Read Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents Online

Authors: Minal Hajratwala

Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents (49 page)

Raju (Roger), the entrepreneur, at his wedding in Toronto, showing a gift, ca. 1987.

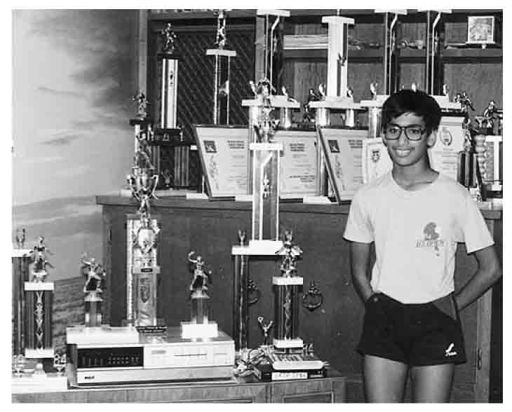

Dhiren, the table tennis player, with his trophies, early '80s.

Praveena with her students in the new, postapartheid South Africa, 2002.

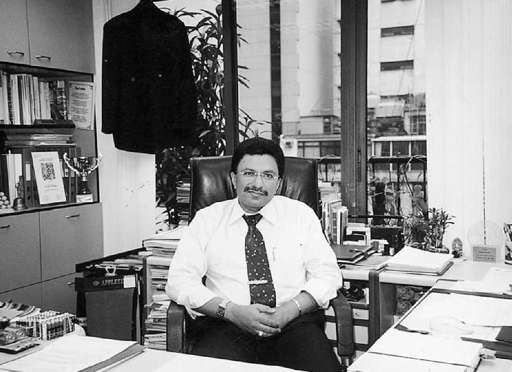

Hemesh, the Hong Kong import-export businessman, in 2001.

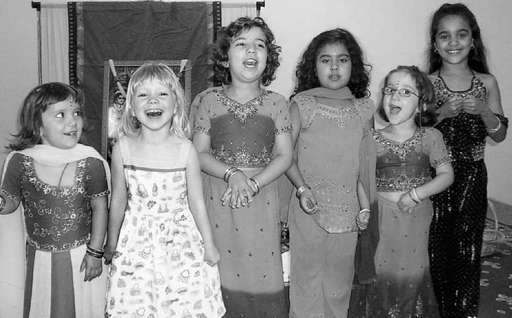

The next generation: my nieces with their cousins, 2007. Left to right: Ava Naasko Hajratwala, cousin Ella, Zoë Naasko Hajratwala, cousin Sonia, Téa Naasko Hajratwala, cousin Trina. They all live in suburban Michigan.

To assimilate means to give up not only your history but your body, to try to adopt an alien appearance because your own is not good enough, to fear naming yourself lest name be twisted into label...

—Adrienne Rich

D

EEP IN THE MARROW

of every story is a silence. Having struggled, all these pages, to be transparent, not to overwhelm the stories of others with my own, now it is my turn to emerge, solid. And I hardly know where to begin. I have practiced the art of submergence—invisibility, assimilation—all my life. To metamorphose, now, from neutral narrator to embodied character, self, seems a great act of exposure. Vulnerability, guilt, freedom, sympathy: Which thread shall I pull first? How shall I unravel or construct, from all of my memories and aches, one true pattern, one set of possibilities—one spine?

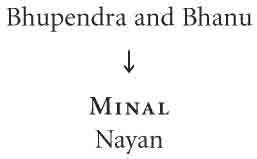

I might have been named Gita, Saroj, or Sudha. I might have had trouble in school, been raised under the shadow of Mars, and brought good luck to my house. The telegram my father sent from San Francisco to Fiji at my birth was un-mystical:

BABY GIRL BORN 742 PM MONDAY JULY 12TH STOP BHANU AND MINAL IN GOOD HEALTH LETTER FOLLOWS BHUPENDRA

It was 1971. My grandmother in Fiji forwarded the vital information—date, time, time zone—to her astrologer in India. He wrote my horoscope, which predicted all of the above. Based on an ancient calculus, the stars said my name should start with

G

or

S.

My grandmother sent a gift for "Gita."

But I had already been named, as my parents reminded her:

meen

meaning "fish,"

al

meaning "like."

Minal,

she who is like a fish. They were college-educated, beyond superstition; they had named me for a friend of my mother's, just because they liked the sound of the name. They declined to read the trajectory of my life ahead of time: lucky and unlucky years, characteristics of a compatible mate, probable paths of education, marriage, and health. Nor did they perform the sixth-night ceremony, when a pencil and paper are placed under the baby's crib, for the goddess of destiny to write.

And so I was raised free of predestination.

But not entirely.

My parents believed in destiny, even as they doubted the importance of ritual in shaping it; and the telegram my father received that day—the job offer from the south of the planet—was a kind of proof. With or without a written horoscope, I entered the world with a lucky footprint.

Within six months I was an emigrant, collecting the first international stamp on my passport. I slept all the way from San Francisco to New Zealand in an airline bassinet, aided by a lick of whiskey.

In the normal manner, I progressed from howling to cooing to, eventually, words. In New Zealand I believed we had our own special language, a delightful singsong made up by my parents. It was a code we could use in the public park, where we fed our stale bread-ends from the week to the ducks, or in the grocery store to discuss the funny-looking woman nearby, say, or complain about prices that were too high. No one could decipher our secrets. We used it just for fun, too: My mother said it was time to

inter-pinter

the laundry, to move it from washer to dryer. A bumpy road was so

gaaber-goober,

she complained. She could double any word or name to humorous effect, or for emphasis: Minal Binal, TV BV, bowling phowling.

It was only when we visited India, when I was four years old, that I understood there was a world of other people who spoke the same funny way. Gujarati was a lilting, rhyming language, and with a child's knack I absorbed it completely in the six weeks of our visit. By the time we left India, I had forgotten all of my English.

***

I never thought of myself as an immigrant until I began writing this book. Because I was born in San Francisco and now live in San Francisco, my mind skipped over the years of disruption in between; I believed I was only the child of immigrants, the so-called second generation. But the truth is, I have lived through multiple migrations, shifts from one world to another; and these geographic shifts were mirrored and amplified into emotional, mental, and even sexual ones. Each time I cross a border, I feel the push and pull in my body, a cacophony of competing desires. And always there are choices to make: what to assimilate, what to reject. Is it true that we are always, as migrants, and the children of migrants, attempting to choose what my parents call "the best of both worlds"? Or is it possible to transcend—no, not transcend, but enter into—the dualism, the splitting, the uncertain interstices between the worlds? Is it possible to integrate, even heal, the trauma of crossing; of many crossings?

Back home in New Zealand, my Kiwi babysitter was forced to learn a few basic words in Gujarati for a few weeks, until my tongue acclimated again.

Water, hungry, yes, no.

Eventually I would become adept, like all children raised with more than one language, at code-switching, knowing instinctively when to use Gujarati and when to use English. Meanwhile Mrs. Maclean acquired

pani, bhukh, haa, naa.

She fed me Jell-O and a soft-boiled egg for lunch every weekday while my parents were at work. She was our next-door neighbor, and my mother also traded recipes with her—rotli for trifles, curries for brandy snaps. Her daughters, Philippa and Vicki, became my best friends. We were partners in spitting watermelon seeds, hunting for golf balls on the nearby course, and taking swim lessons at the Y. We watched television, and I developed a secret crush on Adam West as Batman. I called their grandmother Gram, and had no memory of my own.

Five years old, I walked unchaperoned—the streets were that safe—every day to and from Maori Hill Elementary School, which, despite being named for the indigenous people of New Zealand, was populated by a couple of hundred white children, one Maori boy, and me. My teachers had innocent, storybook names: Mrs. Lion, Mrs. Stringer, Miss Babe. Once I lost a 24-karat gold earring on the way to school; a neighbor's son found and returned it. And when one of my kindergarten classmates asked his mother,

Why don't Minal's hands ever get clean?

and she reported this to my mother, they simply laughed: Kids say the darnedest things.

I remember our years in New Zealand as happy ones. Traveling back, I have felt a nostalgia for its green hills and cool southern fog, an unaccountable joy, even a sense of home—the original landscape that my body remembers. But when I was six years old, I began peeling the skin from my lips, obsessively, till they bled. My parents tried everything: scolding, spanking, a trip to the pediatrician. I remember the bitter taste of iodine on my fingers, the night mittens; but none of it worked.

I believe that as children we know things, in an almost prescient way, as animals understand earthquakes; that we absorb mysterious signals, the unspoken anxieties of adults, and the plans that are being hatched around us. Did I sense that my parents were planning to shift continents again, and that they were (although they did not say so, perhaps not even to themselves) afraid? Did I take this fear, worry, and uncertainty into my own small body? When I was seven years old, the world changed.

My parents had decided to move back to the United States. When they broke the news, they tried to sweeten the deal: in America they would buy me one new doll every month, for a whole year. Like legions before me, I was seduced by the New World's promise of wealth beyond imagination.

After touching down in Los Angeles, we toured Disneyland and I picked up a Mickey Mouse cap with ears and my name embroidered in yellow script. This rite of passage was followed by a series of moves whose reasons I understood, vaguely, as being connected to my father's work. Of Gainesville, Florida, I remember the terror of roaches, which I had never seen before. In Iowa City, where we lived for a year, our lives seemed brushed by a glamour that only America could offer. One of my classmates was the son of a minor television star. My best friends were redheaded twins whose father had spent time in India and given them Indian names; when I went to their house for a sleepover, I saw with amazement that they each read a book at the dinner table. The twins borrowed my Indian outfits, and my mother choreographed a Gujarati folk dance at our school's winter show. Christmas was, for the first time, storybook white, and important. My parents bought a plastic tree and gifts, to help us fit in. I sang Christmas carols in my second-grade classroom, where we stood for the Pledge of Allegiance every morning and had

The Hobbit

read aloud to us every afternoon. I learned to ice-skate, to sled, to transform deep drifts of snow into roly-poly men and hollow angels.