Lamplighter (32 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

“Ah, Lamplighter-Sergeant!” the Marshal cried. “Ye seem to have been missing one of yer charges, but here I am returning him to ye.”

“Aye, sir.” Grindrod stood straight and, appearing a little embarrassed, gave Rossamünd a quick yet thunderous glare. “Thank ye, sir.”

“Not at all,” the Marshal answered. “Ye make fine lampsmen, Sergeant-lighter. This young prentice has been doing the duties of a lamplighter even as his fellows sleep. Return him to his cot and set a strong guard over his cell row. Fell doings have been afoot. We shall discuss his deeds after.”

The lamplighter-sergeant looked stunned. “Aye, sir.” Thunder turned to puzzled satisfaction.

“Our thanks to ye, Prentice Bookchild,” the Lamplighter-Marshal said to Rossamünd. “Yer part here is done; ye played the man frank and true.Ye may turn in to yer cot at last. Be sure to report to Doctor Crispus tomorrow morning. Good night, prentice.”

With that the interview was ended.

Rossamünd left under the charge of Grindrod, feeling a traitor. While he was sent to sleep, he was aware of a growing bustle about as the soldiery of the manse were woken up to defend it from any other rever-men that might emerge from below.

“I don’t know whether to castigate or commend ye, young Lately!” the lamplighter-sergeant grumped as he led the prentice along the passages. “Just get yer blundering bones to yer cot and I’ll figure a fitting end for yer tomorrow.”

For another night Rossamünd readied himself in the cold dark and slept with his bed chest pulled across the door to his cell.

17

HASTY DEPARTURES

sis edisserum

Tutin term, loosely meaning “please explain”, this is an order from a superior (usually the Emperor) to appear before him and a panel of peers forthwith to offer reasons, excuses, evidence, testimony and whatever else might be required to elucidate upon whatever demands clarity. A sis edisserum is usually seen as a portent of Imperial ire, a sign that the person or people so summoned are in it deep and must work hard to restore Clementine’s confidence. A sis edisserum is a “black mark” against your name, and very troublesome to remove.

Tutin term, loosely meaning “please explain”, this is an order from a superior (usually the Emperor) to appear before him and a panel of peers forthwith to offer reasons, excuses, evidence, testimony and whatever else might be required to elucidate upon whatever demands clarity. A sis edisserum is usually seen as a portent of Imperial ire, a sign that the person or people so summoned are in it deep and must work hard to restore Clementine’s confidence. A sis edisserum is a “black mark” against your name, and very troublesome to remove.

R

OSSAMÜND awoke with the worst ache of head and body that he had ever known and his bladder fit to burst. He hurt like the aftermath of the most severe concussion he had ever received in harundo practice. For a time he could not remember much of yesterday, though a lurking apprehension warned him the memory would be unwelcome. With the sight of his salumanticum discarded on the floor and the bed chest blocking the door recollection struck. A gudgeon . . . a gudgeon in the forgotten cellars of the manse, right in the marrow of the headquarters of the lamplighters! A monster loose in Winstermill!

OSSAMÜND awoke with the worst ache of head and body that he had ever known and his bladder fit to burst. He hurt like the aftermath of the most severe concussion he had ever received in harundo practice. For a time he could not remember much of yesterday, though a lurking apprehension warned him the memory would be unwelcome. With the sight of his salumanticum discarded on the floor and the bed chest blocking the door recollection struck. A gudgeon . . . a gudgeon in the forgotten cellars of the manse, right in the marrow of the headquarters of the lamplighters! A monster loose in Winstermill!

He dragged back the chest and opened the door to find Threnody there, leaning on the wall as if she had been waiting.

“You missed the most extraordinary pudding at mains last night,” she said dryly. Evidently she had elected to speak to him again.

“Aye . . .” Rossamünd knew by “extraordinary” she did not mean “good.” Threnody had always hated the food served to the prentices, and the new culinaire was achieving new acmes of inedibility.

“You might be a poor conversationalist,” she continued as they went to morning forming, completely heedless of the thick bandage about his head, “but at least you’re interesting. Between Arabis having the others ignore me, and Plod mooning and staring all through the awful meal, it was a very long evening.” She peered at him. “Where’s your hat?” But by then Grindrod was shouting attention and all talk ceased.

In files out on the Cypress Walk it was obvious the manse was in a state of agitation, with the house-watch marching regular patrols about the Mead and the feuterers letting the dogs out on leads to sniff at every crevice and cranny. Under a louring sky the atmosphere of the fortress was tense and watchful.

“Do

not

be distracted by all this hustle ye see today, lads,” Grindrod advised tersely. “There was an unwelcome guest in our cellars last night, but the rotted clenchpoop is done in now.” He looked meaningfully at Rossamünd. “Just attend to yer duties with yer regular vigor.”

not

be distracted by all this hustle ye see today, lads,” Grindrod advised tersely. “There was an unwelcome guest in our cellars last night, but the rotted clenchpoop is done in now.” He looked meaningfully at Rossamünd. “Just attend to yer duties with yer regular vigor.”

At breakfast the other prentices stared openly at Rossamünd’s bandaged head.

“How’s it, Lately?” asked Smellgrove as Rossamünd sat down with his fellows of Q Hesiod Gæta. “Is the bee’s buzz true?”

“What buzz?”

“That you came to hand strokes with a gudgeon last night,” said Wheede, pointing to Rossamünd’s bound noggin.

“Ah, aye, it nearly ruined itself trying to destroy me.”

“Pullets and cockerels!” said several boys on either side.

Insisting others shift to make room, Threnody sat next to him. “Have any of you others fought one before?” she asked knowingly.

Universal shakes of the head.

“Because I can tell you,” she boasted, “that a full-formed lamplighter would struggle to win against one, let alone a half-done lamp boy.”

“I have heard it that wits can’t do much to them either.” This was Arabis, listening at the far end of the bench.

Threnody lifted her chin and pretended she had not heard him.

“Tell us, Rosey,” asked Pillow, “how did you do the thing in?”

“I burned the basket’s head out with loomblaze!” Rossamünd said, with more passion than he intended. “It went smashing down through the stair into the pits deep underneath.”

There was an approving mutter of amazement.The looks of awe turned Rossamünd’s way were simultaneously intoxicating and hard to bear. He ducked his head to hide his confused delight, but one incredulous snort from Threnody and his small, uncommon joy was obliterated in an instant.

After breakfast Grindrod did not say any more about Rossamünd’s yesternight excursions. However, he did seem to address Rossamünd with a touch more dignity as he sent him to Doctor Crispus for further examination. “Ye may take yer time, Prentice Bookchild: well-earned wounds need proper treating.”

“Cuts and sutures, my boy, you certainly have a bump and a gash upon your scalp to show for some kind of scuffle,” the physician declared as he cleaned the nasty contusion on Rossamünd’s hairline and rebandaged it.

“Swill tried to recommend callic for me last night,” Rossamünd said pointedly.

Crispus wagged his head in disapproval. “Fumbling butchering novice,” he said, clucking his tongue. “Even a first-year tyro would know callic is not for concussions. By your current alertness I can assume he did not succeed in his fuddle-brained prescription?”

“No he did not, Doctor. I know enough of the chemistry to have not taken any even if he had.”

“My apologies, Rossamünd. He certainly is not who I would have here,” Crispus complained. “But the young quackeen is only nominally under my authority; rather he answers to the Master-of-Clerks himself. Very unsatisfactory, and a clear nuisance when he comes a-quacking in my trim infirmary.” He clucked his tongue again. “A mere articled man strutting about as if he is a senior surgeon.”

“He certainly reads some strange books for a surgeon,” said Rossamünd.

“Does he, indeed?” Crispus blinked owlishly.

“Aye, sir.” Rossamünd squinted at the ceiling in recollection. “Dark books, from what my old Master Craumpalin told me.”

“Where did you see these, child?” the physician pressed.

“In Swill’s apartment, way up in the manse’s attics. Mother Snooks sent me up the kitchen furtigrade, delivering a pig’s head to him.”

“The kitchen furtigrade?” Crispus looked utterly amazed. “I did not know one existed, though Winstermill is old enough to have a thousand such obscure places. You certainly have had a tour of the slypes, haven’t you?”

“And the attic apartment?”

“Oh, that place is just his personal library, a place of private reflection. ‘Do not disturb’ and all that. I’ve never begrudged him this: a professional man must have his sanctuary for study—I have one of my own. In our profession there are some strange tomes—some better had we never read them, of course. And as for the pig’s head—well, a surgeon must practice his sutures, I suppose.”

Rossamünd was unconvinced.

Sebastipole entered the infirmary and, after asking of Rossamünd’s health, went on to request a personal word.

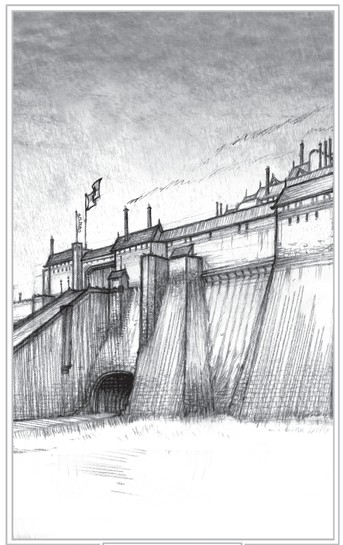

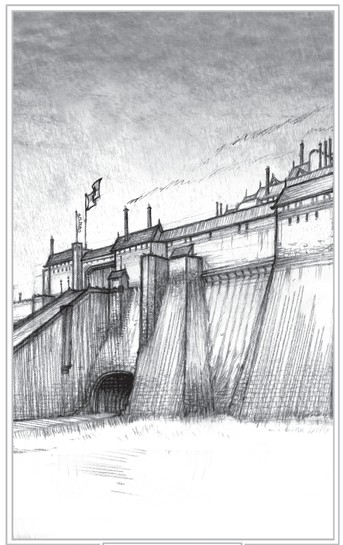

WINSTERMILL

The dressing of the wound complete, Crispus left them and attended to other patients.“Did you find anything in the tunnels, Mister Sebastipole?” Rossamünd asked eagerly but in a low voice.

“There was no gudgeon corpse,” the leer answered.

Rossamünd’s soul sank.

“And all that was left of the stair was splinters and wood-dust,” Sebastipole went on.

Rossamünd’s dismay deepened. His desperate struggle must have wrenched the ancient furtigrade too much.

“I have heard of gudgeons so cunningly made they dissolve into a puddle after they expire,” Sebastipole expounded further. “Do not worry, Rossamünd, you are believed,” he added, seeing the young prentice’s dismay. “But I must tell you it was touch and go to even find your path; we found our way more by your instructions than your trail.Were you using a nullodor last night at all?”

Rossamünd felt a caustic flush of guilt, as if he had been caught out. “You can smell a nullodor?” He had no reason to feel this, yet he did.

“Actually, no: they do their job just as they should—all smells gone where applied. It is rather that absence of scent that is the telltale signifer. Think of it like reading a letter where a clumsy author has cut out his errors with a blade and as you read there are great holes in the sentences.You know something was there but you’d be hard-pressed to say what it was.” Sebastipole sniffed, then blew his nose. “Such a ruse will work against a brute beast but not against the pragmatical senses of a well-learned leer.” He looked at Rossamünd searchingly.

“Oh,” the young prentice said in a small voice, “and there were no smells down there?”

“Exactly so.” The leer’s expression was impenetrable. “The whole area was a great blank, with only the merest suggestion of many obliterated smells. If you pressed me I might say that more than one nullodor was employed, but it is too hard to prove so now.”

“Oh . . . I am sorry, Mister Sebastipole,” Rossamünd murmured. “My . . . my old masters have me wearing a little each day . . . to keep me safe, they said, from sniffing noses.” He could not see the sense in hiding it now.

“Indeed?” The leer looked astutely at him, held him with a silent, penetrating regard. “I detected a nullodor on you the night we went out lighting together.”

Rossamünd ducked his head and blushed. “My old masters are very protective of me.”

“And you are very obedient to

them

, it would appear.”

them

, it would appear.”

Rossamünd nodded sheepishly.

Sebastipole smiled. “Yet, Rossamünd, I

did

manage to detect the merest smell of your foe. It was exactly like the foreign, foul slot of Numption’s attackers.”

did

manage to detect the merest smell of your foe. It was exactly like the foreign, foul slot of Numption’s attackers.”

“What does that mean, sir?”

“I have not encountered enough gudgeons to know beyond doubt, but the similarity seems suspicious to me. It may well mean the creature that beset Numption and that which you slew last night—though separated by three years or more—have come from the same benighted test, made by the same black habilist. If that is so, the wretch has grown arrogant enough to try his constructions on us again!” The anger in Sebastipole’s eyes was made more terrible by their unnatural hue. “More galling still, we did not find how the homunculid found its way in. Others could come.”

Rossamünd’s imagination fired with the abhorrent scene of the fortress overrun with rever-men.

“Hmm.” The leer became ruminative. “I can say that it certainly did not come from the region of Numption’s bloom baths.”

“I did not want to tell about them,” Rossamünd confessed forlornly.

“I know you did not, Rossamünd.” The leer spoke up quickly. “You are an honest fellow and your honesty last night made proceedings easier. Fret not for dear Mister Numps: he is protected, and his ‘friends’ with him. I asked him to let us in and only took those with me who would treat him kindly.”

Other books

Shadow Traffic by Richard Burgin

Hare Sitting Up by Michael Innes

Cure for the Common Universe by Christian McKay Heidicker

Charles the King by Evelyn Anthony

Chocolate Cake for Breakfast by Danielle Hawkins

Scrubs Forever! by Jamie McEwan

The Fun Parts by Sam Lipsyte

Forgotten Forbidden America: Rise of Tyranny by Thomas A Watson

Bassist Instinct (The Rocker Series #2) by Vanessa Lennox

What's Better Than Money by James Hadley Chase