Kiss and Make-Up (26 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

I wanted my solo album to be the greatest show on earth, with choirs and tons of special guest stars. My initial vision included everyone from Lassie to Jerry Lee Lewis to Lennon (who was still alive then) and McCartney. These weren’t all possible, of course. Jerry Lee Lewis couldn’t make it as a result of a scheduling conflict. Lassie too had a scheduling conflict. As for Lennon and McCartney, I called up their management and made an offer for them to appear on the album. When they said no, I hired two guys from

Beatlemania

, the Beatles tribute stage show, to do the singing.

I didn’t replace Jerry Lee and Lassie, but the final record included many, many guest appearances. Early on, I took over Cherokee Studios in Los Angeles and called on musicians from other bands to come and help me do the demos of the new songs. Joe Perry from Aerosmith came down and played a killer solo on one of the new songs. Katey Sagal, who I saw for a short time around the same time I was seeing Cher, and two other girls from The Group With No Name sang on a few others. I excitedly played Cher the new songs I had been working on, but usually a blank look came over her face. She never really understood our music. While I was telling her about my new songs, she would be telling me about her dreams to remake

The Enchanted Cottage

, a movie she loved. We were both dreamers.

As I went on with the solo project, I wanted to pursue my Beatles obsession, so I rented a recording studio in Oxford, England, down the road from where George Harrison lived. Anytime I wanted another star to appear on the record, I flew them in and treated them like royalty.

I tried to make a point—a showy point, granted—that I was capable of playing guitar. So on the album I didn’t play bass at all, I only played guitar. Cher and Chastity appeared on one song called “Living in Sin at the Holiday Inn.”

Sean Delaney produced my solo record, and he brought in Michael Kamen to arrange and conduct about thirty of the finest string players in Los Angeles. One morning they had arrived and were seated inside the recording studio ready to do their parts on a song I had written called “Man of 1,000 Faces.” Sean had arranged to have them all wear Gene Simmons face masks, the ones that were for sale in stores. It was certainly one of the most bizarre moments in my life: to open the door to see a roomful of violin players all looking like me.

On another occasion I had Janis Ian at the studio at the same time Grace Slick came down to record with me. I had met Grace on tour, because she was seeing our lighting director and would visit him on the road. Janis, Sean, and I were discussing some ideas, when suddenly all hell broke loose. Grace had apparently ingested some chemical that didn’t agree with her constitution. She flipped out, and studio staff helped her out of the studio.

Other pairings were just as exciting. Helen Reddy came down to sing on a song called “True Confessions.” I had Ping-Pong tables set up inside the recording studio, and Helen and I played Ping-Pong. Donna Summer did me the favor of singing with me on “Burning Up with Fever.” She blew the roof right off. We got along well. By that time she had become our record company’s next big thing. KISS was the first act to sign with Casablanca, and Donna was up-and-coming at the label. And Bob Seger, another hard-driving rock and roll vocalist, sang with me on “Radioactive,” which became the single off the record. We had known Bob for many years—earlier, he had opened for us on a tour.

At one of the shows, while Seger and his band were getting

ready to go onstage, I stood alongside Alto Reed, his horn/sax guy. Alto mentioned that he needed something to drink—he said his mouth was dry. I offered him a piece of gum, which he said he would start chewing right away. That night was a strange one for the Seger show. You see, at that point in my life, I loved pranks and would often buy whoopee cushions and the like. I also bought Onion Gum, which looks like gum and tastes like gum initially—until about the tenth chew, when a horrid onion taste explodes in your mouth.

The solo project was unprecedented. No other group in history had ever released four solo albums simultaneously. Even though the solo albums were a way for Ace and Peter to feel they had a bit more creative control, we were intent on controlling the project. Both our management and our record company—Casablanca released all four solo records on the same day in 1978—insisted that each album have the same kind of artwork. We all used the same artist, Eraldo Carugati, so the entire project felt like a coordinated band solo release, something that has never been done before or since.

All the albums did well: they sold strong initially and have continued to perform. After twenty-plus years of sales figures, I’m at the top, slightly ahead of Ace, who is slightly ahead of Paul. Peter’s sold the least well of the four. None of the albums really yielded hits. The song that got the farthest was Ace’s cover of a song called “New York Groove,” which went to number 14. Peter didn’t chart. “Radioactive,” my single, stopped in the twenties, and Paul’s “Hold Me, Touch Me” was a little lower than that.

The solo album was a big boost for Ace. For the first time he was thrilled, because he could walk into a room and be the only star, the guy who had his own thing going on, his own album with his own face on the cover. The irony was that when he first joined the band, he didn’t want to sing or write songs. He just wanted to be the guitar player. We had forced him to start writing songs. Once he found out he could do it, he actually delivered the goods. He was able to put out an album that in a lot of ways was probably the most cohesive of the four.

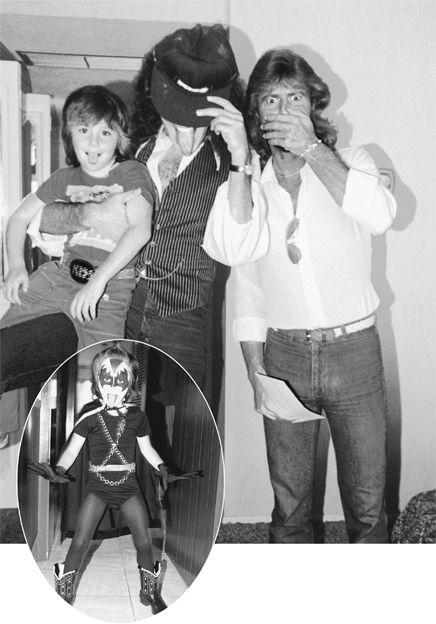

In the late 1970s, the Bee Gees were arguably the biggest band in the world, but Barry Gibb’s son Steve just wanted to dress like me!

The solo albums sold about a million each. But Casablanca was accustomed to having two albums a year from us as a band, and they didn’t count the solo ones. So just after that, Neil Bogart put out a greatest hits record,

Double Platinum.

I had to go back to New York and start getting ready for the next KISS tour, and I wanted Cher and the kids to come live with me. I went to F.A.O. Schwarz and bought a six-foot-long bed shaped like a sneaker for Chastity. They all came with a nanny, and when Cher saw my condo, she said it wasn’t big enough and moved into the Pierre Hotel.

It soon became clear that if I wanted Cher to be with me in New York, I would have to finally buy a home that would suit her. So I went shopping for a larger place. Cher and I were refused at the Dakota, where John Lennon lived. We were deemed to be too much trouble, because the press was on our tail night and day. I finally found a space I thought she would like: the top floor of the former Heart Fund building, on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Sixty-fourth Street, across from the children’s zoo at Central Park. There was nothing on the top floor then, so I bought “air rights,” which meant that I could build a dwelling on the entire top floor of the existing building. I hired Cher’s architect from California and flew him to New York. While the penthouse was being built, KISS went out on tour. When we came back home, I took the elevator up to the penthouse. It opened up into my floor. There were Romanesque columns and a giant bathtub in the middle of the larger bedroom, with marble all over the place. It was a showpiece. Cher loved it, and so did I. The problem was that by the time it was finished, Cher and I had stopped being lovers and were back to being friends.

The headaches with the other two guys in the band continued. Peter was depressed, Ace was as infuriating as ever, and both of them were increasingly being controlled by substances. Ace’s behavior was probably more interesting, although no less maddening.

Ace has always struck me as never living up to his potential. He could play guitar, write songs, and do any number of other things. But he’s never applied himself. He’s admitted to being chronically lazy and a flake. He can put an idea together that has a spark of brilliance. But he won’t go that extra mile to get trademarks and copyrights. You can see hundreds of guitar straps today, for example, with big lightning bolt designs on them, straps that are used by everyone, from country acts to rap bands—that’s Ace’s design. He walked in one day with this strap, and I said, “That’s great. Let’s trademark that. It’ll sell like hotcakes.” I had a heart-to-heart talk with him. He just wouldn’t do it. After the fact I said, “You really missed out on a big one.”

“Ah,” he said, “I’ll think of another one.” He never did.

With these kinds of headaches in the band, there were plenty of times I would have preferred to stay with Cher. But whenever I sat down and thought seriously about things, I realized that, at least at that point, I would never risk breaking the band up or leaving. It was all-inclusive and invasive. So in one way I sort of forgot that I had any options; I gave myself completely to the band and defined myself that way. I was Gene Simmons from KISS;

from KISS

might as well have been my last name. Soon enough the four of us were in contact again. We didn’t tour in back of the solo albums. We were talking about meeting in New York to record a new album. This one we decided to call

Dynasty.

DYNASTY

was recorded

in New York City with Vinnie Poncia, who had been Peter’s producer for his solo album. Paul and I had met with Vinnie at Bill Aucoin’s suggestion, in part to show Peter that we thought well of his record and to bring him back into the fold. By that time Peter was our biggest liability, because he had become dependent on chemicals. Ironically, Vinnie decided that even though he produced Peter’s record, he didn’t think Peter was good enough to drum on a KISS record. Peter was not qualified to make any judgments about material or arrangements, he said. In Vinnie Poncia’s estimation, Peter was close to tone deaf and didn’t play drums well enough.

At times I have reassessed my criticisms of Ace and Peter. Sometimes I have to remind myself that everybody has their cross to bear. If I were Ace or Peter, I would find Gene Simmons very difficult to take. I’ve never been high, except in a dentist’s chair and that one incident with the brownies, and I don’t have much use for small talk. Whenever I spoke to Ace and Peter, it was to get information: who, what, why, when, where, and how. They just didn’t deal well with that. We would have numerous meetings before a tour or recording session, and they just couldn’t sit still. They’d be cracking jokes and throwing food at each other, and every time, at the end of the meeting, they would ask me, “What was that about? What were you saying?” Or a day later they would ask, “Okay, when are we going to talk about the album?” And I would have to explain that we had talked about it, and that they had agreed to certain terms. Nothing would stick. Ace and Peter didn’t take notes, didn’t read memos. It was a bull-in-a-china-shop situation: they would come into a room not knowing where anything was and figuring that whatever was going to happen was going to happen.