Kokoda (64 page)

Rabbits

were they? Fucking rabbits that had got shot because they were running away, while the clever foxes like Blamey were safely sheltered thousands of miles away? Well cop

this

, mate!

280

Some time later when Blamey and an entourage of his senior officers visited an open-air theatre packed with five thousand Australian soldiers, first one man, then another, then ten more, then seemingly the whole lot of them started booing and whistling in a derisory manner. Once it began there was no stopping it, as their collective rage burst forth in a cathartic release at the brute who caused it. Fearing that it would get completely out of hand, the organisers quickly rolled the movie, whereupon the whistling and cat-calling died down relatively quickly. Hating Blamey was one thing, but getting to watch Betty Grable in

Song of the Islands

quite another.

Back in Sydney, a good while later, Chester Wilmot was not at all surprised to hear of Blamey’s words—he had always detected precisely that aloof yet ignorant attitude in Australia’s most senior military commander. It was one of the many reasons he detested Blamey. Despite Chester’s extreme antipathy, however, after much soul-searching and tossing and turning through the night, Chester had decided to lower himself enough to write a letter of apology to Blamey. He wrote that he was terribly sorry for any misunderstanding there might have been; that he fully accepted that the general had never engaged in any improper activities, and humbly asked that he be reinstated with his accreditation.

It didn’t work. And nor did all the ABC’s representations to Blamey to get him to reverse his decision. In fact, Blamey’s own antipathy remained so strong towards the ABC journalist that before he was done he would try to use the power accorded to him by the Manpower Act not only to get Chester into the army, but also to put him on latrine duty with his own Land Forces HQ, wheresoever they were at any given time.

Despite Blamey’s now well-publicised views of their shortcomings, on 11 November 1942, the Australian forces in the lead on the track finally overwhelmed the Japanese soldiers defending Oivi and moved closer to the Wairopi Bridge over the flooding Kumusi River. Here, though, they started to come up against fresh Japanese reinforcements who had landed and were now stiffening the resistance considerably.

And what of the crack American troops of the 126th Regiment whom MacArthur had unleashed from Kapa Kapa to cut the Japanese off at the pass and block the Japanese retreat at that point? They had done it tough. After forty-two days of stumbling through the jungle where they had seen precisely

no

Japanese soldiers, and fired not a single shot in anger, they indeed made it through. If not to Wairopi as originally intended, they had managed to get to the other side of the Owen Stanleys. Most of them, anyway. Several had died en route from the privations of the jungle—beset by the all too common maladies of malaria, malnutrition and dysentery—while most of the rest had to receive urgent medical attention. As described by the Australian author Jack Gallaway, they became known as the ‘Ghost Battalion’,

281

and were unable to resume any effective action for months after returning.

Not that any of this showed up in MacArthur’s controlled press. Back in Sydney on 9 November 1942, beneath a headline of ‘Enemy Almost Out of Papua: Americans Near Buna’, the

Sydney Morning Herald

reported, ‘American forces have penetrated central and northern Papua to a point near Buna and the Japanese troops defending the strip of land from the Owen Stanley Range to Buna are menaced on several sides… ’

282

Frankly, the Australians who really were there on the ground would have loved to see them. The bottom line was that there were actually

no

Americans fighting alongside the Australian troops as they forced their way to the Kumusi River against a fanatically ferocious Japanese defence. But fight across it the Australians did, and a particularly odd sight greeted them as they did so. There, on the right bank, was the flyblown carcass of a white horse.

In an attempt to ford the flooded river during the retreat after Allied bombing had once again taken out the bridge, General Horii and his steed had been put on rafts that had been hastily constructed by lashing fallen logs together. The horse had fallen from the raft and drowned immediately, while Horii’s fate was still in the balance. After his raft had got caught in a large tree, he and some of his senior officers had transferred to a canoe. In his haste to get back to the main beachhead, Horii decided he would stay with the canoe right down to the mouth of the Kumusi River and then paddle up the coast from there to save time. Though the Japanese general made it to the mouth of the river, once he was in the open sea an enormous storm suddenly hit and neither he nor the senior officers with him were ever seen again. It was the afternoon of 19 November 1942.

283

And finally, it had come to this. The Japanese had now returned to their beachhead at Gona–Sanananda–Buna and were dug in.

Really

dug in. For months the Japanese soldiers who had remained at the beachhead had been preparing these defences, based on crawl trenches joining up carefully constructed coconut log bunkers with thickly made roofs that were placed in mutually supporting positions. For added protection the bunkers had, just within their walls, many 44-gallon drums filled with sand, making them all but impregnable fortresses against mortars and small-arms bullets alike. In some of the most strategic positions, the bunkers had been made out of concrete and steel and all had been built long enough before that the jungle had grown back over them, making them all but impossible to see until you were right upon them. The area so fiercely defended by the Japanese formed a rough triangle, with the Solomon Sea as the long base, the coastal village of Gona at one end and Buna, some twelve miles to the east, at the other end.

It was going to be a brutal task to get the Japanese out, but America’s 128th Regiment and 32nd Division were assigned the primary task of cleaning them out at Buna, and it was for the Australians—led by what was left of Brigadier Ken Eather’s 25th Brigade—to blast them out of Gona.

Beyond the bunkers, trenches and so forth, Gona’s natural defences against an attack were so formidable that a Japanese general would have been proud to call them his own work. A very narrow beach of only ten yards depth gave way to thick groves of coconuts, among which were dotted many banyan trees. This made for a very thick canopy that detonated most of the explode-on-impact shells sent by the Allies way too high to do any damage to anyone sheltered below. On the western edge of the Japanese hold-out, a deep, wide creek also made any attack from that direction out of the question. And on its eastern edge another creek made an attack difficult. On the southern approaches, fetid swamps would effectively catch any attacking force in treacle, preventing them from moving quickly or with stealth. Where there wasn’t swamp, there was either open killing fields of burnt kunai grass, which the Japanese concentrated so much of their firepower on, or thick scrub.

All up it meant that unless the Allies were lucky enough to make a direct hit by a bomb or an artillery shell that penetrated the canopy, the only way to take out the Japs was to find some way through the massacre-maze and sneak close enough to get a well-aimed grenade through the wide slots the Japanese troops used to poke out their heavy and light machine guns—a hairy task. Populating the bunkers alongside the bitterly battle-hardened veterans of the 41st and 144th Regiments were fresh Japanese soldiers brought in from Rabaul.

They were just over a thousand in total, superbly commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Yoshinobu Tomita, who had done for his men much what Ralph Honner had done for the 39th at Isurava. He had organised them so that their arcs of fire supported each other, their ability to move between defensive positions was maximised and every yard of ground gained by the Australians would have to be paid for in blood. Even if any of the Australian soldiers

could

get close to the zig-zagging line of bunkers, Tomita had dozens of snipers up in the thick coconut trees just waiting to pick off Bren gunners and officers in equal measure.

At the Buna end of the battlefront, the Japanese were equally well dug in; not that that fazed the likes of MacArthur. His command of 20 November, ordering the beachhead bastions stormed, was a classic of the genre: ‘All columns will be driven through regardless of losses’. A simple or unthought-through decision by MacArthur, safe in Port Moresby, and dozens of soldiers died in a flash, hurling themselves too hastily at defences that had not been properly reconnoitred. No matter. MacArthur’s orders the next day were more of the same. Directed at his own General Harding, he commanded: ‘Take Buna today at all costs. MacArthur’

.

284

Despite MacArthur’s expectation that once the mighty US Army was involved the Japanese would not be able to hold out for long, it was not to be… After the initial carnage, it barely seemed to matter

what

commands MacArthur made, his men weren’t inclined to advance to their almost certain deaths. Untested in battle, many of these farm boys from Iowa and Idaho had been thrown into one of the toughest theatres of the war and, not surprisingly, were proving to be incapable of effective action.

True, at their end, the Australians had not been making huge advances against the Japanese dug in at Gona—and Brigadier Ken Eather’s 25th Brigade, which had the first crack at them had in fact taken horrendous casualties of 17 officers and 187 soldiers killed— but they were having a go, which was more than could be said for their American counterparts. They, as defined by George ‘Bloody’ Vasey in a letter to Blamey, had ‘maintained a masterly inactivity’.

285

The situation became so bad that in the final week of November, Blamey felt that he simply had to go to Government House to discuss it with MacArthur and his senior staff. The relationship between the Australian general and the Americans by this time had become so strained that the Bataan Gang apparently sometimes privately referred to him as ‘Boozey Blamey’,

286

and it was an antipathy that Blamey himself could not possibly have been unaware of.

This time, though, it was very much Blamey who had the upper hand.

‘It is a very sorry story,’ Blamey told the American general, perhaps with some secret satisfaction at the American’s discomfort. ‘It has revealed the fact that the American troops cannot be classified as attack troops. They are definitely not equal to the Australian militia and from the moment they met opposition they sat down and have hardly gone forward a yard.’

287

When at one point Blamey reported on the appalling casualties that the Australian troops had taken, MacArthur offered the 41st American Division as reinforcements. Blamey pointedly declined, saying he would prefer to get the Australians of the 21st Brigade— now under the command of Brigadier Ivan Dougherty, who had replaced Potts—because, ‘I know they’ll fight’.

288

Just how MacArthur reacted to these words is not recorded, but only shortly after that meeting, the American general summoned one of his most senior commanders in General Robert Eichelberger.

On the broad verandah of Government House, with the vista of Port Moresby harbour spread before them, MacArthur said in a grim voice: ‘Bob, I’m putting you in command at Buna. Relieve Harding. I am sending you in, Bob, and I want you to remove all officers who won’t fight. Relieve regimental and battalion commanders. If necessary put sergeants in charge of companies—anyone who will fight. Time is of the essence. The Jap may land reinforcements any night… I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive.’

289

Plenty of Eichelberger’s men didn’t. For as Eichelberger indeed whipped his men forward without adequate reconnaissance being carried out, or sufficient artillery support to cover them, the fatality rate was appalling.

As to the 21st Brigade, which was once again thrown into the fray to relieve the 25th Brigade—just as the 25th had effectively relieved them at Ioribaiwa—they too did it tough.

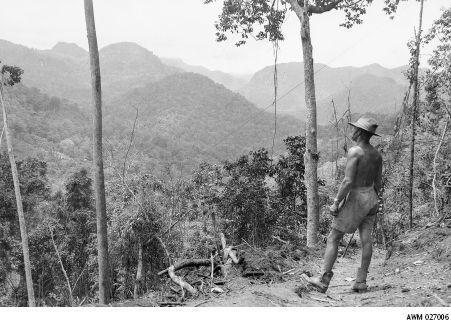

They had flown from Moresby, over those green hills far away, and gazed silently down upon the valleys, ridges and gorges where they had so recently had to fight for their lives. Then just thirty minutes after taking off they’d landed at Popondetta, just a few hours march from Gona, knowing little of what to expect, with the only near-certainty being that there was no way that the coming battle could be any worse than the trials they had known.