Lamplighter (25 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

Close by a sparrow flitted through the dark from one withered conifer to the next, disappearing into the foliage to twitter from its covert. With a last sharp tweet, it burst out and dashed away, followed by its mate, going southeast up across the roofs of the Low Gutter to disappear over the wall.

“Those things are uncommonly active of a nighttime,” Threnody remarked. “Maybe they’re watchers for the Duke of Sparrows . . .”

Rossamünd started.

How does she know of the Duke of Sparrows?

He turned to stare where the bird had flown to hide his surprise. Were they truly being watched? “How can you know that?” he asked.

How does she know of the Duke of Sparrows?

He turned to stare where the bird had flown to hide his surprise. Were they truly being watched? “How can you know that?” he asked.

“I have heard Dolours say an urchin-lord dwells in the Sparrow Downs,” the girl said smugly, clearly pleased to get a reaction out of him. “The Duke of Sparrows, who she says watches over things and keeps other bogles at bay.”

“What would the Duke of Sparrows have to watch in here?” Rossamünd marveled aloud, his sense of the lay of things shifting profoundly.

“Who can know?” Threnody replied dismissively. “We can’t even be certain such a creature exists. Oh, never-you-mind, lamp boy. Dolours is often quietly telling me things like that: enough to make some people cry

Sedorner

!” She finished with an untoward shout.

Sedorner

!” She finished with an untoward shout.

Rossamünd looked about in fright.

“But I’m not one of those mindless folk,” Threnody concluded, “whatever Mother might insist.”

“Is that why Dolours did not kill the Trought?” Rossamünd said in the smallest whisper.

With a start, Threnody stared at him. “What do you mean, lamp boy?” she demanded.

“I—I would have reckoned she could slay it with one thought, but she just seemed to drive it away—”

“How would

you

know what the Lady Dolours can and can’t do?” Threnody stood tall and arrogant.

you

know what the Lady Dolours can and can’t do?” Threnody stood tall and arrogant.

“Well—I—”

“Bookchild! Vey!” demanded Benedict from the step of the Sally. “Inside at the double! Get to confinations afore the lamplighter-sergeant sees you!”

I hope the Duke of Sparrows

does

exist,

thought Rossamünd as he obeyed the under-sergeant. The notion of a benevolent monster-lord out there seeking to help humans and not harm them was almost too good to be possible.

does

exist,

thought Rossamünd as he obeyed the under-sergeant. The notion of a benevolent monster-lord out there seeking to help humans and not harm them was almost too good to be possible.

13

AN UNANSWERED QUESTION

caladines

also aleteins, solitarines or just solitaires; calendars who travel long and far from their clave spreading the work of good-doing and protection for the undermonied. The most fanatical of their sisters, caladines are typically the most colorfully mottled and strangely clothed of the calendars, wearing elaborate dandicombs of horns or hevenhulls (inordinately high thrice-highs) or henins and so on. They too will mark themselves with outlandish spoors often imitating the patterns of the more unusual creatures that their wide-faring ways may have brought onto their path.

also aleteins, solitarines or just solitaires; calendars who travel long and far from their clave spreading the work of good-doing and protection for the undermonied. The most fanatical of their sisters, caladines are typically the most colorfully mottled and strangely clothed of the calendars, wearing elaborate dandicombs of horns or hevenhulls (inordinately high thrice-highs) or henins and so on. They too will mark themselves with outlandish spoors often imitating the patterns of the more unusual creatures that their wide-faring ways may have brought onto their path.

B

Y the new week all manner of teratologists began to fetch up at Winstermill, braving the unfriendly traveling weather for the prospect of reward—an Imperial declaration

always

held the promise of sous at the end. There were skolds and scourges, fulgars and wits, pistoleers and gangs of filibusters and other pugnators. Some appeared alone, others brought their factotums, and a few swaggerers were served by a whole staff of cogs—clerks and secretaries and other fiddlers of details.There came too the learned folk: habilists and natural philosophers, with their pensive expressions and chests of books. Even peltrymen—trappers and fur traders—answered the call. Bloodless and severe, they arrived from all the wooded nooks, lured from their own perilous labors by the lucrative promises. Every one of these opportunists and sell-swords would come there by foot, by post-lentum, by hired caboose, by private carriage, and stay for a moment and no more than a night, just long enough to gain a precious Writ of the Course. This Imperial document was a guarantee of payment that gave the bearer the right to claim head-money for the slaughter of bogles.

Y the new week all manner of teratologists began to fetch up at Winstermill, braving the unfriendly traveling weather for the prospect of reward—an Imperial declaration

always

held the promise of sous at the end. There were skolds and scourges, fulgars and wits, pistoleers and gangs of filibusters and other pugnators. Some appeared alone, others brought their factotums, and a few swaggerers were served by a whole staff of cogs—clerks and secretaries and other fiddlers of details.There came too the learned folk: habilists and natural philosophers, with their pensive expressions and chests of books. Even peltrymen—trappers and fur traders—answered the call. Bloodless and severe, they arrived from all the wooded nooks, lured from their own perilous labors by the lucrative promises. Every one of these opportunists and sell-swords would come there by foot, by post-lentum, by hired caboose, by private carriage, and stay for a moment and no more than a night, just long enough to gain a precious Writ of the Course. This Imperial document was a guarantee of payment that gave the bearer the right to claim head-money for the slaughter of bogles.

With all these came the usual motley crowd of hucilluctors, fabulists, cantebanks and clowns, pollcarries, brocanders selling their secondhand proofing, even wandering punctographists. Peregrinating, posturing upstarts were coming and going and milling about the manse, some foolishly camping near the foot of the fortress on the drier parts of the Harrowmath. More a nuisance than a novelty, they soon found themselves firmly encouraged to shuffle on to other places.

Yet it was among the teratologists, of course, that Rossamünd discovered the most unusual folk of all. Once in a while there arrived a person dressed in the likeness of an animal or bird, or monster even; and wherever these animal-costumed folk went and whatever they did, they went and did in dance. He recognized something of their prancings in the two calendars who had fought in the Briarywood. At limes, between fodicar drill and evolutions, a pair of these slowly spinning, skipping teratologists danced through the gates on foot, costumed as cruel blackbirds.

“What are they, Threnody?” Rossamünd stared at these, fascinated.

She looked at him as if he were the dumbest boy on watch. “Sagaars, of course!” she answered contemptuously.

Rossamünd stayed dumb.

Threnody narrowed her eyes and wagged her head. “With all those pamphlets you read one would think you’d be sharper, lamp boy,” she continued with a huff. “Sagaars live to be dancing all the day long—some even try it in their sleep—and while they dance they kill the nickers with venomous theromoirs. Several serve my mother and the Right.”

“Like Pannette and Pandomë?”

Threnody hesitated, closing her eyes. “Yes,” she whispered, “like Pannette and Pandomë.”

As these pugnators pranced proud and upset much of the manse’s rhythm, the little varying schedule of prentice life remained. So it went, day come and day go, till Rossamünd was sure the whole of the east must be squeezed full with the monster-wrecking bravoes. As opportunity allowed, he would carefully and keenly review the arrivals, hoping—daring not to admit he hoped—to spy a flash of a deep scarlet frock coat with flaring hems. He could not rightly say why he was so keen to see Europe: he had known her only for the short side of a week, and she was the epitome of deeds he found very hard to reconcile. Regardless, he missed her.Yet with such frequency of arrivings and leavings, such a plenitude of lahzars, Europe, the Branden Rose, was never among them.

By the middle of the week something finally did break the prentices’ routine. The morning was clear and achingly cold; the cerulean sky flat, brilliant, puffed all over with clean white fists of cloud rushed northwest by a whipping wind that was bringing fouler weather with it. The prentices were out and swinging their fodicars about in a tidy and orderly manner, postilion horn-calls an irregular, intermittent music. Teratologists and their attendant gaggles had been steadily coming and going all day. Some would take a turn on the borders of the Grand Mead as they waited for connecting posts or the resolving of kinks of paperwork.

It was limes, and the prentices were formed up and formally sucking on their bitter lemon rinds and sipping tinctured small beer while Grindrod watched to make sure they swallowed it all. This would normally be the time that a quarto would be returning from lighting, had the prentice-watches not been suspended. Rossamünd was considering paying a call on Numps at middens when Benedict marched on to the ground.

The under-sergeant muttered for a moment with Grindrod, then summoned Rossamünd out of file, to the surprise of all the lantern-sticks. Benedict wore an odd expression—somewhere between bemusement and admiration—as he took the young prentice aside. “You have an eminent visitor, prentice-lighter, and have been granted the time to spend with them,” he said officiously, adding in a friendly undertone, “and might I say you keep some odd and powerful company, lad.”

“Who—” Yet before Rossamünd could finish asking he smelled a welcome, well-known perfume drift past. Heart pounding, he spun about. There, in all her healthy bloom, was Europe, the Branden Rose, the Duchess-in-waiting of Naimes, the one who had saved him from a foul end, the one he himself had rescued.

“Well hello, little man,” she said in her silken voice, smiling, amused, maybe even happy to see him. “Still fumbling your way through, I see.”

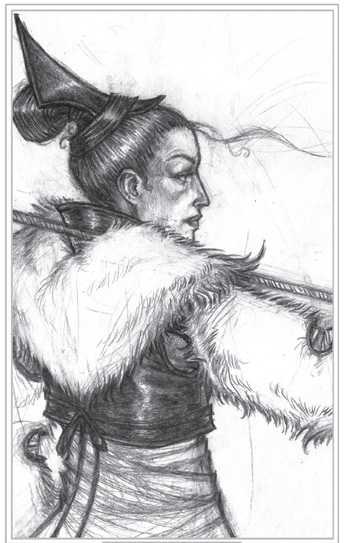

“Hello, Miss Europe.” He could barely manage a hoarse wheeze. It was such a strange sensation to see her familiar face in these now familiar precincts. Her hair was pinned up but without the usual crow’s-claw hair-tine; her deep scarlet frock coat was of another style, made from some kind of short-cropped hide—like the head of a new-barbered lighter—its glossy reds shifting and mottled. Over this she wore a short black pollern-coat with broad collars and sleeves of creamy-hued fur that was faintly spangled at its cuffs with darker spots. Her black boots were trimmed with fur, which made a fuzzy hem at the top of each boot and protruded between the buckles up the sides. This was Europe rugged against the cold.

Rossamünd did not know what to do with himself: some of him wanted to throw his arms about her in sheer delight. The significant part—that part which governs in the end what we really do rather than what we wish we might—was afraid. So he just stood and stared. “You’ve come,” he managed.

EUROPE

The fulgar raised an amused eyebrow. “So it would appear. I have come to knave myself to these kind lamplighters and the citizens of the Placidia Solitus, in so desperate straits they send their pleading bills all the way south to Sinster.” Her face was straight but her voice amused. “What’s a kind-winded girl to do when such plaintive notes are sung?” She was in finer fettle than of their last parting, rosy-cheeked with a shrewd twinkle in her eye. The surgeons of Sinster must have done their infamous work well. “Tell me, little man . . .” Europe leaned forward a little. “Why did you not write me? Did you not miss me?”

“I thought you would be too busy to read any letter of mine, Miss Europe,” Rossamünd answered.

“Why, I do believe he blushes!” Europe laughed. “That young lady certainly watches us keenly,” she said, shifting subjects. “She knows you?”

Rossamünd looked and saw Threnody standing alone on Evolution Green, the other prentices gone now, dismissed for readings. Her arms folded and her face shadowed under the brim of her thrice-high, she was clearly paying Europe and Rossamünd pointed attention.

“Aye, Miss Europe, that’s Threnody. She’s a prentice like me.” Rossamünd attempted a small wave.

Threnody flushed, turned on her heel and marched away without a rearward look.

“A girl as a lighter—how intriguing. I think she might have set her heart on you, little man.”

Rossamünd blushed deeper shades. “Hardly, miss! She’s never happy with anything I say and spends most of her time either ignoring me or huffing and puffing and rolling her eyes. Besides which, she’s older—”

Europe gave a loud peal of honest mirth. “My, my!”

At the start of the Cypress Walk, Threnody turned to the happy, incongruous sound, and Rossamünd was sure she glowered.

Touching the corners of her eyes, the fulgar asked with a smile still in her voice, “And how did she find her way here to vex you so?”

“She was a calendar before, but she has come here to get away from her mother.”

Europe gave a wry smile. “I know how she feels,” the fulgar murmured. “Mothers are best fled . . . Now come along, little man, I have been granted the rest of the day with you by your kindly Marshal. Let us get out of this cold.” She handed him a small, beautifully wrapped parcel. “It is just as well I brought this trifle for you.Your neck is bluer than a wren’s.”

Within the gaudy, fashionably spotted package was a magenta-red scarf made with fine twine.

“It’s tinctured sabine,” the fulgar explained airily. “You can only get it from this one little fellow on the high-walks in Flint. It looks good on you—matches prettily with the harness.”

Other books

A Raucous Time (The Celtic Cousins' Adventures) by Hughes, Julia

The Folly by Ivan Vladislavic

Marrying Money: Lady Diana's Story by O'Connell, Glenys

The Sweetest Thing by J. Minter

Grail Quest by D. Sallen

Alien-Under-Cover by Maree Dry

Viking Ships at Sunrise by Mary Pope Osborne

Unforgettable by Lee Brazil

Mission Road by Rick Riordan