Legio XVII: Battle of the Danube (18 page)

Read Legio XVII: Battle of the Danube Online

Authors: Thomas A. Timmes

Tags: #History, #Ancient Civilizations, #Rome

After seven grueling hours, the men and mules reached the summit. Fortunately, none of the mules had fallen and the Legionaries walking along suffered no ill effects. Everyone was breathing more deeply from the exertion and the higher elevation. After a short rest, the tents were set up and the Legion Standards planted in the ground. From their vantage point, the Legates could just see the lead elements of Legio I Raetorum coming into view.

They asked to be the first Legion up the hill and Manius approved the request. When the troops arrived at the base of the mountain, tents were erected and fires lit. The plan called for one Legion per day to climb the hill, which was good planning based on the Legates experience. The cavalry would be last. There was a real fear that the horses would fall, roll, and injure men in their path.

A dozen hospital wagons accompanied the Legions to the steep mountain and then planned to return to Trento with their patients, if there were any. The presence of the hospital wagons did not go unnoticed by the men.

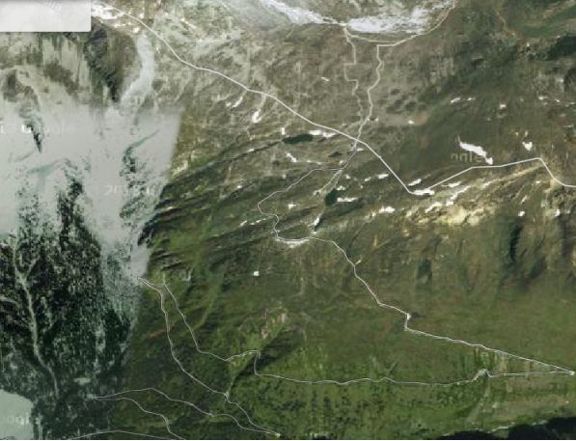

Figure 6: Pathway over the Mountain (Goggle Maps)

*******

At sunrise the next morning, Legio I Raetorum led the way since they were more accustomed to the altitude and could ascend the quickest. They would also set a standard for the others. About half way up, they spotted their Flag and a cheer went up. The following day, Calvus led Legio XVII and tried to out cheer Legio I Raetorum when their own Standard became visible. They were followed the next day by Legio XX. Legio V Etrusci went last and was led by Legate Caile. They made the quickest ascent and cheered the loudest. Legate Caile and his Etruscans are very competitive people.

As each Legion reached the summit, they were directed to a tree covered area about 1,000 yards (914m) away and told where to erect their tents and rest. After Legio V Etrusci was established in their area, Manius and the four Legates met to assess the results of the climb. Essentially, all the Legions performed admirably and the Legates were proud of them, but there were a few incidents.

A Legionary in Legio XVII died on the hill of an apparent heart attack. One mule slipped, fell, and crashed into two other mules which caused two Legionaries significant injuries as they tried to grab them. One had a broken arm; the other a broken wrist. None of the mules suffered any injuries. Seven men felt sick during the ascent and were escorted back down the hill.

At the top, about 100 men were experiencing altitude sickness with headache and nausea. They were immediately walked to the far side of the hilltop and began the descent.

Before the Legates adjourned the meeting, Calvus remarked with a smile that the only reason V Etrusci climbed the hill the fastest is that they were the last to make the ascent and were well rested while sitting and watching the others. Manius noted that Calvus was smiling, but he could see that he meant it. These were, indeed, competitive men! The planners had estimated five days to climb the footpath. Tomorrow would be the fifth day and that was the day for the cavalry to make their ascent.

The Legates walked over to the medical tent to see how the injured were doing. The injured all put on a brave face, but the two with broken bones were in obvious pain. Both of the men said they wanted to continue on to Bad Tolz and not return to the Cantonment at Trento to recuperate.

Manius was disturbed that more and more Legionaries were arriving seeking help with vomiting and headaches. He told the leaders to take the sick men down to the Zillertal Valley (5,346 feet (1629m) where they should begin to recover. He directed the Legates to put the sickest men on mules when they depart, until they felt better and could walk by themselves. Manius returned to his tent. He wasn’t feeling so well either and cancelled the nightly meeting, but not because of his heath, but rather to attend a funeral for the Legionary in Legio XVII that died on the climb.

When the man fell, his tent mates rushed to his aid, but he was already dead. He was a healthy young man one minute and dead the next. It was hard for them to understand. He was well liked by his peers and his sudden, non battle related death, hit them hard. The men put him on a mule that managed to carry the extra weight for a while and then simply stopped. They put the man on another mule and repeated this process until they reached the summit.

The night was cold, but there was no precipitation. Fires were allowed and burned throughout the encampment during the night for warmth and as a tribute to the fallen Legionary. His Maniple built a typical funeral pyre and words were spoken by his Centurion, Tribune, and Legate Calvus. Then the fires were lit. Manius was struck by the number of Legionaries from the other Legions that attended the funeral. The men were bonding, and he was pleased.

By 7:30 A.M. the next day, the summit was crowded with Legionaries. Everyone wanted to watch the horses climb the hill. Many believed they would not be able to do it and anticipated chaos as horses fell and men were crushed and injured by rolling horses and flying hooves. Some actually wanted to witness such a spectacle.

Rasce determined that it would take 12 days for all 900 horses to climb the hill. He figured 75 horses a day would take about 12 hours to get from the bottom of the hill to the top.

By 8:00 A.M. sharp, the first of 75 horses each led by his rider and one volunteer archer entered the trail and began negotiating the winding steep pathway. Rasce’s plan was to space the horse about 20 yards (18m) apart to prevent collisions should one fall. The archer’s job was to support the horse with his arms and back to keep him upright should he begin to lean too heavily to one side.

The horses picked their way carefully; firmly planting each foot before moving the next forward. They showed no reluctance to continue, but did not want to be rushed. The men leading them let them take all the time they needed with just a gentle tug on the rope now and then. About every half mile of trail, the men stopped to let the horses rest and take a drink. So far, the horses were doing better than expected. The fear was that if a horse fell and started to roll, there would be no way to stop it. Rasce told his cavalrymen to simply get out of the way and let it happen. Horses can be replaced.

The archers acting as supports for the horses proved to be critical. They leaned into the horse with their back when a horse lost his footing and held him in position until he could stabilize himself. It was slow going and exhausting for man and beast. Eventually, the Legionary spectators at the summit drifted back to their tents. The horses were not falling and there was nothing to watch.

After 10 hours, the first horse crested the hill. The remaining men still watching gave horse and rider a resounding cheer of approval. Manius had an area designated for the cavalry along with prepared food and feed for the tired climbers.

By 8:00 A.M. the following morning, Legio I Raetorum was on the move northward, followed by Legiones XVII, XX, and V Etrusci. It immediately felt warmer as they descended towards the valley floor, but the Legionaries quickly discovered a new irritant, which grew worse with each step. Their toes were pushed hard into the front of their sandals with each downward step. Men began stuffing grass or whatever they could find into the toe of their sandals, which helped, but walking was still painful. They also noticed that their thigh muscles began to quiver with each step as they braked to slow down. Soon some were forced to alternate walking sideways, even backwards, to keep their legs from shaking so much.

Mercifully, the ground began to level out after a few hours and the Legionaries could walk normally. Most men swore that it was harder going downhill than uphill.

The valley was beautiful this time of year and the walking was easy compared to the monster they had just crossed. The pace picked up to 14 miles (22.5km) a day and they were soon camped in the woods at Jenbach just short of the bridge over the Inn River. Suevi scouts, including Davenhardt, were waiting for them.

The Legions moved into forested areas pre-selected by Davenhardt. Each Legion was tasked to clear a one square mile area of trees, remove large boulders, and lay the foundation for roads. It was hard work and the Legionaries slept well. As units moved across the bridge and up the valley leading to Bad Tolz, they again were led into pre-selected areas and continued the same hard physical work preparing the land for the refugees.

*******

Davenhardt had bonded with the planners at Rome and was anxious to hear the details of their trip. He joined the Legates for the evening meeting and dinner.

Manius brought him up to date on the status of the Raeti pila and wagons at Trento. Davenhardt informed the group that Suevi metal workers were working hard to build 20,000 pila to Roman specification, but they were still working out the details. He told them that the camp at Bad Tolz was staked out and most of the necessary timber had been cut. Manius complimented the Suevi for respecting their part of the plan and said, “Our next challenge is to cross the bridge at Jenbach without being seen.”

Davenhardt said, “We are prepared to block both ends of the east-west road. If the Legions make the crossing at night, it could be done in complete secrecy.”

Legate Caile added, “If we begin the crossing at 9:30 P.M. we will have to stop by 6:00 A.M. before anyone else is on the road. The legions will have to bunch up tightly and march as many men abreast as possible.”

Davenhardt said, “Six men can easily cross the bridge abreast and then it is a short distance before they would disappear from sight as they walk into the valley leading to Bad Tolz.”

*******

Figure 7: Jenbach at Red Marker (Goggle Maps)

During dinner that night, Manius Tullus, the four Legates and key staff Tribunes discussed the final stage of the deployment to Bad Tolz. “I am pleased with our progress so far,” said Manius. “I think we have accomplished everything we set out to do. Our wagons are secured at Trento; thankfully, we have lost only one Legionary and our sick rate is lower than expected. Tribune,” he asked, “how many sick did we leave with the wagons?”

“About 200,” he answered, “and I expect most of them will join us in the spring with Tribune Andreas when he arrives with the 2,000 replacements and the Maniple from Legio XVII.”

Manius then looked at the Tribune in charge of training and asked, “How is the training schedule for Bad Tolz coming along?”

The Tribune replied, “Sir, I can brief the details to you whenever it is convenient. Weather, of course, will dictate some changes, but the training at Bad Tolz combines physical fitness with individual skills training, unit formations, and multi-Legion maneuvers. The specialty troops have already given me their plans. Essentially, when spring arrives you can expect to command eight fully trained and ready Legions. I still need to develop a schedule for the Suevi Legions, which I will do once we arrive at Bad Tolz and I can assess their current status.”

“We know that the Suevi Army that met us in battle last July was brave and willing to fight. These new recruits, however, are mostly made up of refugee farmers, so their capabilities are still unknown. Hopefully, by now, they have been issued swords and shields. One positive aspect of training new recruits is that they are accepting of whatever techniques they are taught. They will only know what they are taught. If we teach them Roman style fighting such as the triplex acies, Maniples, rotating men, and so forth, that will be their normal and they will accept it. Sir, I will keep you informed once we determine their requirements and competency.”