Legions of Rome (10 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

One pack mule was assigned to every squad of a legion, requiring 650 mules for a full-strength legion. The mules were managed by civilian muleteers. A legion baggage train might involve a hundred carts, pulled by mules or oxen and also managed by non-combatants. These carried heavy supplies, artillery, siege equipment, building materials, ammunition, and officers’ dining plate and camp furniture.

Arrian, in the second century, said that Roman commanders were familiar with five set ways of assigning the baggage train in a marching column, all designed to provide maximum protection. Where the army was advancing toward the enemy, he said, it was necessary for the baggage train to follow the legions. When withdrawing from enemy territory, the baggage train went ahead. On an advance where an enemy attack was feared on one flank, the baggage train was placed on the opposite flank. Where neither flank was considered secure, the baggage train advanced in the midst of the legions. [Arr.,

TH

, 30]

A vast body of camp followers inevitably trailed the legions: merchants, prostitutes, de facto legionary families. There were also the slaves of the officers, who took part in arms training and drills with their masters. Said Tacitus, “of all slaves, the slaves of soldiers are the most unruly.” [Tac.,

H

,

II

, 87] The number of non-combatants with an army frequently equaled it in number; when 40,000 Roman soldiers sacked the Italian city of Cremona in

AD

69, they were joined by an even larger number of non-combatants. [Tac.,

H

,

III

, 33]

VII. ARTILLERY AND SIEGE EQUIPMENT

Each legion of the early empire was equipped with one stone-throwing

ballista

per cohort and one metal dart and spear-firing

scorpio

per century. The single-armed catapult of the

onager

or “wild ass” type—so named because of its massive kick—was

employed from 200

BC

and was still employed in

AD

363, when Ammianus Marcellinus saw it in action. “A round stone is placed in the sling and four young men on each side turn back the bar with which the ropes are connected and bend the pole almost flat. Then finally the master [gunner], standing above, strikes out the pole-bolt” with a hammer. [Amm.,

II

, xxiii, 4–6] This released the tensioned firing pole, which sprang forward and launched the missile.

Catapults had a great effect on the morale of both attackers and defenders. All authorities wrote of the enormous noise made by catapults when they fired, and of the terrifying sound made by catapult balls and spears on their way to the target. The normal operating range of legion artillery was 400 yards (365 meters) or less. Catapult stones were used to batter down fortified defenses and eliminate defenders on walls and in towers. A number of scorpio darts have been found at siege sites in modern times, usually with pyramid-shaped heads and three flights made of wood or leather.

The Roman engineer Vitruvius wrote that the Roman military used the following weights for their rounded ballista balls: 2lbs, 4lbs, 6lbs, 10lbs, 20lbs, 40lbs, 60lbs, 80lbs, 120lbs, 160lbs, 180lbs, 200lbs, 210lbs and a massive 360lbs; a range of 0.9 to 163 kilos. [Vitr.,

OA

,

X

, 3] One of the larger balls was nicknamed the “wagon stone,” perhaps because it took a wagon to carry it. [Arr.,

TH

,

II

] Trajan’s Column shows catapult balls packed in a crate, like apples, in which they were delivered to the firing line from the stone-quarries where they originated. The

cheiroballistra

was an improved ballista; in service by

AD

100, it used a metal frame. Light, sturdy and accurate, it was often mounted on a cart for mobility.

Four legions involved in the

AD

70 Siege of Jerusalem employed more than 200 catapults between them. The 10th Legion built a veritable monster of a ballista for this siege. Josephus records that the balls fired against both Jotapata and Jerusalem weighed around 60lbs (27 kilos) and traveled more than 440 yards (400 meters). To make spotting difficult for the Jewish defenders, Roman artillerymen coated their white ballista stones with black pitch. Incendiaries were also used: stones and arrows dipped in pitch, sulfur and naphtha, and set alight. [Jos.,

JW

, 5, 6, 3]

Earth mounds were built for the artillery, to gain elevation over the heads of the infantry. To determine range, Roman artillerymen tossed lead weights on lengths of string to enemy walls, and measured back. As a result of this practice, Roman artillery achieved remarkable and frightening accuracy. At the

AD

67 Siege of Jotapata, where Josephus commanded, a single spear from a scorpion ran through a row of

men. A ballista stone took the head off a Jewish defender standing near Josephus; the man’s head was found 660 yards (600 meters) away. [Jos.,

JW

, 3, 7, 23]

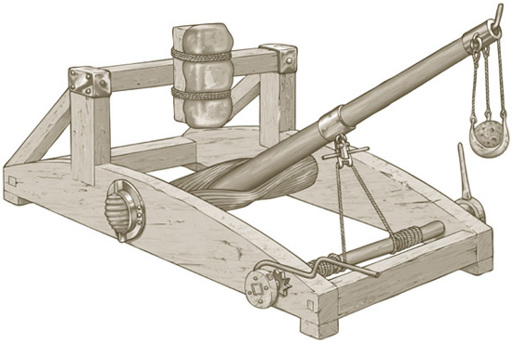

ONAGER CATAPULT

The basic stone-throwing catapult in use for centuries by the Roman military, equipped every legion.

Ammianus described how, in around

AD

363, Roman forces used “fire darts” that had been hollowed out and filled with incendiary material: “oil of general use” mixed with “a certain herb,” which was allowed to stand and thicken “until it gets magic power.” [Amm.,

II

, xxiii, 5, 38] The fourth-century fire-arrow had to be fired slowly, “from a loosened bow,” said Ammianus, “for it is extinguished by swift flight.” But once it landed, it burned persistently. “If one tries to put it out with water he makes it burn the more fiercely, and it can be extinguished in no other way than by throwing dust on it.” [Ibid., 37] As for the “Greek fire” type of incendiary depicted in the feature film

Gladiator

(based on events of

AD

180), this was not developed until the seventh century.

Legionaries were also trained to build wooden siege “engines” for use when fortresses and cities were assaulted. Mantlets, wooden sheds on wheels, were frequently used to provide cover for battering rams. Other war machines, such as a sling used in the defense of Old Camp in

AD

69–70, depended on the ingenuity of individual legions. Siege towers on wheels were common, each with several levels on which artillery was mounted. Elaborate measures to fireproof these towers were not always successful. Siege towers were prominent in the Roman assaults on Jerusalem and Masada in the First Jewish Revolt and in the Siege of Sarmizegethusa during the Second Dacian War.

Caracalla, for his

AD

217 eastern campaign, had two massive siege engines built in Europe which were dismantled and shipped to Syria. Caracalla was assassinated during the campaign, and there is no record of his super siege engines being deployed. By the

AD

359 Persian Siege of Amida, Rome’s enemies had turned her technology against her, employing siege machinery built by Roman prisoners.

By the fourth century, legions were no longer building their own artillery or siege equipment. Nineteen cities in the Roman east and fifteen in the west possessed large government arms workshops by that time, which manufactured catapults and other weapons, armor and siege machinery. Their output was deposited in arsenals in the manufacturing cities and distributed to the military as required. [Gibb.,

XVII

] As a result, legionaries lost the skills that had previously ensured Rome’s legions were, in a great many respects, self-sufficient.

VIII. LEGION, PRAETORIAN GUARD AND AUXILIARY STANDARDS

“The army must become accustomed to receiving commands sharply,” said second-century general Arrian, “some by voice, some by visible signals, and some by trumpet.” [Arr.,

TH

, 27]

Originally, the Roman military standard was merely a pole around which hay was wound, used as a visual rallying point for soldiers in battle and as a method of signaling commanders’ orders. The republican consul Marius made the eagle, a bird sacred to Jupiter, sole symbol of the legion. Previously, wolves, bears, horses, minotaurs and eagles had all been used. The eagle standard of the legion, the aquila, initially silver,

later gold, was a religious as well as a practical symbol endowed with huge mystical significance for Romans. The recovery of “eagles” lost to the enemy was a celebrated event which added luster to the reputations of generals responsible.

The eagle standard was considered, said Dio, to be “a small shrine.” It led the legion’s 1st Cohort, whose job it was to defend it, and always remained with the legion commander. “It is never moved from the winter quarters unless the entire army takes the field,” said Dio. “One man carries it on a long shaft which terminates in a sharp spike so that it can be set firmly in the ground.” [Dio,

XL

, 18] Long after the fall of the Roman Empire, the eagle which had symbolized her greatness would be taken up as a national symbol by countries such as Germany, Russia, Poland and the USA, and used by the Roman Catholic Church.

Each maniple of the legion also had its own standard. The manipular standard had a raised hand on top—

manipulus

means “a handful.” Each imperial standard bore an

imago

, a small round ceramic portrait of the ruling emperor, and frequently of the empress of the day and other exalted personages. Legion standards also bore the unit emblem, a symbol representative of its zodiacal birth sign, plus devices depicting bravery decorations awarded to the unit, and symbolic grass tufts.

On the march and in formal processions, the standards preceded the troops, bunched together. The legion’s standards were planted at the center of both winter

and marching camps, and even the ground they occupied was considered sacred. They formed part of an altar that included statues of the emperor. Placed outside the standard-bearer’s quarters, it was illuminated at night by burning torches.

The Praetorian Guard used the image of Victoria, winged goddess of victory, on their standards. Auxiliary cohorts and alae used animals on their standards, including the boar and lion. Prior to the commencement of military campaigning every year, a religious ceremony called the

lustratio exercitus

, or lustration exercise, was performed, where Roman military standards were purified, dressed with garlands and sprinkled with perfumed oil, and animal sacrifices performed. Traditionally this took place in Rome between March 19 and 23, but in the field could be performed at other times.

Roman standards were focal points for the attacking enemy, who particularly went after the golden aquila. To lose its eagle was the single greatest disgrace for a legion. The 5th Alaudae, 12th Fulminata and 21st Rapax legions all suffered this fate.

IX. THE VEXILLUM

Detachments from a legion marched under a

vexillum

, a square cloth banner, bearing the unit’s number and title. Such detachments were called vexillations. A remnant of a vexillum found in Egypt was made of coarse linen, dyed scarlet. It has a decorative fringe at the bottom and a hem at the top to receive the transverse bar that held it. This vexillum carries an image in gold of Victoria, goddess of victory, standing on a globe. It may have been related to the Praetorian Guard and a visit to Egypt by an emperor such as Hadrian or Septimius Severus. [Web., 3]

X. THE DRACO, OR DRAGON STANDARD

Following the Dacian Wars of

AD

101–106, Roman cavalry units increasingly adopted the Dacian-style dragon standard. The

signum draconis

, or “draco,” consisted of a wood or bronze dragon’s head on a pole, from which draped a long “body” made

of several lengths of dyed cloth sewn together. As the draco’s bearer galloped along, the body filled with air and trailed behind him, to great visual effect. A device in the dragon’s mouth made it howl as the wind passed through it. Arrian indicates that by the first half of the second century, the draco was used by all Roman mounted units.

XI. THE COMMANDER’S STANDARD

Each Roman army commander had his own standard. In the early imperial era standards were large square banners with purple letters on them identifying the army and its commander-in-chief.

In camp, the general’s standard remained in his praetorium. When there was disturbance in Germanicus Caesar’s camp at Cologne in

AD

14, rebellious troops forced their way into his praetorium and forced him to give up his standard to them. [Tac.,

A

, 1, 39] When a general raised his standard in camp, this was the signal to prepare for battle. It therefore needed to be large enough to be seen from a distance.

On the march, the general’s standard could be fixed to a packhorse. Famously, the horse carrying the standard of Caesennius Paetus bolted while his army was crossing the Euphrates river in

AD

62. It was seen as a bad omen at the time, for Crassus’ standard had reportedly blown into the river when he was crossing the Euphrates in 53

BC

on his way to disaster at Carrhae. The

AD

62 incident presaged the humiliating retreat of Paetus’ army from Armenia months later. [Dio,

XL

, 18]