Kiss and Make-Up (36 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

Eric showed up and stayed until the very end of the video shoot, which lasted until three in the morning. He never complained, not once. I believed that he could somehow turn things around.

It was not to be. During the recording of

Revenge

in 1991, Eric Carr passed away. We were devastated and flew to New York for the funeral. Ace showed up as well to pay his respects. We said hello to each other but sat in different parts of the church. The fans lined the driveway leading up to the church, and everyone was in tears. The fans had loved Eric, and they weren’t the only ones. It devastated everybody. Whether Ace cared for Paul or myself at that point nobody can say, but he always felt very close to Eric. The biggest concern that Eric Carr ever had was that Peter Criss might have hated him for taking his place in the band. He didn’t want Peter to think that he usurped him on purpose, or that he didn’t respect what Peter had contributed to the band. When he first met Peter, he said, “I’m so sorry.” It stopped Peter in his tracks. I think he had expected to be defensive around Eric, to try to size him up and convince himself that Eric wasn’t as good a drummer as he was. But he was completely taken aback by Eric’s kindness. Peter speaks fondly of him even today.

Saddened, sobered, we resumed work on

Revenge.

One evening I went to see a group I had produced, EZO, perform in a club. Vinnie Vincent came up to me and apologized for causing the band so much grief while he was a member. He wanted to patch things up and wondered if I would consider writing some songs with him.

Sure, I said. I wanted to let bygones be bygones. I called Paul and told him that Vinnie had apparently changed. Paul wrote songs with him as well. But before the album was released, Vinnie was up to his old tricks again. He reneged on a signed deal we had made and decided that he wanted to renegotiate. He eventually sued us and lost. As far as I was concerned, he was persona non grata forever.

Away from us, he didn’t exactly thrive. He formed a band called the Vinnie Vincent Invasion and signed to Chrysalis Records, but he managed only a couple of records before he was dropped. Actually, the band as a whole wasn’t dropped—Chrysalis re-signed everyone else and renamed the band Slaughter, who then went on to achieve platinum sales. Vinnie then signed a deal with Enigma, but

no record was ever released. People at the label told me that he had erased his own master tapes because he didn’t think the material was good enough. He may have been right.

In 1992

Revenge

came out and did well, going gold. We wanted to go back on tour with Eric Singer and did a series of club dates to introduce him to the faithful fans. Then, we went out on a very successful arena tour—the stage show featured a Statue of Liberty motif. We felt as if Seattle and the grunge bands had killed rock and roll; there was so much bad press for any band that got up onstage to put up a straight show. Grunge killed off the marketplace entirely—there were no lights, no costumes—and by the millions white kids went over to rap, because bands looked like bums. At least rappers were talking about girls and money. A decade later the grunge bands are dead, and the hair bands that they knocked off the map are back with successful summer package tours.

Shannon got pregnant again, and this time it was a girl. By then I had become a full-time father. I had bought roller skates, taken my son for ice cream, and passed on my knowledge. I have pictures of myself as a baby and Nicholas as a baby, and we look like twins. He was a miniature version of me, and in many ways that made the experience easier to handle psychologically. But how would I handle a little girl? How did little girls think? I had so many worries, but all of them evaporated the minute I saw Sophie. I was smitten immediately. She tilted her head to one side, and I was gone.

One of Sophie’s first sentences was, “Daddy, it doesn’t suck.” She was pointing to her bottle. At the age of three she said, “Daddy, can I have a Porsche?” Yes, sweetheart, I’ll buy you a whole fleet of them.

Being a father the second time was just as wonderful, if not more so. The last thing on my mind had been kids—I thought I would die with my freedom. Underneath that, of course, it was all about fear. I didn’t want to run out on my kids when they were six or seven the way my father had run out on me. I wanted to be there. I wanted my kids to know I would always be there for them, and I wanted them to respect me.

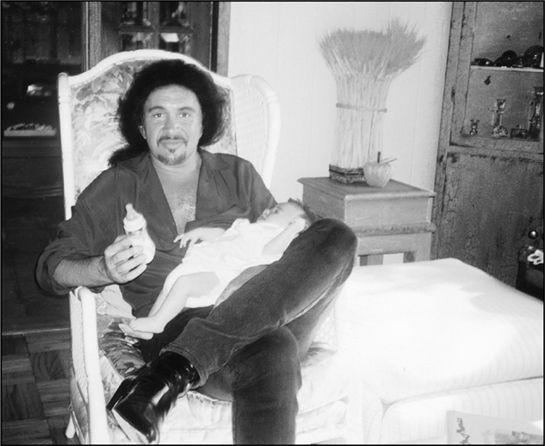

Sophie and me.

Part of gaining that respect was explaining to them how Shannon and I had chosen to live and conduct ourselves as parents. My philosophy was simple: I always felt that in this predetermined world, you should take every opportunity to change things to suit you. If you don’t like your name, pick another. If you want to straighten your hair, straighten it. If you can’t stand where you’re living, move. My kids have both Tweed and Simmons as their last names, but when they get older they will have the chance to keep or change their names.

Shannon and I also tried to clarify our arrangement. As soon as our children were old enough to understand, we explained that we weren’t married, that we were together because we wanted to be. They accepted this, more or less, and where it confused them, we took pains to discuss it at great length. Both Nicholas and Sophie have had classmates and friends whose parents were separated or divorced, and Shannon pointed out to them that this was a painful situation, especially because it required breaking an oath. All in all, I have encouraged them to think of themselves as individuals. When

you create a painting, it has to be original. Don’t paint by numbers. All these metaphors are long-winded ways of saying something very simple: trust yourself to be your own guide.

As I write this book, Nicholas is twelve. Sophie is nine. He didn’t miss a day of school between first and fifth grade and is in advanced studies in sixth grade, as well as having another year of perfect attendance. She constantly earns best student awards. They are wonderful, loving children, and I would do anything for them. I don’t know if life can get better, and they are a large part of why I feel this way. I can see the way they have changed my life every time I visit my mother’s house. I am an only child, remember, and for many years my mother’s house was a shrine to me. You couldn’t find a spot on the wall without a picture of me: here’s Gene eating in a high chair, there’s Gene playing, there’s Gene standing around doing nothing. Now I go over there, and if I’m lucky, I can find a few pictures of me pushed to the back of a table. The rest have been replaced by pictures of my kids. My mother has gone from being the world’s most indulgent, wonderful, loving parent to being the world’s most indulgent, wonderful, loving grandparent.

Sophie at two. I’d do anything for my little girl.

When all the

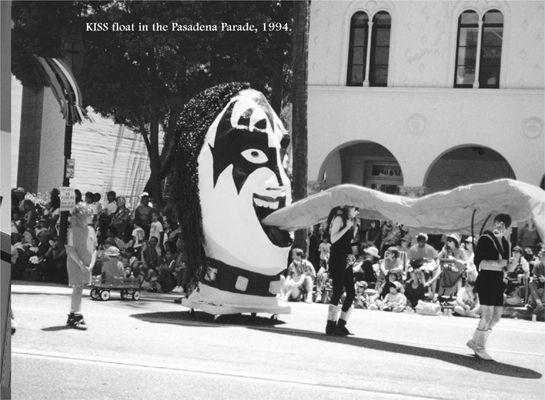

planets line up, you have a chance either to take advantage of it or else miss the opportunity. I had always been aware of our passionate fans, and in the mid-1990s they started holding KISS conventions, in which they got together, dressed up in makeup, and celebrated the KISS experience: not only buying and trading memorabilia but having discussions, showing concert films, and so on. It was a real gathering of the tribe. I read about these conventions and wished I could be there. They had a sense of purpose and togetherness that seemed very genuine, especially in light of all the excess and artificiality we had endured. And then it hit me: we could just hold our own KISS conventions. KISS had

always been about the fans, and we had always been the quintessential American band, of the people, by the people, and for the people. Yet we had grown to the point that we were surrounded by bodyguards and had a moat around the stage. Why didn’t we make ourselves available? Why didn’t we sit up on that stage, answer questions from the heart, and interact with the people who had made us who we were?

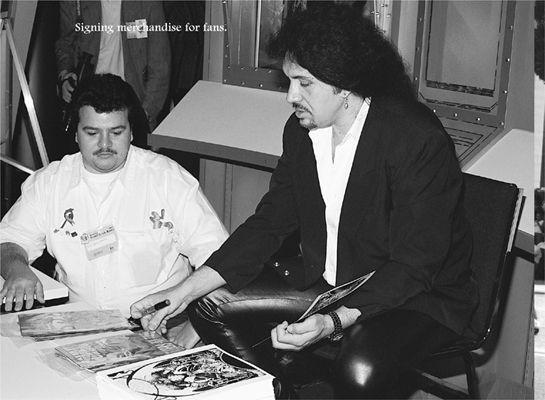

I needed to find someone who could help me make this convention idea into a reality. I had produced two albums by a band named Black ’N Blue, and I went to their guitar player, Tommy Thayer, and sat him down for a heart-to-heart conversation. I told him that his band was not going to make it. I told him that, in my estimation, he had come to a crossroads in his life, and that soon he was going to have to make a choice: he could go into the real world and get a real job, or else he could come work with me. He wanted to know what kind of job I was offering him. I said, “I don’t know. Every day I’ll get up, and I’ll let you know what your job is going to be. And if you’re going to say, ‘I don’t do windows,’ you’d better tell me no now. Because whatever has to be done, including getting the coffee, is what you’ll do. Or else don’t do it.”