Known and Unknown (19 page)

Authors: Donald Rumsfeld

A consequence of my service as director of the CLC was that it put still further distance between Nixon's closest political aides and me. Not being deeply involved in the 1972 campaign, however, turned out to be a considerably bigger blessing than I could possibly have imagined.

Â

A

s the election year heated up, Nixon was heading toward what some political experts said would be a close reelection fight. During much of the prior year, Nixon's job approval rating had hovered at just under 50 percent in the Gallup polls. While I personally liked the eventual Democratic nominee, South Dakota Senator George McGovern, I did not believe he would be a strong candidate for president. I came to know him while I was serving in Congress. He was to the left of the country, and his platform seemed weak. But McGovern did have an advantage, the same advantage Kennedy and Humphrey had had in Nixon's previous contests: He projected warmth.

I wrote a memo for the President, noting that McGovern's “warmth, concern, and decency are appealing.” I suggested that the administration seek opportunities to highlight Nixon's interest in the problems of ordinary Americans. I believed Nixon did care about improving people's quality of life but that he just preferred to view and discuss things in theoretical, rather than personal, terms. That didn't always come across positively in that new media age. “A danger for our administration is that in its competence we seem harsh, in our strength we seem tough, in our pragmatism we seem goal-less and ideal-less.” Finally, I offered a warning, perhaps reflecting concerns I was starting to have about operations at the White House. “The campaign,” I wrote, “must scrupulously avoid going âover the line.'”

19

Even if anyone had listened to that advice, it came a bit late. On June 19, 1972, three days after I sent that memo to the President, the

Washington Post

published a front-page news story with a headline: “

GOP SECURITY AIDE AMONG FIVE ARRESTED IN BUGGING AFFAIR

.”

20

The story linked an attempt to place listening devices at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Hotel to an aide at the Committee to Reelect the President.

21

I attended the regular White House senior staff meeting in the Roosevelt Room that morning.

*

Several expressed curiosity about the piece in the

Post.

There were differing ideas as to how to deal with the article. Some wanted to confront it as a news story that needed to be managedâin other words, as a public relations problem. My instinct was to get to the root of what had happened and get the situation resolved. Years later, Chuck Colson recalled my comment in the meeting: “If any jackass across the street [at campaign headquarters] or here [in the White House] had anything to do with this, he should be hung up by his thumbs today. We'd better not have anything to do with this. It will kill us.'”

22

I don't remember if that was precisely what I said, but if anything that was an understated version of my thinking.

Despite the drumbeat of news stories that began to appear in the

Post

on that subject, the Watergate break-in was not uppermost in voters' minds during the 1972 presidential campaign. However, I did notice troubling signs when the Watergate matter came up in conversations. Joyce and I attended a meeting in the fifth-floor auditorium of the Old Executive Office Building for those Nixon had selected to serve as surrogate speakers for his campaign, including many from his cabinet and key members of Congress, such as Goldwater, as well as Joyce and some other cabinet wives. Ehrlichman offered the group what seemed to me to be tortured responses to some of the questions being raised in the newspapers about Watergate and the campaign. After the meeting I advised Joyce never to repeat Ehrlichman's recommended talking points, because I felt they did not have the ring of truth. Joyce had had the same reaction.

23

Â

T

he Watergate issue proved little more than a nuisance in 1972. Concerns about a close election were misplaced. Nixon won in a landslide, losing only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. His stunning 23 point marginâ60.7 percent to 37.5 percentâwas one of the most decisive presidential victories in U.S. history. The President's reaction to his overwhelming victory was not what most people might have expected. It certainly wasn't what I expected.

The morning after his reelection, Nixon held a cabinet meeting. I assumed the purpose would be to thank everyone for their help in the campaign, and to talk a bit about his goals for his second term.

24

The meeting started off well. Nixon walked into the White House cabinet room to an enthusiastic standing ovation. The President beamed and urged us to take our seats. But the applause continued. For a moment, as he soaked in our congratulations, Nixon paused and gripped the back of his chair in the middle of the large oval table.

Whatever celebratory emotions he may have felt at that moment quickly dissipated. He spoke with his usual precision. He did thank us all for our work, but then quickly moved on to abstract policy discussions. Referring to the most prominent campaign issue, the ongoing conflict in Vietnam, the President said that he had complete confidence that his administration would bring peace. “Richard Nixon doesn't shoot blanks,” he said.

25

He remarked at length on what he said was his favorite period of history, which oddly enough was the British parliamentary debates of the 1850s. He mentioned Winston Churchill's father. “He was a brilliant man,” Nixon said, “whose career was ruined by syphilis.”

He talked about the rival British prime ministers William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli. Gladstone was in office longer, Nixon observed, but Disraeli had a more brilliant record. The President informed us that Disraeli once described Gladstone's government as “an exhausted volcano.” This was a roundabout way for Nixon to make what I took as his central point; namely, that some from his first-term administration were tired. This was a special problem, Nixon added, because second presidential terms usually did not measure up to first terms.

26

Then, to his by now somewhat subdued audience, the President announced he was going to spend the next few weeks on what I knew was his favorite pastimeâthinking about the role each of us would play, if any, in his second term. He said he did not want to be merciless, but that “the government needs an enema.” The President then nodded to his chief of staff. “Bob will take over now,” he said, looking at Haldeman.

27

Nixon left the room to another, considerably more muted, round of applause.

After the President left, Haldeman rather abruptly announced that Nixon wanted everyone's resignation by the end of the week. He said this was customary in a second term, and that Nixon would be making decisions to accept or reject the resignations in the days ahead. He handed each of us an unsigned memo with the subject heading “Post-Election Activities.” It was all very businesslike, as was Haldeman's way.

“While it is recognized that this period will necessarily be a time of some uncertainty,” the memo stated, “this will be dispelled as quickly as possible.” That was not a particularly comforting thought. Nor was what followed. “Between now and December 15, please plan on remaining on the job, finishing first-term work, collecting and depositing Presidential plans, and making plans for next term. This is not a vacation period.”

We were asked to put together a book describing our current assignments, and I sensed that we might well be writing job descriptions for the people replacing us. “This should be as comprehensive as possible,” the memo instructed.

28

All in all the meeting deflated the cabinet's enthusiasm for Nixon's impressive victory. Many of them had worked hard to support the President, and most had served as surrogate speakers. His behavior let down some and angered others. Most everything about itâthe judgment it revealed, the timing, the toneâwas insensitive and unwise.

Immediately after the meeting I told Haldeman he might want to be careful about asking for resignations from anyone at the Cost of Living Council, because almost none of us had wanted to be there in the first place. If we did submit our resignations, we would mean it, and the President would be faced with the problem of trying to manage the economic stabilization programs with a whole new teamâif he could find people willing to do it. I added that he should also be aware that there may be situations like that elsewhere in the administration, where his broad, sweeping request for resignations could boomerang badly. Haldeman came back to me a few hours later, undoubtedly after talking to the President, and said he understood and retracted his earlier request, saying I should not ask for the resignations of those at the CLC.

President Nixon soon departed for Camp David to ponder the upcoming staff shake-ups that had been so indelicately telegraphed.

*

He had his key people with himâHaldeman and Ehrlichman, along with George Shultzâa reassuring sign that Nixon still held Shultz in high esteem. Regrettably, if the President had listened to Shultz more often, and more closely, his second term might have been quite different.

I was ready to leave the administration and had been thinking of going to the private sector. I started consulting with friends back in Chicago about what I might do, and I told Shultz my intentions. As I was deliberating, the President asked me to come to Camp David to meet with him before I made any firm decisions. So in late November 1972, I went up by helicopter, flying north along the Potomac River to the Catoctin Mountain of Maryland, with no idea of what might result from my visit. I met first alone with Shultz and Ehrlichman to give them my thoughts. Then we joined the President in his office for about an hour.

Nixon quickly went to business. He again urged me to run for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois. He told me he would endorse me for the GOP nomination in 1974, even in a crowded primary. Running for the Senate still didn't feel right to me. I had come to understand that I would prefer an executive position more than a legislative role, having by then served in both.

On several occasions, President Nixon and I had talked about the possibility of a foreign policy post. At this meeting, Nixon told me he was going to appoint Elliot Richardson as Secretary of Defense, and that Pete Peterson, the Secretary of Commerce, would probably go to NATO as the U.S. ambassador. As a result, I assumed that the NATO position, which Nixon had discussed with me previously, was out. That had all but decided it for me, since I knew I did not want to remain in the White House.

The President understood that I was starting to move on to other plans. “Don, we will find the right spot,” Nixon assured me as the meeting drew to a close. “To use the chess analogy, I want you to know that you are not a pawn.”

30

A few days later, the Peterson nomination was scratched, and the President informed me he wanted to nominate me to serve as U.S. ambassador to NATO after all. While I knew he had reservations about the way the NATO alliance was functioning, and that Europe hadn't exactly been at the epicenter of his foreign policy in his first term, the President spoke positively of NATO as a good place for me. In one conversation he said that NATO was more interesting and substantive than other ambassadorial posts because it dealt with many countries rather than just one.

31

Because of NATO's collective security approachâan attack on one member nation was to be considered an attack against allâthe alliance had served as an effective deterrent against the Soviet Union. As such, the NATO headquarters in Brussels tended to be a prestigious destination for Europe's most seasoned diplomats. I told the President I would be pleased to be nominated for the post.

The assignment had two important attractions: First it was an opportunity to serve in a new field, and to learn, which I had always enjoyed. Second, I would be out of the White House. My preference to be out of Washington seemed counterintuitive to some. After the public announcement on December 2, 1972,

Washington Post

reporter David Broder wrote: “Much of official Washington was surprised” by my selection.

32

It was true enough that a former congressman from the Midwest who had primarily worked on domestic and economic policy issues might not have been the obvious choice for NATO ambassador.

Others in town, who measured people's power solely in terms of their proximity to the Oval Office, thought I had ruined my career by leaving for Europe right after President Nixon's landslide reelection victory. They could not see why anyone would voluntarily leave the cabinet and the White Houseâthe seat of world powerâto move so far from what they believed to be the center of the universe. But I had worked in two administration posts for close to four years. I had served in the White House and the cabinet, and I was uncomfortable with the thought of staying. I knew the White House was no longer the place for me.

NATO and Nixon's Fall

A

s much as he appreciated the symbolic importance of NATO, Nixon found the alliance frustrating. It operated by consensusârequiring unanimity in any major decisionâand Nixon didn't have a great deal of patience for policy making by committee. Unanimity is hard to achieve in any organization, and it was not easy with a group of the most respected diplomats from fourteen other nations operating on instructions from their capitals, each with different country histories, needs, cultures, and languages, not to mention lingering animosities toward one another after two world wars.

The move to Brussels, Belgium, where NATO is headquartered, turned out to be a treasured experience for our family. But first we had to overcome some initial qualms. Our oldest child, Valerie, was sixteen and had been looking forward to learning how to drive. In Belgium, driver's licenses weren't available until the age of eighteen. So before we left, a friend volunteered to teach her the basics. In our old car with the knob on the floor stick shift missing, Richard B. Cheney kindly and skillfully moonlighted as Valerie's driving instructor in parallel parking.

The neighborhood schools in Belgium taught in French and Flemish. None of them would pass a building code anywhere in the United States. Sharp hooks protruded from walls, the rooms were in disrepair, students were crammed in. Their school, Ãcole Hamaïde, where Marcy and Nick went, emphasized the idea that education was a serious business. Every morning the headmistress, dressed in black and wearing a stern look on her face, would formally shake every child's hand as they entered the buildingâsending the message that it was time to get to work. But at the end of the day, she would bid each of them farewell with a smile and a hug, signaling it was time to have fun again. The school taught responsibility. The students performed the cleaning tasks, not a team of janitors. Joyce and I often have reflected that in that old building our children received what was very likely the best education any of them ever had.

Not all of the aspects of my new post were unqualified advantages. For a time, Joyce and I didn't have a car in Brussels while our car was being shipped over from Washington. As ambassador I had the services of a car and a driver for official business.

I discovered later that someone at the Department of State had sent an agent from the inspector general's office to quiz the embassy drivers about our use of the government car for personal errands. Some at the State Department apparently did not like a political appointee in a post that they felt should be held by a career Foreign Service officer, and they thought that anything they could find that might pose an embarrassment was to their advantage.

1

There had been a pattern of such traps being set for political appointees by some members of the permanent bureaucracies. I first saw this at OEO with the false leak to the press about my alleged office “redecoration.” In Brussels, I also learned later that someone in the Department of State had authorized the building of a swimming pool and a tennis court at the NATO ambassador's residence where we were living. Envisioning a headline about Rumsfeld's efforts to turn the ambassador's residence into a posh resort, I canceled their plans as soon as I learned about them.

M

y predecessor as ambassador, David Kennedy, had served at NATO less than a year, and the post had been vacant for over eight months prior to his arrival. I would be Nixon's third ambassador to NATO. This alone suggested to the alliance that the administration's interest in it was at best modest. In advancing our country's priorities, I knew I was going to need all the help I could get. And I found guidance from what some might consider an unlikely source: the French. In my experience, France's perplexing, and sometimes irritating, public opposition to American policy initiatives seemed more often to be nationalist public relations for the French domestic audience than expressions of real policy differences. Charles de Gaulle, for example, had withdrawn France from NATO's military command structure in 1966 and forced it to take its headquartersâalong with the American and allied forces stationed thereâout of France. The act was more a political ploy than a real demonstration of French independence from NATO. The move infuriated then President Johnson. Johnson instructed Secretary of State Dean Rusk to ask President De Gaulle if his actions toward the forces also meant that we would have to take home all of the American servicemen buried in cemeteries across France who had fought and died for that country's liberation from the Nazis. This was President Lyndon Baines Johnson at his best.

When I arrived at NATO, however, it was clear that the French saw the alliance's value, and wanted a somewhat greater voice in its activities, while still staying apart from the military command structure. I was most fortunate to benefit from the counsel and friendship of the distinguished and seasoned French ambassador to NATO, François de Rose.

The aristocratic François was a delightful blend of intellect, integrity, and good humor. He spoke several languages fluently, including English, which he spoke better than I did. He and his beautiful, vivacious wife, Yvonne, were a generation older and had a vastly more sophisticated lifestyle than the Rumsfelds. Yet we connected and became lifelong family friends. When tensions would flare between the strong-willed Kissinger and the mercurial French Foreign Minister, Michel Jobert, it would fall to de Rose and me to see that their differences did not disrupt our work. In a time-honored diplomatic tradition, François and I frequently resorted to calculated ambiguities that allowed both Washington and Paris to interpret NATO communiqués and declarations as they saw fit.

Â

T

he situation back in Washington was taking on a more ominous tone. On April 30, 1973, the so-called Berlin Wall collapsed at the White House as fallout from the unfolding Watergate scandal: The President had requested the resignations of Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. The

Washington Post

called the resignations “dramatic” and “devastating,” and they certainly came as a shock to me. I knew how central each had been to Nixon personally. Their departures, along with looming criminal charges against both men, foretold what lay ahead. Democrats were now beginning to use the word impeachment publicly.

2

That summer I was amazed to read that President Nixon had secretly taped his conversations in the White House and the Executive Office Building. Nixon apparently believed that recording his every word was a good idea, that it would secure his place in history. It certainly did thatâbut not in the way he intended. I found the secret taping deceitful. All of us offered him candid advice totally unaware that we were being taped, while he, of course, could calculate his remarks.

*

On my periodic trips to Washington on NATO business, I didn't spend much time with the President. By then he was devoting more and more of his hours to his role as the defendant in an impeachment investigation. But I came away with a strong impression that the White House was under siege.

As the scandal grew, our allies began to raise questions about America's increasingly weakened president. Compounding the problem was the fact that the political situations in many NATO countries were also unstable. Some NATO members had government coalitions holding power by twoor three-vote margins in their parliaments. Italy, for example, had already changed governments some thirty-plus times in the twenty-nine years since the end of the World War II. The Netherlands at one point was unable to form a government for many months. With so much political instability in Europe, many there counted on America to be a rock of confidence and reassurance. Now that image was slipping.

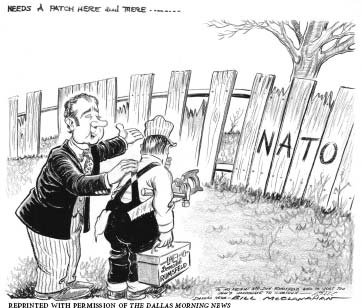

Even the status of the U.S. military in Europe was coming into doubt. In 1973, Democratic Senator Mike Mansfield renewed his effort to remove important portions of our forces from Europe by passing a legislative amendment, which the Nixon administration vigorously opposed. The NATO nations were unlikely to fill any vacuum that would be left by an American withdrawal. Our allies even then were still recoveringâpsychologically, economically, and politicallyâfrom World War II.

â

As a believer in the principle that weakness is provocative, I worried about the signal that a partial withdrawal of American troops from Western Europe would send. It might be seen by the Europeans as the first step in a full withdrawal and, even more worrisome, it could provoke the Soviet Union into taking an even more aggressive posture on the continent. In July 1973, it looked like the legislation might pass, so at the request of the administration I hurriedly flew to Washington to testify against the amendment in Congress.

3

Mansfield's effort was defeated, if narrowly. Though the Senate debate made the Europeans nervous, it might also have had the positive benefit of reminding them that they needed to step up and be more willing to invest in their own defense. Unfortunately, that was a message that many Western Europeans resisted.

Â

O

n October 10, 1973, in a surprise announcement, Spiro T. Agnew resigned as vice president after he was charged with bribery. I had never had a particularly high opinion of Agnew's performance, but even I was startled by the allegations of graft.

Soon thereafter, names began to come up as possibilities to replace Agnew. On Friday, October 12, I was in the ambassador's residence in Belgium when I received a call from a reporter from NBC in Washington. He said he had information that I was going to be named vice president. I thought it was laughable. Then a college classmate of mine, Marty Hoffmann, who was serving as general counsel of the Department of Defense, called and told me the same rumor. After that, we received a dozen or so calls in rapid succession. The BBC said they had it on highly reliable authority that Rumsfeld was to be the nominee. A man from Senator Charles Percy's staff then called and said my name was “all over the Senate.”

4

A media frenzy was now underway, with wild rumors flying around every name suggested by almost anyone. Around 1:00 a.m. in Belgium, Armed Forces Radio reported that another widely mentioned candidate, Gerald R. Ford, was now out of the running. Then CBS, covering multiple bets, reported that the vice presidential nominee would be former Secretary of State Bill Rogers, former Secretary of Defense Mel Laird, or me. I suspected that my name was being thrown into the mix intentionally by Nixon or his staff to either heighten my vis ibility as a possible Senate candidate some day or, more likely, as a diversionâto make his announcement of someone else an even bigger surprise. Convinced it would not happen, I went to bed. Shortly thereafter, two or three cars with press people and cameras arrived and camped out in front of our house. This got Joyce's attention. She nudged me. “Are you sure it's not you?” she asked.

At 2:00 a.m. Brussels time, the cars outside our house started to disperse. In the East Room of the White House, after enjoying the guessing game that had surrounded his choice, President Nixon announced that he intended to nominate House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford to be vice president. I hoped Ford's honesty and forthrightness would help to shake off the ugly mood from Agnew's resignation and the Watergate mess, and reestablish the reputation of the administration.

The vice presidential speculation now over, my attention was on other things. In early October 1973, the Yom Kippur War had broken out. The war began when a coalition of Arab nationsâled by Egyptâlaunched a surprise attack on Israel. As tensions rose, I received a phone call from NATO Secretary General Joseph Luns. The tall and imposing Dutchman was an adept manager of the range of personalities and priorities represented by the fifteen permanent representatives to NATO.

Luns told me he had received a call from the Italian ambassador to NATO, who had received a call from a foreign ministry official in Rome, who had received a call from an Italian senator, who had been called by an alarmed woman in his constituency. The woman had been awakened suddenly by lights and loud vehicle movements at a military facility near her home where American forces were stationed.

5

They all wanted to know what was happening. Like them, I had no idea.