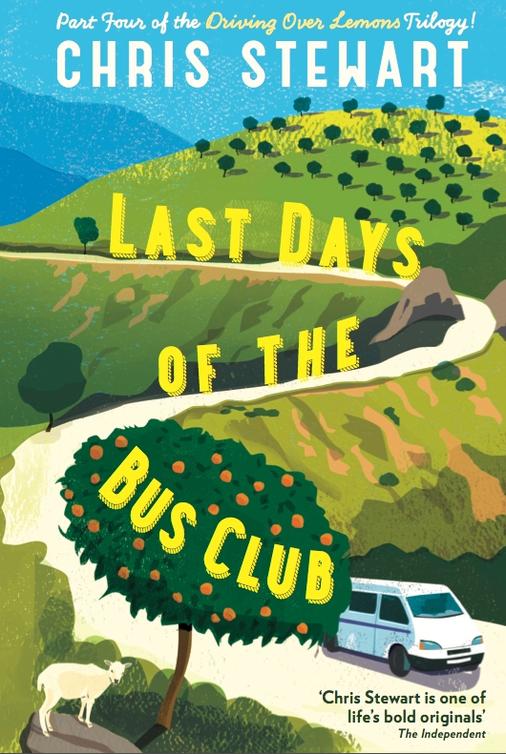

Last Days of the Bus Club

Read Last Days of the Bus Club Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

Comments on

THE DRIVING OVER LEMONS TRILOGY

A wonderful book – funny, affectionate and reaching deep beneath the skin. Tuck it into your holiday luggage and dream.

Elisabeth Luard,

Daily Mail

Exquisite: the anecdote flourishes once more.

Penelope Lively,

Daily Telegraph

A funny, observant and personal account of what a man can learn, and what there is to appreciate in life. Marvellous.

John S. Doyle,

The Sunday Tribune

Everything that made the first book so successful – endearing, heart warming, self-deprecating, sometimes surreal… charming stuff.

William Leith,

The Standard

You just can’t fail to like him and the world he spreads out for you: wayward sheep, eccentric ex-pats, hospitable (and slightly barmy) neighbours. Stewart is that rare thing, the real McCoy.

Rosie Boycott,

The Guardian

DRIVING OVER LEMONS

A PARROT IN THE PEPPER TREE

THE ALMOND BLOSSOM APPRECIATION SOCIETY

The fourth book in the Driving Over Lemons trilogy

Chris Stewart

For Michael Jacobs

my favourite travelling companion

- Title Page

- Dedication

- 1.

Last Days of the Bus Club - 2.

Rick Stein and the Wild Boars - 3.

The Green, Green Rooves of Home - 4.

How El Valero Got Its Name - 5.

Deer Leap - 6.

A 4B Pencil - 7.

Virtual Chickens - 8.

Breakfast in Medina Sidonia - 9.

Cures for Serpents - 10.

Manualidades - 11.

The Rain in Spain - 12.

Crimes and Punishments - 13.

An Author Tour (with Sheep) - 14.

How Not to Start a Tractor - 15.

Santa Ana - 16.

Oranges and Lemons - 17.

All the Fun of the Feria - About the Author

- Also by Chris Stewart

- Copyright

T

HROUGH ALL THE YEARS

of my daughter Chloé’s schooling it fell to me to get the family ship under way in the morning. I function better in the early hours; Ana, my wife, lasts longer into the night than I do. And so it was that on a cool September morning, the first day of Chloé’s last year at school, I rose in the dark. At six forty-five it’s still dark where we live, in the mountains of Granada, as, even at summer’s end, the sun takes its time rising above the cliffs behind our home. Leaving my wife and the dogs fast asleep in the bedroom, I padded across the cold stone floor to the bathroom, splashed my eyes with cold water, dressed, and went into the kitchen. I put the kettle on, lit the candles for the breakfast table and at seven o’clock I woke Chloé. In all the fourteen years of the school run I did not have to wake her again more than on one or two occasions. She loved school, and would appear without fail ten minutes

later blinking in the candlelight and clutching her heavily stacked backpack.

Chloé’s breakfast, a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice and a bowl of some absurd industrially modified cereal product – Choco Kreks, ideally – was already on the table, while I busied myself with the first task of the day: the preparation of her mid-morning sandwich. In the creation of these little masterpieces I employed all the imagination and artistry I possess. I couldn’t bring myself to inflict upon my daughter the standard Spanish

bocadillo

– a dry and artless roll, unaccountably afforded the status of cultural icon in spite of its curious quality of emerging from the oven almost completely stale. No, for Chloé’s delectation I would first select a better class of bun – and these are to be had, if you know where to look. (Supermercado Mercadona, top left corner of the bakery section, labelled ‘Mini Ciabattas’.)

These I would slit open with a razor-sharp knife, leaving an infinitesimal hinge of crust. Then I would oil them up a bit with a little extra-double-virgin, cold-pressed, unfiltered, single-variety, single-estate olive oil from our own Picual trees, add a layer of thinly sliced tomatoes (ready salted to enhance the flavour), a dab of sugar to counteract the acidity, a couple of transparently thin slivers of fresh garlic, some Genoese basil, and finally a dollop of mayonnaise to help the whole concoction slip down … oh, and a few chives sticking out of the end like whiskers on a prawn.

This was the vegetarian option. There was a meat one, too, with exquisite

embutidos

– the preserved meats that the Spanish do rather well – enlivened by a scattering of sliced gherkins, some chilli sauce perhaps, and a handful of herbs.

Or the oriental

bocadillo

with ginger, chutney, a prawn or two and some beansprouts.

I would then slip a couple of these into one of those silver bags that vacuum-packed coffee comes in; they fit perfectly and it made them smell of fresh coffee, which Chloé, especially when little, didn’t like, but I thought would set her up for the future.

In truth these snacks were not always greatly to Chloé’s taste. When young, she disliked being marked out as different from her peers, and would mournfully report that she had shared her

bocadillos

with her friends, and the friends, who were no doubt busy trying to get their teeth through their own stale dry buns, had not thought much of them. But gradually things changed, and Chloé, charged with the nostalgia teenagers develop for their infancy, increasingly accepted my creations for what they were – simple manifestations of love.

That morning, with an atmosphere of newness that comes with the first day back at school, the

bocadillos

crammed in amongst the books in Chloé’s backpack, and the backpack on my back, we left the house to walk down the hill and across the valley, with Bumble and Bao, the dogs, sniffing the fresh morning scents behind us.

The first rays of sunshine were already warming the far side of the valley, as we walked past the stable, pausing to catch the cacophony of farting and coughing with which the sheep habitually start the day, and hastened upriver amongst the oleanders and tamarisk to the bridge. Our bridge, being a ramshackle contrivance of worm-eaten

eucalyptus beams thrown across the river, has no railings, and tends to sag and creak if you creep gingerly across it. So we don’t; casting caution to the side we leap down the bank and race across as fast as we can go. For late summer there was a good flow of red-tinged, iron-rich water

rushing

down the river. With only minutes to go now we

scrambled

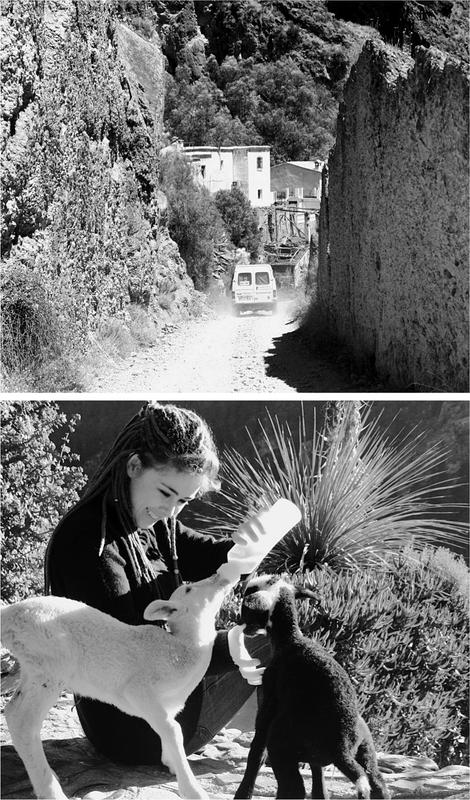

into the aged Land Rover – no doors – and accelerated off along the sandy tracks in the riverbed, and up the hill towards the final stop on the school bus route, just above La Cenicera, the farm where our Dutch neighbour Bernardo lives.

Jesús, who keeps a flock of goats and sheep high up on Carrasco, the hill farm opposite us, was already there in his little white van, and Bernardo was leaning on its roof,

chatting

to him through the open window.

In a cloud of dust we hurtled past the little gathering and raced to get the car turned round before the bus came. The dust had hardly settled before the bus nosed cautiously round the corner. There was a rush and tumble of frantic kissing as Bernardo kissed his son Sebastian, Jesús kissed his boys José and Javier, and I kissed Chloé, and they climbed onto the bus, leaving us three fathers waving until it disappeared round the corner.

And so began the morning’s meeting of the three fathers of the valley – Bernardo, Jesús and me – or the Bus Club, as I liked to call it. I think we all rather cherished being able once again to have these few minutes together at the start of a weekday; we had missed it over the long summer months. It gave us a chance to discuss what was going on

in the valley, exchange what scant news there was from the town, and reminisce a little.

Inspired perhaps by the presence of a horrible-looking cur of a dog that was sniffing the wheel of Jesús’s van, perhaps with a view to urinating in a small way against it, Bernardo was telling a scurrilous tale that featured dogs. We learned that he had a bitch on heat, and he had locked her in the bathroom in order to protect her from the

lascivious

attentions of the hordes of male curs who had travelled from the four corners of the province of Granada to press their suits.

‘I locked ’er in de barfroom,’ he said, ‘because it’s de only place wid a lock on de deur, an’ dere wass orl dese doggs howlin’ an’ barkin’ an’ slobberin’ about der place orl nite long an’ I don’t want ’em to get at ’er.’

‘Very sensible,’ Jesús and I concurred.

‘Only when I come out in de mornin’ de whole lot of ’em was down in de barfroom wid der bitch, dey gone an’ dug a ’ole through de roof.’

‘Ah,’ I observed sagely. ‘You can’t lock the door on love, Bernardo.’ Jesús grinned in agreement.

‘Dat’s not lurv,’ exclaimed Bernardo, looking at us in amazement, ‘Dat’s jus’ doggs fockin’.’

Of course we spoke in Spanish, because Jesús was limited to his native tongue, but I have written this little exchange in a sort of cod Dutch-English, in an attempt to give the flavour of Bernardo’s Spanish, which is extremely good, but at least as idiosyncratic as my own.

Turning to Jesús, I asked after Ana and María-José, his two daughters. Not so long ago they too had waited for this same bus, like two baby birds they seemed, with backpacks on. But a couple of years ago they’d left to go to university

in Granada. It’s always a pleasure to ask Jesús about his daughters just to see the honest pride it stirs in him. When they were schoolgirls, Jesús would answer with a fond, if slightly mystified, expression, ‘Oh, they’re doing fine.’ He wasn’t even really sure what they were studying; it was so far removed from the experience of this hard-working man who had lived and raised his family by the strength of his arm and the milk of his goats. But the day that Ana and Maria-José took their seats in the lecture halls of Granada University – one to study Business Administration, the other Economics – was a giant step for their family and the valley, and it was felt by all of us. A generation earlier it would have been almost impossible for country girls like these to attend university; they would have been needed to help on the farm, and a farm’s meagre returns would certainly not have stretched to tuition fees and

accommodation

in the city.

‘Ay, Cristóbal,’ he said. ‘Enjoy this year with Chloé while you can; it’ll be gone in a flash and she’ll be off.’

Bernardo nodded knowingly; his two eldest were also living in Granada, while Rosa his younger daughter, who used to be Chloé’s playmate, was about to leave to work for an NGO in Colombia. It seemed that the children of the valley were disappearing fast. Though Jesús still had the two boys, and Bernardo his Sebastian, my days in the Bus Club were numbered. I changed the subject a little abruptly.

‘I’ve got a lamb for you, Jesús, if you want it,’ I said.

‘Seems an odd time to be lambing.’

‘I know, but we have a few out-of-season lambers, covered by a rogue ram. Anyway, one of them has twins and I don’t think she’s got enough milk for both of them. Have you got goats milking at the moment?’

‘There’s always goats to milk,’ said Jesús with

resignation

. ‘I’ll be happy to take it.’

‘Then I’ll bring it to Bus Club tomorrow.’

And so saying, we all set off home to our respective breakfasts.

It was not many weeks after the beginning of the term that I got a call from Chloé’s school. It was from the assistant head, no less, and she wondered if, as a local author

accustomed

to regaling the public on the subject of my books, I might like to give a talk to the Instituto classes?

‘Of course,’ I said. ‘What do you want me to talk about?’

‘Oh, whatever takes your fancy, really. We’ll leave the subject up to you.’

Well, addressing the school would be

pan comido

, I thought (the Spanish say ‘bread eaten’ rather than ‘a piece of cake’). You don’t have to prepare a thing like this; you just turn up and do it.

Or perhaps not. For, when I told Chloé, she expressed some concern.

‘You’ve got to prepare this speech, Dad,’ she insisted. ‘The Instituto class is only a year below me. They’re my friends, or at any rate the younger brothers and sisters of my friends.’

This gave me pause for thought, for apart from not wishing to shame my daughter I was a great admirer of Órgiva’s school and its staff. It had done what Ana and I considered an excellent job, despite the fact that when we enrolled Chloé, Spain had one of the worst education records in Western Europe, and Andalucía the worst in Spain. But

due to some fortunate glitch round about the turn of the new century – a good headmaster and some inspirational teachers – San José de Calasanz was different.

Chloé was emerging from school with an easy sociability, a confidence in her own judgement and a laudable streak of anti-materialism bordering on contempt for fashion brands and accessories. These qualities might have had something to do with our own attitudes, but the ideas were consolidated by her

pandilla

at school. And the

pandilla

, the gang of girls and boys with whom she hung out, taught her to deal easily and naturally with her fellow beings, and to be comfortable in her own skin in a peculiarly Mediterranean way. This counts for a lot, and I was proud of Chloé and deeply grateful to all those who had helped to bring her up.