Last Days of the Bus Club (9 page)

Read Last Days of the Bus Club Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

F

EW EXCITEMENTS IN LIFE CAN COMPARE

with finding a new-laid egg nestling in the bright golden straw of a corner of the hen house. I’ve yet to meet a child unmoved by such a discovery, and even for adults, like myself, it’s pretty good. I would argue that the contemplation of the aesthetic beauty of an egg – the very acme of perfection and, if you happen to be an alligator, a turtle or a chicken, the cradle of existence – transports us to thoughts of the sublime.

The finest way we can express this is by elaborately preparing them for our consumption. And of all the wonderful ways there are, you can do no better than fry them. An egg fried in hot, deep spitting olive oil with the brown, crispy bits around the edges and the rich

deep-yellow

yolk still liquid but with just a hint of viscosity and barely covered with a pale film of heated albumen … well, this is about as near an approximation of felicity as you can get. Scrambled eggs come hot on the heels of the fried ones, and it’s a marvellous way to get rid of a glut of eggs. Two of

you ought to be able to deal with five of them. Make perfect golden toast and put it on a plate. If you live north roughly of the 45th parallel, then you’ll want some butter on the toast; anywhere south of that and you’re better off with olive oil. Break four of the eggs in a bowl and just the yolk of the fifth; this makes it a bit yellower. Beat ’em up a bit and tip into a pan in which you have heated some butter and oil. Cook slowly and don’t stop stirring with a wooden spoon even for a minute. Take the pan off the heat while the eggs are still shiny and runny; they’ll keep on cooking. Tip the mix onto the toast and shave with a potato peeler some smoked cod’s roe on top, a hint of tabasco and a big pinch of pepper and maybe a peck of parsley.

Now what you need for eggs is, of course, chickens. Unfortunately at El Valero we had lost the chickens when the chicken-run wall collapsed and the fox got in and wolfed – in a manner of speaking – the lot. Ana and I were desolate, and we felt the impact of this loss all the more acutely when Chloé left home at the start of the university term to move into a flat in Granada. If getting Chloé up and out to catch the school bus was the great imperative that got us rolling in the morning, then feeding the chooks ran it a close second and for a time we lived a rudderless existence.

Added to this, we had no reason now to save the scraps of food that we used to put aside so assiduously, knowing that they were not mere leftovers but tasty ingredients of a future meal. It takes a lot of the fun and dash out of cooking when you know there’s no margin left for error; no chickens to polish off the unpalatable bits, the failed experiments or the portions excess to requirements that remain in the bottom of the pan. It offended our frugal country habits and natural inclination towards recycling, but most of all it

pained us that we had no eggs to send to Chloé, who, having shown little interest in farm produce while living at home, had developed a passion for home-grown fruit and

vegetables

as soon as she moved away. She was on a mission, she told us, to buck up her flatmates’ ideas about healthy eating and impress upon them the sound economy of relying on nature’s own larder rather than waste good partying money on the ready-made muck sold at the local

supermercado

.

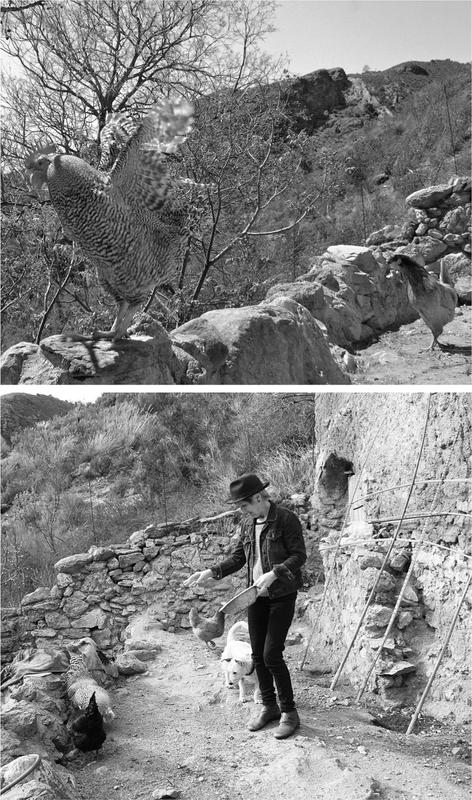

To return to our chicken-led way of life, I needed to repair their run, and this time it would have to be the sort of run that would last them, and us, for the rest of our days. Time was marching on and the last thing I wanted to be doing in ten years’ time was to start all over again on the poultry. A good solid chicken run ought to take the place of the pensions and insurances that we have always seen fit to avoid.

So I built the chicken run and I built it well, adopting a nice compromise between art and fortification. The next step was to people it with chickens. Quite by chance, Ana had come across a superlative poultry website on the Internet and jotted down the address. We booted up her horrible old computer, a thing with no R nor P nor apostrophe on it, and launched ourselves into the World Wide Web. There was the webpage and they had every sort of chicken and fowl you could dream of. There were photos of them and descriptions of their qualities and advantages, and, lo and behold, in some cases, they even had them starring in their own videos. We could audition our chickens online.

First of all we decided to check out the Andalusian Blue. It was represented in a five-minute video clip. We clicked the

right arrow and waited with excitement for the film to upload. Ah yes, there it was, a real stonker of a chicken. It was

standing

on some beaten earth near a cornfield. We watched as it stared in a desultory manner at the camera and then turned its head to look to the left for a while. Then, getting bored with that, it looked to the right. There was an atmospheric soundtrack that consisted of some water dripping and

crickets

doing their stuff. After a while the chicken decided to look straight ahead again, giving us an excellent view of its beak.

I looked at Ana, then back at the screen. The chicken was still looking straight ahead. Ana then looked at me. I was looking at the screen. I was still enjoying the video, although I had to admit that it was a bit short on action. You sort of felt that something was going to come along and grab the chicken, a scenario with which we were only too horribly familiar, but one which you couldn’t help feel would add something to the plot. Nothing came along to grab the chicken, though. It shifted its weight and looked down at the ground, a bit bashfully, I thought.

‘Christ, it’s like watching an Ingmar Bergman film,’ I said.

‘Ssh,’ Ana admonished. ‘I think something’s happening.’

The chicken looked up again and twitched. There were a few wisps of dried grass on the ground. I believe the chicken was thinking about pecking them. Occasionally they shifted a little as some infinitesimal zephyr passed. The chicken looked down at them again. I looked at Ana again. I like Ana; I’ve lived with her for a long time. It was a hot evening and she was wearing one of those strappy little tops. I was starting to get bored with the film and just a little amorous. I slipped my arm round her shoulders. She turned and frowned at me.

‘Look,’ she said. ‘We’re supposed to be choosing chickens. What do you think of the Andalusian Blue?’

‘It’s OK,’ I said, noncommittally.

And so on to the Lords. These were the ones with bald necks like vultures, hideous to look at but a beast in the

egg-laying

department. We reckoned them marginally more

interesting

on screen than the Andalusian Blues; they seemed to have more charisma. At long last the credits began to roll on the Lords, too. Five minutes can be a long time. But whatever the longueurs of the videos, any chicken fancier worth their salt had to admit that the selection was truly impressive. Things had come a long way since a poultry van from Ciudad Real would come to Órgiva every Friday, stacked to the gunwales with partridges, quails, guinea fowl and chickens.

We chose a couple of the Andalusian Blues, a couple of Lords, a couple of Prats (don’t ask me why), and a grey cock. After we pressed the appropriate keys, delivery would be by courier within twenty-four hours. We set about putting the final touches to the chicken run.

Amazingly, the very next afternoon the chickens arrived in town. They came packed in two custom-made cardboard boxes in a little van. I drove them home and Ana and I gathered in the chicken run, having made a very heaven of it, to release them. As always with poultry, they lurked in the corner looking unutterably depressed. Ana suffers deep anguish about this, but I am more sanguine, and do not attribute to the humble hen either the limitless subtlety or the broad range of emotions that we higher beings enjoy. Poultry are either depressed or alright; there are no middling shades of grey. And I imagine that the experience of being grabbed and stuffed into a cardboard box and then shipped for four hours would tend towards the depressing rather than the uplifting. Until something positive occurred to convince them otherwise, they would remain depressed.

So we went down to the farm in search of the sort of

positive

thing that we thought would make a chicken feel alright. It would have to be food because, along with sex, food is the only thing chickens are interested in, and these were too young to care much about sex, which was perhaps just as well, because the sort of sex that chickens have looks pretty ghastly, particularly for the poor hen.

So we got them some

Robinia pseudoacacia

leaves, alfalfa, dandelions, vervain and chickweed. Fortunately the

vegetable

garden is always rich in greenery, and Ana knows exactly what chickens love and what they don’t like at all. Funny that they should love the

Robinia

, the black locust tree, because in order to check the spelling I looked it up on the Web, only to find that the leaves contain robin, a toxin that gives horses anorexia, depression, incontinence, colic, weakness and cardiac arrhythmia. It’s probably a question of dose.

We lovingly arranged bunches of all these plants around the place, but the young chickens only looked at them with deepest suspicion … and now I know about the

Robinia

I’m not surprised. We tried them with oranges, apricots, plums and loquats, all the most delicious fruits in season, but even this failed to raise their enthusiasm.

By now we had reinstated our old ‘chicken bucket’ to its pride of place on the kitchen counter and once more began to throw in all the leftovers that we believe chickens like: lettuce and carrots, cucumbers and parsley. These have to be chopped up into peck-sized pieces. Potato peelings have to be boiled a bit, but then they like them, along with rice and pasta. The detritus of prawns is popular with most chickens, too … but what really gets them going is, I’m afraid to say, chicken. It is by a long head their favourite thing. Urban friends and visitors are appalled to see us giving chicken

scraps to the chickens, but only because they don’t know the score, the way things are in the country.

Chicken and prawns are not something we eat that often, so the air of depression continued for some weeks, with the whole lot of them huddled miserably in a corner of the chicken run, until Ana went in to feed and water them, whereupon they would scatter in a terrified squawking panic. There was no sign of any eggs; they were too young for that. Soon the depression started to get to Ana.

‘I wonder about these chickens,’ she said. ‘They’re no fun at all and they don’t lay any eggs.’

‘Be patient, dear,’ I suggested. ‘All in its own sweet time.’

As the weeks went by the chickens began to get big and beautiful; the lavish feeding routine was paying off. And then one day Ana returned ecstatically from the chicken run holding the first egg. After that the eggs came in veritable cascades; we were getting five a day and often a big

double-yolker

, for which, according to the chicken website, the Prats were famous. A sense of gladness pervaded our lives as the larder began to fill.

Before long we had reached that interesting state where production was beginning to exceed demand. It occurred to us that, just as we had needed the chickens to relieve us from the burden and waste of left-over food, we now needed Chloé back to relieve us from the glut. Neighbours were no help as they all had chickens themselves, and, although we could have fed the eggs to the dogs, it seemed excessive and a waste, because dogs don’t appreciate the qualities of a good egg. The occasional egg-and-home-produce run to Chloé’s Granada lodgings seemed like the best solution, and a fine, unobtrusive way to keep in touch.