Authors: Albert Payson Terhune

Lad: A Dog (4 page)

“Oh Lad! Laddie! I'm so sorry. So sorry! You'reâyou're more of a man than I am, old friend. I'll make it up to you, somehow!”

And now besides the loved hand, there was another touch, even more preciousâa warmly caressing little pink tongue that licked his bleeding foreleg.

, Lady-timidly, adoringlyâwas trying to stanch her hero's wounds.

“Lady, I apologize to you, too,” went on the foolish Master. “I'm sorry, girl.”

Lady was too busy soothing the hurts of her newly dis-, covered mate to understand. But Lad understood. Lad always understood.

2

“QUIET”

TO LAD THE REAL WORLD WAS BOUNDED BY THE PLACE. Outside, there were a certain number of miles of land and there were an uncertain number of people. But the miles were uninspiring, except for a cross-country tramp with the Master. And the people were foolish and strange folk who either stared at himâwhich always annoyed Ladâor else tried to pat him, which he hated. But The Place wasâThe Place.

Always, he had lived on The Place. He felt he owned it. It was assuredly his to enjoy, to guard, to patrol from high road to lake. It was his world.

The denizens of every world must have at least one deity to worship. Lad had one: the Master. Indeed, he had two: the Master and the Mistress. And because the dog was strong of soul and chivalric, withal, and because the Mistress was altogether lovable, Lad placed her altar even above the Master's. Which was wholly as it should have been.

There were other people at The Placeâpeople to whom a dog must be courteous, as becomes a thoroughbred, and whose caresses he must accept. Very often, there were guests, too. And from puppyhood, Lad had been taught the sacredness of the Guest Law. Civilly, he would endure the pettings of these visiting outlanders. Gravely, he would shake hands with them, on request. He would even permit them to paw him or haul him about, if they were of the obnoxious, dog-mauling breed. But the moment politeness would permit, he always withdrew, very quietly, from their reach and, if possible, from their sight as well.

Of all the dogs on The Place, big Lad alone had free run of the house, by day and by night.

He slept in a “cave” under the piano. He even had access to the sacred dining room, at mealtimesâwhere always he lay to the left of the Master's chair.

With the Master, he would willingly unbend for a romp at any or all times. At the Mistress' behest he would play with all the silly abandon of a puppy; rolling on the ground at her feet, making as though to seize and crush one of her little shoes in his mighty jaws; wriggling and waving his legs in air when she buried her hand in the masses of his chest ruff; and otherwise comporting himself with complete loss of dignity.

But to all except these two, he was calmly unapproachable. From his earliest days he had never forgotten he was an aristocrat among inferiors. And, calmly aloof, he moved among his subjects.

Then, all at once, into the sweet routine of the House of Peace, came Horror.

It began on a blustery, dour October day. The Mistress had crossed the lake to the village, in her canoe, with Lad curled up in a furry heap in the prow. On the return trip, about fifty yards from shore, the canoe struck sharply and obliquely against a half-submerged log that a fall freshet had swept down from the river above the lake. At the same moment a flaw of wind caught the canoe's quarter. And, after the manner of such eccentric craft, the canvas shell proceeded to turn turtle.

Into the ice-chilled waters splashed its two occupants. Lad bobbed to the top, and glanced around at the Mistress to learn if this were a new practical joke. But, instantly, he saw it was no joke at all, so far as she was concerned.

Swathed and cramped by the folds of her heavy outing skirt, the Mistress was making no progress shoreward. And the dog flung himself through the water toward her with a rush that left his shoulders and half his back above the surface. In a second he had reached her and had caught her sweater shoulder in his teeth.

She had the presence of mind to lie out straight, as though she were floating, and to fill her lungs with a swift intake of breath. The dog's burden was thus made infinitely lighter than if she had struggled or had lain in a posture less easy for towing. Yet he made scant headway, until she wound one hand in his mane, and, still lying motionless and stiff, bade him loose his hold on her shoulder.

In this way, by sustained effort that wrenched every giant muscle in the collie's body, they came at last to land.

Vastly rejoiced was Lad, and inordinately proud of himself. And the plaudits of the Master and the Mistress were music to him. Indefinably, he understood he had done a very wonderful thing and that everybody on The Place was talking about him, and that all were trying to pet him at once.

This promiscuous handling he began to find unwelcome. And he retired at last to his “cave” under the piano to escape from it. Matters soon quieted down; and the incident seemed at an end.

Instead, it had just begun.

For, within an hour, the Mistressâwho, for days had been half-sick with a coldâwas stricken with a chill, and by night she was in the first stages of pneumonia.

Then over The Place descended Gloom. A gloom Lad could not understand until he went upstairs at dinnertime to escort the Mistress, as usual, to the dining room. But to his light scratch at her door there was no reply. He scratched again and presently Master came out of the room and ordered him downstairs again.

Then from the Master's voice and look, Lad understood that something was terribly amiss. Also, as she did not appear at dinner and as he was for the first time in his life forbidden to go into her room, he knew the Mistress was the victim of whatever mishap had befallen.

A strange man, with a black bag, came to the house early in the evening; and he and the Master were closeted for an interminable time in the Mistress' room. Lad had crept dejectedly upstairs behind them and sought to crowd into the room at their heels. The Master ordered him back and shut the door in his face.

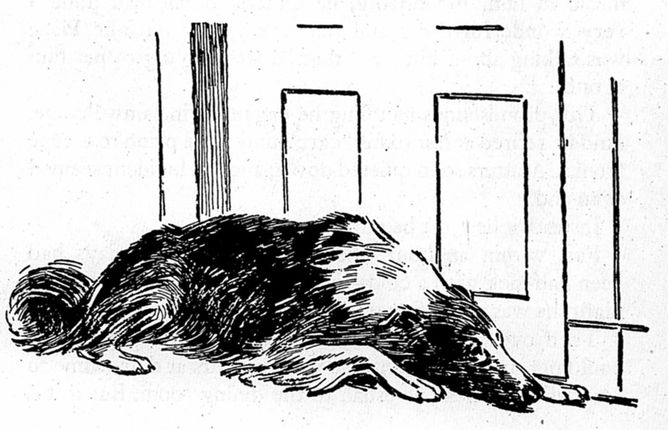

Lad lay down on the threshold, his nose to the crack at the bottom of the door, and waited. He heard the murmur of speech.

Once he caught the Mistress' voiceâchanged and muffled and with a puzzling new note in itâbut undeniably the Mistress'. And his tail thumped hopefully on the hall floor. But no one came to let him in. And, after the mandate to keep out, he dared not scratch for admittance.

The doctor almost stumbled across the couchant body of the dog as he left the room with the Master. Being a dog owner himself, the doctor understood and his narrow escape from a fall over the living obstacle did not irritate him. But it reminded him of something.

“Those other dogs of yours outside there,” he said to the Master, as they went down the stairs, “raised a fearful racket when my car came down the drive, just now. Better send them all away somewhere till she is better. The house must be kept perfectly quiet.”

The Master looked back, up the stairway; at its top, pressed close against the Mistress' door, crouched Lad. Something in the dog's heartbroken attitude touched him.

“I'll send them over to the boarding kennels in the morning,” he answered. “All except Lad. He and I are going to see this through, together. He'll be quiet, if I tell him to.”

All through the endless night, while the October wind howled and yelled around the house, Lad lay outside the sickroom door, his nose between his absurdly small white paws, his sorrowful eyes wide open, his ears alert for the faintest sound from the room beyond.

Sometimes, when the wind screamed its loudest, Lad would lift his headâhis ruff abristle, his teeth glinting from under his upcurled lip. And he would growl a throaty menace. It was as though he heard, in the tempest's racket, the strife of evil gale spirits about to burst in through the rattling windows and attack the stricken Mistress. Perhapsâwell, perhaps there are things visible and audible to dogs, to which humans are blind and deaf. Or perhaps there are not.

Lad was there when day broke and when the Master, heavy-eyed from sleeplessness, came out. He was there when the other dogs were herded into the car and carried away to the boarding kennels.

Lad was there when the car came back from the station, bringing to The Place an angular, wooden-faced woman with yellow hair and a yellower suitcaseâa horrible woman who vaguely smelt of disinfectants and of rigid Efficiency, and who presently approached the sickroom, clad and capped in stiff white. Lad hated her.

He was there when the doctor came for his morning visit to the invalid. And again he tried to edge his own way into the room, only to be rebuffed once more.

“This is the third time I've nearly broken my neck over that miserable dog,” chidingly announced the nurse, later in the day, as she came out of the room and chanced to meet the Master on the landing. “Do please drive him away.

I've

tried to do it, but he only snarls at me. And in a dangerous case like thisâ”

I've

tried to do it, but he only snarls at me. And in a dangerous case like thisâ”

“Leave him alone,” briefly ordered the Master.

But when the nurse, sniffing, passed on, he called Lad over to him. Reluctantly, the dog quitted the door and obeyed the summons.

“Quiet!” ordered the Master, speaking very slowly and distinctly. “You must keep quiet.

Quiet!

Understand?”

Quiet!

Understand?”

Lad understood. Lad always understood. He must not bark. He must move silently. He must make no unnecessary sound. But, at least, the Master had not forbidden him to snarl softly and loathingly at that detestable white-clad woman every time she stepped over him.

So there was one grain of comfort.

Gently, the Master called him downstairs and across the living room, and put him out of the house. For, after all, a shaggy eighty-pound dog is an inconvenience stretched across a sickroom doorsill.

Three minutes later, Lad had made his way through an open window into the cellar and thence upstairs; and was stretched out, head between paws, at the threshold of the Mistress' room.

On his thrice-a-day visits, the doctor was forced to step over him, and was man enough to forbear to curse. Twenty times a day, the nurse stumbled over his massive, inert body, and fumed in impotent rage. The Master, too, came back and forth from the sickroom, with now and then a kindly word for the suffering collie, and again and again put him out of the house.

But always Lad managed, by hook or crook, to be back on guard within a minute or two. And never once did the door of the Mistress' room open that he did not make a strenuous attempt to enter.

Servants, nurse, doctor, and Master repeatedly forgot he was there, and stubbed their toes across his body. Sometimes their feet drove agonizingly into his tender flesh. But never a whimper or growl did the pain wring from him.

“Quiet!”

had been the command, and he was obeying.

“Quiet!”

had been the command, and he was obeying.

And so it went on, through the awful days and the infinitely worse nights. Except when he was ordered away by the Master, Lad would not stir from his place at the door. And not even the Master's authority could keep him away from it for five minutes a day.

The dog ate nothing, drank practically nothing, took no exercise; moved not one inch, of his own will, from the doorway. In vain did the glories of autumn woods call to him. The rabbits would be thick, out yonder in the forest, just now. So would the squirrelsâagainst which Lad had long since sworn a blood feud (and one of which it had ever been his futile life ambition to catch).

For him, these things no longer existed. Nothing existed; except his mortal hatred of the unseen Something in that forbidden roomâthe Something that was seeking to take the Mistress away with It. He yearned unspeakably to be in that room to guard her from her nameless Peril. And they would not let him inâthese humans.

Wherefore he lay there, crushing his body close against the door andâwaiting.

And, inside the room, Death and the Napoleonic man with the black bag fought their “no-quarter” duel for the . life of the still, little white figure in the great white bed.

One night, the doctor did not go home at all. Toward dawn the Master lurched out of the room and sat down for a moment on the stairs, his face in his hands. Then and then only, during all that time of watching, did Lad leave the doorsill of his own accord.

Shaky with famine and weariness, he got to his feet, moaning softly, and crept over to the Master; he lay down beside him, his huge head athwart the man's knees; his muzzle reaching timidly toward the tight-clenched hands.

Presently the Master went back into the sickroom. And Lad was left alone in the darknessâto wonder and to listen and to wait. With a tired sigh he returned to the door and once more took up his heartsick vigil.

Thenâon a golden morning, days later, the doctor came and went with the look of a Conqueror. Even the wooden-faced nurse forgot to grunt in disgust when she stumbled across the dog's body. She almost smiled. And presently the Master came out through the doorway. He stopped at sight of Lad, and turned back into the room. Lad could hear him speak. And he heard a dear,

dear

voice make answer; very weakly, but no longer in that muffled and foreign tone which had so frightened him. Then came a sentence the dog could understand.

dear

voice make answer; very weakly, but no longer in that muffled and foreign tone which had so frightened him. Then came a sentence the dog could understand.

Other books

Secrets (Swept Saga) by Nyx, Becca Lee

4: Witches' Blood by Ginn Hale

Biker Saviour: The Lost Souls MC Series by Hunter, Ellie R

Shepherd's Cross by Mark White

Scorch by Kait Gamble

It's in His Kiss by Caitie Quinn

Too Much Trouble by Tom Avery

The Virgin's War by Laura Andersen

Gambling on a Secret by Ellwood, Sara Walter

Their Solitary Way by JN Chaney