Lamplighter (31 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

“I am told by the clerk-master,” the Marshal continued, “that ye believe yerself to have fought with a homunculid in the ancient tunnels below us. Is this so, prentice?”

“Aye, sir.” Rossamünd swallowed hard. He was about to let the whole tale burble out, when, with a cold stab in his innards, he realized he might betray Numps by telling of the undercroft. With a flicker of a look to the two leers, Rossamünd faltered and went silent.

With this, Laudibus Pile raised his face and, with a dark glance at Sebastipole, fixed Rossamünd with his own see-all stare. It was profoundly daunting to have a twin of falsemen’s eyes—red orb, blue iris—staring cannily from left and right. Rossamünd shifted on the hard seat in his discomfort.

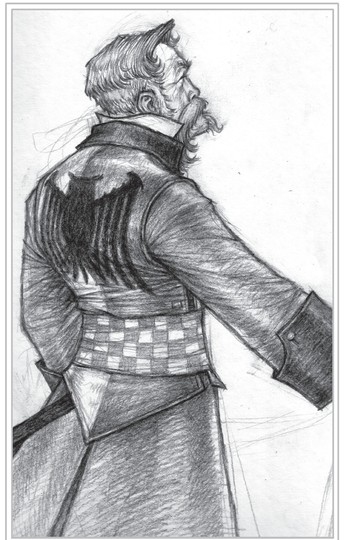

THE LAMPLIGHTER-MARSHAL

“Are ye well, son? I hope that wound does not overly trouble ye,” the Lamplighter-Marshal said, nodding to the thick bandage about the prentice’s head.

“A little, sir.”

“I did my best to mend him, Lamplighter-Marshal,” Swill put in. “It is a nasty cut underneath all that cloth and I am sure, however it was sustained, it is enough to knock the sense out of the boy.”

“So ye said before, surgeon,” the Marshal said gravely. “Tell me, Rossamünd, do ye feel knocked about in yer intellectuals?”

“Somewhat, sir, but I was fully aware before and I am fully aware now.”

The Marshal smiled genially. “Good man.” He shuffled some papers before him. “The good clerk-master has told me his take on yer tale, prentice, and is skeptical. I would like to hear yer own recollection and we shall go on from that. Proceed, young fellow.”

Rossamünd cleared his throat, took a rattling, timorous breath, cleared his throat a second time and finally began. “I had missed douse-lanterns, sir, and found a way under the manse and it took me through all kinds of furtigrades and passages . . .” And so he told of the terrific events, passing very quickly over the how of his presence, avoiding any mention of the bloom baths or Numps, concentrating most on the battle with the prefabricated horror.

All present listened in unmoved silence until his short recounting was finished. Upon its completion the Lamplighter-Marshal nodded gravely and smoothed his mustachios with forefinger and thumb. “I am not a commander who likes to set one fellow’s telling against another’s, yet ye seem a rather slight lad to be the conqueror of so fearsome a thing as a rever-man. More than this is how such a beastie ever won into places no monster has ever made it to before. How-be-it, my boy, ye were the only one present and my telltale finds no fault with yer summation.”

Rossamünd had not been aware of any communication between the Marshal and the lamplighter’s agent, yet somehow Sebastipole had made what he observed clear to the Lamplighter-Marshal.The leer gave a barely perceptible nod to the prentice. “Indeed, sir, what he has told us has contained no lie.”

He believes me after all!

Rossamünd could have done a little caper for joy, but kept still and somber.

Rossamünd could have done a little caper for joy, but kept still and somber.

Laudibus Pile darted a calculating, ill-willed squint at Sebastipole.

“As it is, this is a most difficult situation, prentice.” The Lamplighter-Marshal became very stern. “Ye have placed me in a bind, for on the one hand ye must be applauded—surely awarded—for yer courage and sheer pluck at prevailing in such a mismatched contest as ever a fellow was set to.”

Rossamünd’s heart leaped with hope.

“Yet,” the Lamplighter-Marshal went on firmly, “the circumstances surrounding yer feat of arms are drastically irregular, would ye not agree, lad? To be out beyond douse-lanterns though not of the lantern-watch or the night-watch is a grave breach. Entering restricted parts of the manse, another grave breach. Perhaps we should simply all be glad for the blighted thing’s destruction. But a rule for all is a rule for one, and a rule for one is a rule for all, do ye agree, Prentice Bookchild?”

The prentice swallowed hard. “Aye, sir.” Though he had never heard entering the underregions of Winstermill formally proscribed, this revelation did not surprise him—most things were out-of-bounds for a prentice.

The Master-of-Clerks stirred. “If I may interject here, most honored Marshal, with the observation that my own telltale does not find all particulars of the prentice’s retelling wholly satisfying.”

With a single, stiff nod, Laudibus Pile confirmed his master’s claim.

“When falsemen disagree, eh?” The Lamplighter-Marshal became even sterner, hard, almost angry—with whom, Rossamünd could not tell, and he swallowed again at the anxiousness parching his throat.

“In fact, sir,” the Master-of-Clerks pressed, “I might go so far as to state that one does not need to be a falseman to detect the irregularities in this . . . this one’s story. Perhaps your telltale does not see it so clearly? I am rather in the line that this little one is just grasping for glories to cover his defaulting.” He bent his attention on Rossamünd. “You have waxed eloquent upon your fight with the wretched creature, child, and the proof that you came to blows with

something

is clear; but I still do not follow how it is that

you

came to be in the passeyards at all or why it is that your journey took you to my very sanctum? You avoided the question before, but you shall not do so now.”

something

is clear; but I still do not follow how it is that

you

came to be in the passeyards at all or why it is that your journey took you to my very sanctum? You avoided the question before, but you shall not do so now.”

“The passeyards, sir?” Rossamünd asked.

“Yes.” The Master-of-Clerks flurried his fingers impatiently. “The interleves, the cuniculus, the slypes—the passages twixt walls and beneath halls, boy!”

“Oh.”

The Lamplighter-Marshal raised his right hand, a signal for silence, stopping the Master-of-Clerks cold. “Yer point is made, clerk-master. Prentice Bookchild, ye have a reputation for lateness, do ye not? As I understand it, ye have gained the moniker ‘Master Come-lately,’ aye?”

“Aye, sir.”

“But, as I have it, ye do not have a reputation for lying, son, do ye?”

“No, sir.”

“So tell us true: how is it ye found such well-hidden tunnels as those ye occupied tonight?”

Ashamed, Rossamünd dropped his head then darted a look to the Marshal, whose mild attentive expression showed no hint of his thoughts or opinion. “I was with the glimner, Mister Numps, down in the Low Gutter, and I forgot the time so—so I went by the drains so I could get into the manse after douse-lanterns.” He was determined not to implicate Numps in any manner, but with a falseman at both sides, it was an impossible ploy. Yet Rossamünd was desperate enough to attempt to dissemble. “I found them . . . through . . . through somewhere under the . . . the Low Gutter, sir—”

Laudibus Pile’s glittering gaze narrowed. “Liar!” the falseman hissed caustically.

“Ye will address an Emperor’s servant with respect, sir,” the marshal-lighter pronounced sharply, “be he above or below ye in station!”

“He does not lie, Pile!” Sebastipole added grimly.

“He dissimulates!” Laudibus snapped, with a black look to the Marshal then his counterpart.

“Indeed he might,” Sebastipole countered smoothly, “but he does not lie.”

“Enough, gentlemen!” The Marshal cut through, and there was silence. He returned his attention to Rossamünd. “Now, my man, whitewashing tends only to make one look guilty. Say it straight: we only want to find how this gudgeon-basket got into our so-long inviolate home, and so stop it happening again.Where did ye gain entry into the under parts?”

“Through the old bloom baths.” Rossamünd dropped his head, feeling the most wretched blackguard that ever weaseled another. “Under the Skillions, where they once tended the bloom.” He did not mind trouble for himself near half as much as implicating Numps.

The Marshal just nodded.

“What old bloom baths?” asked the Master-of-Clerks sharply, forgetting his place perhaps, interrupting the Marshal’s inquiries. “How, by the blight, did you find such a place on your own? A place, I might add,” he continued with the barest hint of a displeased look to the Marshal, “that

I

have only heard of tonight! You cannot expect us to believe you discovered such a place in solus!”

I

have only heard of tonight! You cannot expect us to believe you discovered such a place in solus!”

“In solus, sir?”

“By yourself,” he returned tartly. “Who showed you where they are?”

“I—” Rossamünd did not know how to answer.

“Speak it all!” Laudibus Pile spat.

“Silence!”

barked the Lamplighter-Marshal. “Another gust from ye, sir, and ye

will

be exiting these rooms!”

barked the Lamplighter-Marshal. “Another gust from ye, sir, and ye

will

be exiting these rooms!”

An undaunted, cunning light flickered in the depths of Pile’s eyes, yet he yielded and seemed to retreat deeply within himself.

After an uncomfortable, ringing pause, the Master-of-Clerks fixed the prentice with his near-hungry stare. “You must tell us, prentice,” he said softly, “how then do you know of such a place?”

“It is common enough knowledge that there are ancient, seldom visited waterworks and cavities underneath our own pile, sir,” came Sebastipole’s unexpected interjection.

“I think, Master-of-Clerks,” was the Lamplighter-Marshal’s firm and timely addition, “that ye may leave this line of questioning now. The boy has been brought up short enough with the night’s ordeal

ipse adversus

—standing alone! What is more, it brings no clarity to the more troubling details.”

ipse adversus

—standing alone! What is more, it brings no clarity to the more troubling details.”

The Master-of-Clerks became a picture of pious obedience. “Certainly, sir,” he returned respectfully, smoothing the gorgeous hems of his frock coat. “I am just troubled that the existence of those old bloom baths is what has allowed the creature—if such exists—to find its way in. If that be so, then we will most certainly have to do away with the whole place,” the Master-of-Clerks declared officiously, “to be thorough.”

From across the Marshal’s desk Rossamünd could see the tension in Sebastipole, the lamplighter’s agent’s jaw tightening, loosening, tightening, loosening with rhythmic distraction.

“But the rever-man was shut up in some old room a long way from the bloom baths,” the young prentice dared.

“So you say, child.” The Master-of-Clerks smiled serenely at Rossamünd, a sweet face to cover sharp words. “Yet if a mere prentice can find his way so deep in forgotten places, then why not some mindless monster, and these unvetted baths may well be the cause.”

The Lamplighter-Marshal raised his hand, stopping Podious Whympre short. “There is no need and nothing gained from despoiling those old baths,” he said firmly. “They have been here for longer than we, and are buried deeply enough, and no harm will come from the quiet potterings of faithful, incapacitated lighters.”

“You already know of it, sir?” the Master-of-Clerks replied with a studied expression. “This—this continued unregistered, unrecorded activity? Why was I not informed . . . sir?”

“I do know of it, Clerk-Master Whympre,” the Marshal replied, “and I iterate again it is not the case of most concern. I could well ask ye how it is that there is a way down from yer own chambers into these buried levels.”

The Master-of-Clerks blanched. “It is a private store, sir. I had no idea it connected to regions more clandestine,” he explained quickly.

Other questions continued. Rossamünd felt unable to answer any of them to full satisfaction: did he have any inkling of where the gudgeon had come from?

No, sir, he did not. It had, by all evidence, been locked in the room rather than having arrived from somewhere. In the end he simply had to conclude that he truly had no idea of the how or the why or the where of the gudgeon’s advent.

Did he recognize where he found the gudgeon?

No, sir, he did not.

Would he be able to find the place again—or give instructions to another to do the same?

Rossamünd hesitated; he could only do his best, sir. He described his left-hand logic to solving the maze and as much of the actual lay of the passages and the rest as he could recall.

And all the while the Master-of-Clerks was looking at him with his peculiar, predatory gaze. Pile seemed to sulk, and said nothing.

“I will look into this, sir,” Sebastipole declared. “Josclin is still not well enough; Clement and I shall take Drawk and some other trusty men and seek out this buried room.” With that the lamplighter’s agent left.

“If you could excuse me, Lamplighter-Marshal.” Swill stood and bowed. “I must attend to pressing duties,” he said with a quick look to Sebastipole’s back.

“Certainly, surgeon,” the Marshal replied. “Ye are free to go—and ye may depart too, clerk-master. Yer prompt action is commendable.”

“And what of this young trespasser?” The Master-of Clerks peered down his nose at Rossamünd. “I hope you will be taking him in hand.Whatever other deeds might or might not surround him, you cannot deny that he has contravened two most inviolate rules, and it is grossly unsatisfactory that he has violated my own offices.”

“What I do with Prentice Bookchild is between him and me,” the Marshal returned firmly. “Good night, Podious!”

With a polite and contrite bow the Master-of-Clerks left, his telltale and the surgeon following.

Grindrod was admitted in their stead, hastily dressed and looking slightly frowzy.

Other books

Who's Sorry Now? by Jill Churchill

The Shipmaster's Daughter by Jessica Wolf

The Lunatic's Curse by F. E. Higgins

Candi by Jenna Spencer

Fourth Victim by Coleman, Reed Farrel

Marilyn by J.D. Lawrence

The Spymaster's Daughter by Jeane Westin

Deadly Nightshade by Daly, Elizabeth

Sempre: Redemption by J. M. Darhower

To Your Scattered Bodies Go/The Fabulous Riverboat by Philip José Farmer