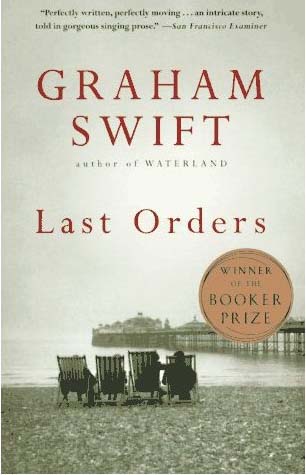

Last Orders

Annotation

The Man Booker Prize Winner—1996

The author of the internationally acclaimed Waterland gives us a beautifully crafted and astonishingly moving novel that is at once a vision of a changing England and a testament to the powers of friendship, memory, and fate.

Four men—friends, most of them, for half a lifetime—gather in a London pub. They have taken it upon themselves to carry out the “last orders” of Jack Dodds, master butcher, and carry his ashes to the sea. And as they drive to the coast in the Mercedes that Jack's adopted son Vince has borrowed from his car dealership, their errand becomes an epic journey into their collective and individual pasts.

Braiding these men's voices—and that of Jack's mysteriously absent widow—into a choir of secret sorrow and resentment, passion and regret, Graham Swift creates a work that is at once intricate and honest, tender and profanely funny; in short, Last Orders is a triumph.

- Graham Swift

- Editorial Reviews

- Bermondsey

- Ray

- Bermondsey

- Ray

- Old Kent Road

- Amy

- New Cross

- Vince

- Ray

- Blackheath

- Vince

- Ray

- Lenny

- Dartford

- Ray

- Vince

- Lenny

- Vince

- Gravesend

- Vie

- Ray

- Vince

- Ray

- Vince

- Ray

- Chatham

- Vie

- Ray

- Lenny

- Ray

- Vince

- Lenny

- Chatham

- Vie

- Wick's Farm

- Ray

- Mandy

- Vince

- Ray

- Lenny

- Wick's Farm

- Ray

- Vince

- Ray

- Canterbury

- Lenny

- Vie

- Vince

- Ray

- Ray'S Rules

- Lenny

- Vie

- Ray

- Lenny

- Vie

- Ray

- Canterbury

- Vie

- Amy

- Ray

- Amy

- Vie

- Ray

- Amy

- Ray

- Margate

- Vince

- Amy

- Margate

- Amy

- Ray

- Jack

- Margate

- Editorial Reviews

Last Orders

Editorial Reviews

This is Graham Swift's finest work to date: beautifully written, gentle, funny, truthful, touching and profound.Salman Rushdie

BermondseyA novel of impeccable authenticity …The New York Times Book Review, Jay Parini

It aint like your regular sort of day.

Bernie pulls me a pint and puts it in front of me. He looks at me, puzzled, with his loose, doggy face but he can tell I don't want no chit-chat. That's why I'm here, five minutes after opening, for a little silent pow-wow with a pint glass. He can see the black tie, though it's four days since the funeral. I hand him a fiver and he takes it to the till and brings back my change. He puts the coins, extra gently, eyeing me, on the bar beside my pint.

'Won't be the same, will it?' he says, shaking his head and looking a little way along the bar, like at unoccupied space. 'Won't be the same.'

I say, 'You aint seen the last of him yet.'

He says, 'You what?'

I sip the froth off my beer. 'I said you aint seen the last of him yet.'

He frowns, scratching his cheek, looking at me. 'Course, Ray,' he says and moves off down the bar.

I never meant to make no joke of it.

I suck an inch off my pint and light up a snout. There's maybe three or four other early-birds apart from me, and the place don't look its best. Ghilly, a whiff of disinfectant, too much empty space. There's a shaft of sunlight coming through the window, full of specks. Makes you think of a church.

I sit there, watching the old clock, up behind the bar. Thos. Slattery, Clockmaker, Southwark. The bottles racked up like organ pipes.

Lenny's next to arrive. He's not wearing a black tie, he's not wearing a tie at all. He takes a quick shufty at what I'm wearing and we both feel we gauged it wrong.

'Let me, Lenny,' I say. 'Pint?'

He says, 'This is a turn-up.'

Bernie comes over. He says, 'New timetable, is it?'

'Morning,' Lenny says.

'Pint for Lenny,' I say.

'Retired now, have we, Lenny?' Bernie says.

'Past the age for it, aint I, Bern? I aint like Raysy here, man of leisure. Fruit and veg trade needs me.

'But not today, eh?' Bernie says.

Bernie draws the pint and moves off to the till.

'You haven't told him?' Lenny says, looking at Bernie.

'No,' I say, looking at my beer, then at Lenny.

Lenny lifts his eyebrows. His face looks raw and flushed. It always does, like it's going to come out in a bruise. He tugs at his collar where his tie isn't.

'It's a turn-up,' he says. 'And Amy aint coming? I mean, she aint changed her mind?'

'No,' I say. 'Down to us, I reckon. The inner circle.'

'Her own husband,' he says.

He takes hold of his pint but he's slow to start drinking, as if there's different rules today even for drinking a pint of beer.

'We going to Ws?' he says.

'No, Vic's coming here,' I say.

He nods, lifts his glass, then checks it, sudden, half-way to his mouth. His eyebrows go even higher.

I say, 'Vic's coming here. With Jack. Drink up, Lenny,'

Vie arrives about five minutes later. He's wearing a black tie but you'd expect that, seeing as he's an undertaker, seeing as he's just come from his premises. But he's not wearing his full rig. He's wearing a fawn raincoat, with a flat cap poking out of one of the pockets, as if he's aimed to pitch it right: he's just one of us, it aint official business, it's different.

'Morning,' he says.

I've been wondering what he'll have with him. So's Lenny, I dare say. Like I've had this picture of Vie opening the pub door and marching in, all solemn, with a little oak casket with brass fittings. But all he's carrying, under one arm, is a plain brown cardboard box, about a foot high and six inches square. He looks like a man who's been down the shops and bought a set of bathroom tiles.

He parks himself on the stool next to Lenny, putting the box on the bar, unbuttoning his raincoat.

'Fresh out,' he says.

'Is that it then?' Lenny says, looking. 'Is that him?'

'Yes,' Vie says. 'What are we drinking?'

'What's inside?' Lenny says.

'What do you think?' Vie says.

He twists the box round so we can see there's a white card sellotaped to one side. There's a date and a number and a name: JACK ARTHUR DODDS.

Lenny says, 'I mean, he aint just in a box, is he?'

By way of answering Vie picks up the box and flips open the flaps at the top with his thumb. 'Mine's a whisky,' he says, 'I think it's a whisky day.'

He feels inside the box and slowly pulls out a plastic container. It looks like a large instant-coffee jar, it's got the same kind of screw-on cap. But it's not glass, it's a bronzy-coloured, faintly shiny plastic. There's another label on the cap.

'Here,' Vie says and hands the jar to Lenny.

Lenny takes it, uncertain, as if he's not ready to take it but he can't not take it, as if he ought to have washed his hands first. He don't seem prepared for the weight. He sits on his bar-stool, holding it, not knowing what to say, but I reckon he's thinking the same things I'm thinking. Whether it's all Jack in there or Jack mixed up with bits of others, the ones who were done before and the ones who were done after. So Lenny could be holding some of Jack and some of some other feller's wife, for example. And if it is Jack, whether it's really all of him or only what they could fit in the jar, him being a big bloke.

He says, 'Don't seem possible, does it?' Then he hands me the jar, all sort of getting-in-the-mood, like it's a party game. Guess the weight.

'Heavy,' I say.

'Packed solid,' Vie says.

I reckon I wouldn't fill it, being on the small side. I suppose it wouldn't do to unscrew the cap.

I pass it back to Lenny Lenny passes it back to Vie.

Vie says, 'Where's Bern got to?'

Vic's a square-set, ready-and-steady sort of a bloke, the sort of bloke who rubs his hands together at the start of something. His hands are always clean. He looks at me holding the jar like he's just given me a present. It's a comfort to know your undertaker's your mate. It must have been a comfort to Jack. It's a comfort to know your own mate will lay you out and box you up and do the necessary So Vie better last out.

It must have been a comfort to Jack that there was his shop, Dodds & Son, Family Butcher, and there was Vic's just across the street, with the wax flowers and the marble slabs and the angel with its head bowed in the window: Tucker & Sons, Funeral Services, A comfort and an. incentive, and a sort of fittingness too, seeing as there was dead animals in the one and stiffs in the other.

Maybe that's why Jack never wanted to budge.

RayFd said to Jack, 'It aint never gone nowhere,' and Jack'd said, 'What's that, Raysy? Can't hear you/ He was leaning over towards Vince.

It was coming up to last orders.

I said, 'They calls it the Coach and Horses but it aint never gone nowhere.'

He said, 'What?'

We were perched by the bar, usual spot. Me, Lenny, Jack and Vince. It was young Vince's birthday, so we were all well oiled, Vince's fortieth. And it was the Coach's hundredth, if you could go by the clock. I was staring at it - COACH AND HORSES in brass letters round the top. Slattery. 1884. First time I'd thought of it. And Vince was staring at Bernie Skinner's new barmaid, Brenda, or was it Glenda? Or rather at the skirt she was squeezed into, like she was sitting down when she was standing up.

I wasn't just staring at the clock, either.

Jack said, 'Vince, your eyes'll pop out.'

Vince said, 'So will her arse.'

Jack laughed. You could see how we were all wishing we were Vincey's age again.

I hadn't seen Jack so chummy with Vince for a long time. Maybe he was having to be, on account of it being Vincey's big day. That's if it was his big day, because Lenny says to me, same evening, when we meet up in the pisser, 'Have you ever wondered how he knows it's his birthday? Jack and Amy weren't ever a witness, were they? They never got no certificate. My Joan thinks Amy just picked March the third out the air. April the first mightVe been a better bet, mightn't it?'

Lenny's a stirrer.

We stood there piddling and swaying and I said, 'No, I aint ever wondered that. All these years.'

Lenny said, 'Still, I forget my own birthday these days. It's been a while since the rest of us saw forty, aint it, Ray?'

I said, 'Fair while.'

Lenny said, 'Mustn't begrudge the tosser his turn.' He zipped up and lurched back into the bar and I stood there staring at the porcelain.

I said, 'Daft name to call a pub.' Jack said, 'What's that?'

I said, 'The Coach. The Coach. I'm trying to tell you.' Vince said, looking at Brenda, 'It's Ray's joke.' 'When it aint ever moved.'

Jack said, 'Well, you should put that right, Raysy. You're the one for the horses. You ought to tell old Bernie there to crack his whip,'

Vince said, 'She can crack my whip any day.' Jack said, Til crack your head. If Mandy don't.' And he only said it in the nick of time because half a minute later Mandy herself walks in, come to fetch Vincey home. She's been round at Jack's place, nattering with Amy and Joan. Vincey don't see her, looking at other things, but Jack and me do but we don't let on, and she comes up behind Vince and spreads her hands over his face and says, 'Hello, big eyes, guess who?'

She aint built on Brenda's lines any more but she's not doing so bad for nearly forty herself, and there's the clobber, red leather jacket over a black lace top, for a start. She says, 'Come to get you, birthday boy' and Vincey pulls down one of her hands and pretends to bite it. He's wearing one of his fancy ties, blue and yellow zig-zags, knot pulled loose. He nibbles Mandy's hand and she takes her other hand from his face and pretends to daw his chest. So when they get up to go and we watch them move to the door, Lenny says, 'Young love, eh?', his tongue in the corner of his mouth.

Other books

Magic Nation Thing by Zilpha Keatley Snyder

Blasfemia by Douglas Preston

The Decimation of Mae (The Blue Butterfly) by Sidebottom, D H

The Forest Lord by Krinard, Susan

Wickedly Ever After: A Baba Yaga Novella by Deborah Blake

Vespers by Jeff Rovin

A Darker Shade of Sweden by John-Henri Holmberg

The Cat Who Walks Through Walls by Robert A Heinlein

Designed for Love by Roseanne Dowell

The Muffin Tin Cookbook by Brette Sember