an accomplished playwright and dramatic theorist who aligned his aesthetics with Hegelian systematics. Heiberg was the editor of

The Flying Post

and other literary journals. His attention could make or break careers, and he knew it. It is not hard to imagine young Søren's beating heart and trembling fingers as he cracked the seal on the invitation to his first Heiberg soiree.

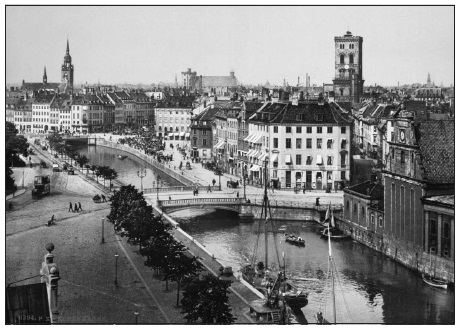

A view of old Copenhagen

Søren was a hit. He soon gained a reputation for his quick mind and witty repartee. Kierkegaard would go on to become a regular fixture at the salon parties, which included luminaries of the age such as the scientist H. C. Ãrsted, Hans Christian Andersen, Møller, and Martensen. Søren seemed to be taking to this world like a duck to water. Yet the journals of this time reveal the furious paddling going on just under the surface. In one entry Søren likens himself to a two-faced Janus: “

with

one face I laugh, with the other I cry.” “

People understand me so little

that they do not even understand my laments over their not understanding me,” he wrote after one such soiree. And after another: