Kiss and Make-Up (34 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

I enjoyed working on the movie, but my film career was really starting to irritate Paul and management. They wondered if I wanted to stay in the band or go for an acting career. The answer was that I wanted it all. But that wasn’t entirely fair to Paul, who was committed to KISS full time.

I acted in another movie called

Never Too Young to Die.

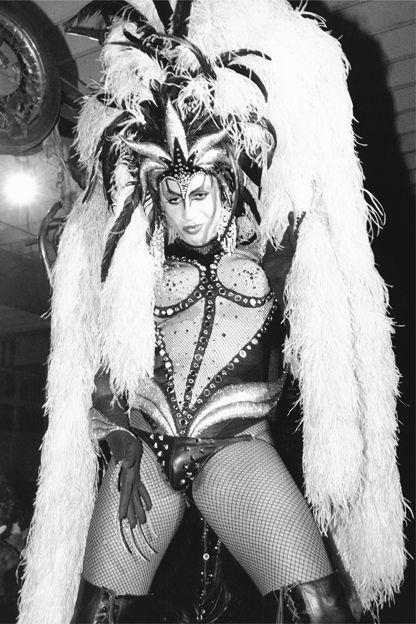

This time I played two roles, one as a CIA agent, and the other as his alter ego, a transvestite rock star named Ragnar. I wore stiletto heels and a bra with a corset attached. I wore women’s makeup. I wore fishnet stockings. I looked like an evil painted woman.

One day after I had gotten into my full getup, I started to teeter my way onto the set. Along the way I passed the trucking crew, who promptly ripped me a new asshole: “Hey Gene, lookin’ good.” “Hey, what are you doin’ later, baby?” I hated it. During one of the scenes, I had to mouth an old Wayne County line: “It takes a man like me to be a woman like me.” My backup band were real transvestites who gave me tips on how to be convincing. The movie also starred John Stamos and Vanity, who enjoyed flirting with me almost as much as I enjoyed flirting back.

Then in 1986 I was offered a film called

Red Surf.

The cast included Dedee Pfeiffer, Michelle’s sister, and George Clooney. I played a Vietnam vet who has had his fill of killing. At the end of the movie I had to come and save everyone from certain death. I was getting accustomed to the movie business.

The band without the makeup in 1988—me, Paul, Eric Carr, and Bruce Kulick.

I was living in California with Shannon while the rest of the band was in New York. Eric was working out just great on drums, and the whole touring environment was stressfree for the first time, now that Ace and Peter were no longer in the band.

By 1987 KISS had gone through a series of guitarists. We had brought in Bruce Kulick in 1984. In an odd coincidence, Bruce was the brother of Bob Kulick, who had auditioned for KISS at its inception. While Bruce lacked a personal style, he was quite accomplished and was willing to reproduce Ace’s solos from the records. Bruce has always been a professional, and being in the band with him was a joy. Initially he lacked a certain stage presence, but though he was sensitive about his shortcomings, he was willing to work to become a better stage performer.

Paul was looking for other ways to express himself, including acting. He would later go on to star in the stage version of

Phantom of the Opera

and closed the show after 150 performances in Toronto. Then he decided to put together a solo band, the Paul Stanley Band, and go out on his own tour. His band consisted of Bob Kulick on guitar and a drummer named Eric Singer. I went to see Paul perform and sat up in the balcony with Eric Carr. It was interesting, actually, watching Paul from the audience instead of standing next to him onstage. Eric Carr was concerned he would be replaced by Eric Singer, who was a terrific drummer and singer. At the end of Paul’s tour, the two of us turned our attention back to KISS.

We were now making more money than we had even in the glory days of the 1970s. Gone were the excesses of management perks, inefficient stage designs, and expensive recording sessions. In 1989 I found an inexpensive demo studio, and we recorded our next album,

Hot in the Shade

, there. It was done for a fraction of our usual costs, with no producer fees involved. We produced it ourselves.

Paul wrote a song with Michael Bolton called “Forever” that made it into the Top 10, and the ensuing tour was a big success. We had a forty-foot-high sphinx in the center of the stage, and we appeared in the mouth as the eyes were shooting flames and fog came out of the nose. With or without makeup, KISS was selling out concerts again.

It takes a man like me to be a woman like me: dressed up as a transvestite for my role in

Never Too Young to Die

in 1985.

(photo credit 14.2)

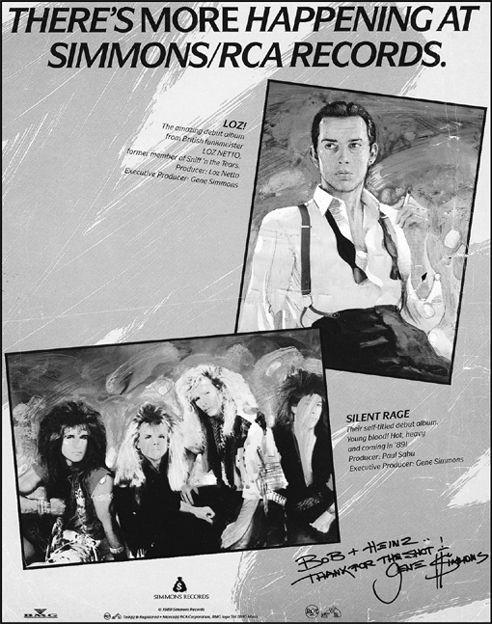

Life has given me the opportunity to take advantage of my whims, at least to the point where I can get doors opened. One day I was sitting around thinking of other projects that interested me, and it suddenly occurred to me that I would like to have a record label. I had always taken an interest in younger bands. If there was a Geffen Records, I thought, why couldn’t there be a Simmons Records? At the time the RCA label didn’t really have a strong rock and roll presence, which seemed unfortunate to me—it had been the home of Elvis Presley. RCA seemed like a promise unfulfilled. As usual, I didn’t bother with lawyers or complicated proposal letters. I just got on the telephone and called Bob Buziak, the president of RCA. I didn’t get him; instead I got Heinz Henn, the European head, who had seen KISS in several German shows. Henn, Buziak, and I met, exchanged views and philosophies, and before I knew it, I had a record label: Simmons Records.

The first album my label released was a self-titled debut by a band named House of Lords, which featured a guy named Greg Guiffria. He had been in a band named Angel that had signed to Casablanca Records on my recommendation, and then after that he had a band named Guiffria that had a big hit in the mid-1980s, a song named “Call to the Heart.” I signed Greg only on the condition that I would executive-produce his record—I would have full control over the name, the look, everything. I didn’t want the name to be Guiffria. I wanted them to be House of Lords, which was a name I owned and had trademarked. I wanted to direct their image. That record went to number one on the U.K. import chart before it was ever released in the United States.

Other bands followed, including a California rock band called Silent Rage. But the original concept got a bit blurred over time. For example, a band called Gypsy Rose was an act that RCA found. I didn’t have anything to do with it, but they wanted me to put it out on my label for credibility purposes. I also courted Joe Walsh for a

solo record and was managing, producing, and writing for many artists. I was still in KISS, and even if I wasn’t devoting my full attention to the band, I knew it had to remain a top priority. Pretty soon it became clear to me that there just were not enough hours in the day for me to manage my own label. When the time came, RCA didn’t pick up the option, and Simmons Records disappeared. As I write this book, though, I am talking to several major labels about reviving Simmons Records.

The joint venture I had with RCA, Simmons Records, promised to be the beginning of a brand new career for me. At this point I was relatively unhappy with KISS and was looking for other ways to creatively express myself.

During the summer break from the

Hot in the Shade

tour, I came back to L.A. and to Shannon. I had it all. KISS was doing well; I was living with a queen. What else could I want? I was about to find out. One evening Shannon and I went to a Neil Bogart Memorial Cancer Fund event, which was being held at the Santa Monica racetrack. I was talking to Sherry Lansing and Joyce Bogart, and the conversation turned toward marriage. I mentioned how scared I was of marriage. Well, Joyce said, “What about kids?” Before I could utter a word, Shannon said, in a voice just above a whisper, “I’m pregnant.”

I didn’t hear her say it, not consciously. I heard the words, but they never connected with my brain. I never thought I would ever hear those words from anyone. I remember feeling dizzy as the blood rushed to my head. Before I knew it, Shannon and I were alone and facing each other. Everyone else had left us. I didn’t say anything—I was holding my breath.

So here it was, finally: the day I never thought would happen. What was I going to do? Would I accept my responsibility? More important, was this something that I might have wanted all along but never had the courage to admit to myself?

I looked into Shannon’s eyes and saw that this was something she really wanted. I can’t tell you why, but at that instant I knew I wanted the same thing. I wanted to be a father. It wasn’t the notion “Well, this is supposed to happen.” I just knew it deep inside.

Over the course of her pregnancy, Shannon became quite voluptuous and even more desirable. She was sexy and curvaceous. I couldn’t keep my hands off her. As the pregnancy went along, we joked that she needed a suit of armor to protect her from me.

I had become something of an expert at keeping my emotions under control. Suddenly, pure white fear started to creep in.

Oh, my God

, I thought,

there’s gonna be a baby. Is it going to be a boy or a girl?

And,

Oh, my God—what if it’s a girl? How do I talk to a girl?

All these things that I never verbalized, that I never even dared think of, were suddenly upon me. I was a wreck, I have to say. Shannon had a little morning sickness—it was nothing out of the ordinary

for a pregnant woman. But for me it was all out of the ordinary, and I was very concerned about her and the baby.

KISS went on tour to Europe and I took Shannon along. It was the first time I had taken a girl on tour with me. I tried to explain what touring was about. She saw girls lifting their tops during the shows. She answered the phones when the girls would call. She was a good sport about it.

When we were in London to play Wembley Stadium, I saw a girl I may have had a liaison with, I can’t recall. I mentioned this to Shannon, who was now visibly pregnant. The girl followed me around, and one day I answered the front door to find her standing there. With Shannon in the background, she offered to kick Shannon’s stomach to kill the baby. She ran off when she heard Shannon coming.

When we came back to America, we went to see a doctor. At one point he asked if we wanted to know the sex of the baby. We did, so they set up an ultrasound machine to look into Shannon to actually see the outline of the baby. This was about a month before the birth. I thought I was watching a science fiction movie, with the baby inside, moving. “So,” the doctor said, “I suppose you’d want to know that you’re going to have a boy.”

“Well, yeah, sure,” I said. “I can tell.” I thought that he was going to be the most well-endowed son on the face of the planet. But it turns out that what I was looking at was the umbilical cord. The thing looked longer than his leg, which, in fact, it was. But what did I know about umbilical cords? I just wanted the best for my son.