Kiss and Make-Up (22 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

Every once in a while I would see a band that I knew was going to be big. Van Halen was one of them. I saw them in a club, the Starwood, in 1977. I went with Bebe Buell, a model who was friendly with a number of rock stars. (She’s perhaps better known today as the mother of the actress Liv Tyler.) Bebe and I were going to see a band called the Boyzz, and opening was a new band called Van Halen. Within two songs I knew they were going to be huge. Strangely, they did only okay at the club. People liked them, but it wasn’t a maniacal response. But I knew. I went backstage, went over to them, and introduced myself. I went right into business mode. I wanted to know their plans. They had a potential backer who was a yogurt manufacturer. I said, “Please do me a favor—don’t do that. I’ll fly you to New York, I’ll produce your demo.” I signed them to a contract.

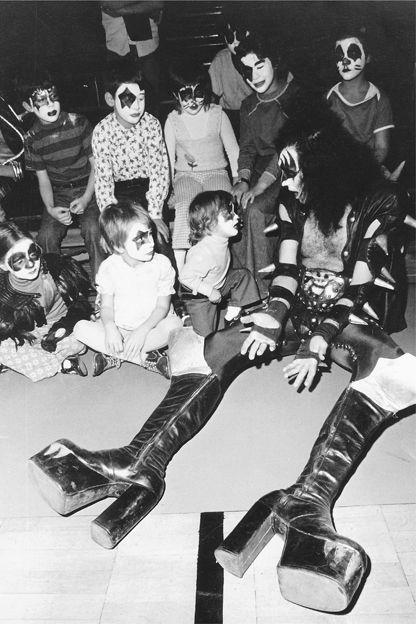

We played in Cadillac, Michigan, in 1976. The football coach at the high school used KISS music to motivate his players to a state championship that year. When we arrived in Cadillac, everyone in the town was dressed up in KISS makeup.

(photo credit 9.2)

Immediately I started to bring them around. In Los Angeles we went into Village Recorders, and in New York City I bought David Lee Roth some leather pants and belts and platform shoes. Then I produced their demo at Electric Lady studios—thirteen to fifteen songs, most of which wound up on the first and second albums. Some of those were my arrangements. The next step was to try to convince Bill Aucoin and the rest of KISS to sign them. But the rest of the guys in the band were angry that I was turning my attention to other acts, and Bill Aucoin thought Roth looked too much like Black Oak Arkansas. He didn’t get it. I told Eddie Van Halen and the others that even though they were signed to me, I would try again after KISS toured. Within two or three months, Van Halen got interest from Warner Bros. I said, “You go for it. I’ll tear up the contract, just go.” Though this was the first time I got interested in a younger band, it was by no means the last—I would have plenty of other opportunities to work with groups starting their careers, or to help remake the careers of older artists. Working with bands other than KISS was liberating in some respects, because I could share everything I had learned about the record business. And often naïveté about the business is what does young bands in.

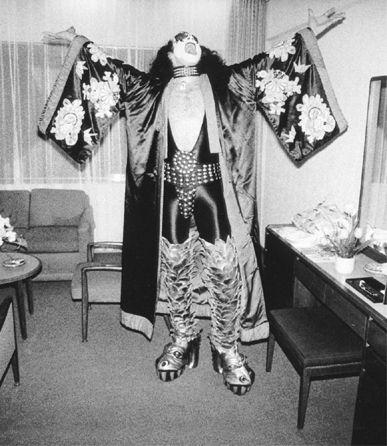

Relaxing in my hotel room during the Japanese tour.

(photo credit 9.3)

KISS had conquered America. We had conquered Europe. And then in early 1977 we went to Japan to play a series of sold-out shows at Budokan in Tokyo. We learned later that we had broken the Beatles record there. We didn’t know anything about Japan. When we landed there, we did the same thing that we did in England, which was to walk off the plane in full makeup and outfits in case there were any reporters. Well, that was a great plan, except that the Japanese customs officials didn’t let us into the country, because they didn’t believe that we were the same people as those pictured on our passports. So we had to take the makeup off, pass through, and then put it back on before we went outside.

When we finally emerged from the airport, there were about five thousand Japanese fans outside. The Japanese promoter, Mr. Udo, had arranged to have duplicate cars, and most of the fans ran after the duplicates while we snuck out the back and jumped into other cars. But enough of the fans figured it out and came after us. I really thought we were going to die. There were just so many people, crushing us. They were on top of the cars. They could physically lift up the car. It was major KISS mania, like what you see in the Beatles’

A Hard Day’s Night

, but bigger because the cars were being rocked and rolled, and it wasn’t just girls but guys as well. We later learned that the Japanese fans felt a great kinship with us because of our makeup, which looked like kabuki theater makeup, and also like the Japanese superhero shows. In the same way that some of our early American fans were black, because they didn’t see us as either white or black, the Japanese took to us because they didn’t see us as American or Asian.

The girls in Japan were also wonderful, very willing and very available. The interesting thing about Japanese women, in my experience, is that they have a little girl quality, a certain innocence about their sexuality.

Coquette

is a French word, and that concept just doesn’t exist in Japan, at least as far as I saw. For instance, when

Japanese girls orgasm, a peculiar sound emanates from them that almost sounds like a baby crying.

Japan wasn’t just another country; it was more like another world. Within the country, we traveled by the bullet train, the fastest train in the world. The Japanese fans, and especially the girls, would follow us everywhere we went. They would giggle, give us presents, and break into hysterical crying fits in front of us.

Peter brought Lydia, his wife, with him on the Japanese tour, so outside of work we didn’t see much of him. Ace, on the other hand, was full of piss and vinegar. One night he knocked on my door and appeared in front of me drunk out of his mind in full Nazi uniform with his friend, saluting and yelling into my face, “Heil Hitler!” I have pictures. Ace knew how I felt about Nazi Germany. He knew that my mother had been in the concentration camps and that her whole family had been wiped out. But that didn’t stop him. Many years later, during the 2001 KISS farewell tour in Japan, drummer Eric Singer (who had taken over for Peter Criss at the time) jokingly started calling Ace “Race Frehley.”

During one of our off days in Japan, the band went to a nightclub, where we were met by a gentleman who introduced himself as Gan. He was stout and powerful and could clearly take care of himself. We didn’t speak Japanese, so we relied on translators. We went over to our VIP section, and within seconds girls started to line up and pass by us and giggle. The man next to me was of some importance, I could tell, because when he put a cigarette up to his mouth, two other men nearby immediately lit it for him. We exchanged pleasantries. I learned later that he might be from the

yakuza

, the Japanese mob.

One of the girls in the crowd reached out, and we shook hands. Gan broke off the contact, spit in her face, and raged at her in Japanese. She cried and ran off. The translator explained that Gan was merely doing what he thought was proper. He was there to protect us, and she was not “worthy” of touching me. This was clearly a completely different culture.

At one point I got up to go to the dance floor, and security men followed me. Most of the Japanese are smaller than Americans: a

Japanese girl might be five-two. One of the girls, a beauty about five-eight, made eye contact with me. I immediately went over and took her hand and pulled her toward the dance floor. She smiled. I told her I wanted to go back to the hotel, but the music was too loud. All she did was keep smiling. We got inside the hotel and I tried conversation, and then it dawned on me that she couldn’t speak a word of English. It didn’t seem to matter, though. We didn’t need to talk. The next day one of our security guards told me she was a famous Japanese television star. Right before commercial breaks late at night, Japanese television would show a shot of a beautiful, naked girl smiling into the camera. When we got back to America, our KISS press office showed me a press clipping from Japan. There she was, smiling her smile in front of countless members of the Japanese press. The translator explained that the title of the article was “My Night of Passion with Gene Simmons.” I didn’t mind. I was actually quite flattered. She was gorgeous.

Even though

Love Gun

, which was released in 1977, was our third album in a row to ship a million copies, the band came apart at the seams during that time. It wasn’t that we were breaking up, but people were starting to need their own space again. We had been together for five years, which is coming up on the typical lifespan of a band. I always had the sense that the Beatles were around forever, but when you look at the number of years, it’s astonishing how brief they were: only a decade of existence, and only seven years of recordings, from

Meet the Beatles

to

Let It Be.

The strain was pulling us apart, but it was also pushing us forward, into new projects and uncharted waters. From the beginning I had been heavily indebted to comic books, and in 1978 we made good on that relationship by getting a comic book of our own. First a Marvel artist named Steve Gerber who was a big fan put us in the last two issues of

Howard the Duck.

We were demons who possessed Howard. Marvel noticed that those two

Howard the Duck

issues soared in sales even though we weren’t on the cover. So they approached us about a KISS comic book.

Someone arranged for me to meet Stan Lee, the head of Marvel. He was a god to me. As a kid, I had sent a letter to Marvel critiquing something, and I actually got a postcard back, signed by Stan Lee, saying, “Never give up.” It was signed, “Stan.” And I thought,

That’s it, I’ve made it.

Marvel comics were so important to me, because heroes like Spiderman had these screwed-up lives that contrasted with their superhero lives.

Superman

, which was a DC comic, was a classic concept, but I didn’t read

Superman

as loyally. He wasn’t a teenager. He didn’t have problems.