Legions of Rome (7 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

After

AD

268, under the decree of Galienus, praetors no longer held commands.

Propraetor was the title given to governors of imperial Roman provinces—as opposed to proconsul, the title given to “unarmed” senatorial provinces, whose governors were appointed by the Senate.

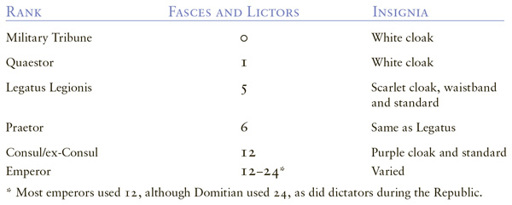

XXIV. SENIOR OFFICER RANK DISTINCTIONS

Early Imperial Roman Army

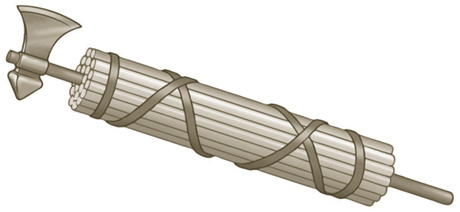

The fasces, bundles of wooden rods around an ax, signified the power of the Roman magistrate.

XXV. SENIOR OFFICERS OF THE LATE EMPIRE

Prefects, dukes and counts take command

During the reign of co-emperor Diocletian (

AD

285–305), Rome’s original provinces were divided into more than a hundred smaller provinces, each with their own governor and military commander. Between

AD

312 and 337 Constantine the Great took this reorganization further.

With prefects commanding legions, senior tribunes continued to be second-in-command of legions, on the emperor’s direct appointment. A “second tribune” replaced the old enlisted rank of camp-prefect as third-in-command of a legion, and was given the appointment on merit after lengthy service. [Vege.,

II

]

Thin-stripe tribunes were replaced as officer cadets by the

candidati militares

, the military candidates. Under Constantine, this officer training corps comprised two cohorts attached to the emperor’s bodyguard. Wearing white tunics and cloaks,

candidatores

, as they were called, were all young men chosen for their height and good looks. Candidati service prepared suitable trainee officers for promotion to tribune and unit commands. On several occasions in the fourth century, the candidates militares went into battle with their emperors, serving as independent fighting units within the imperial bodyguard.

The fourth-century provincial governor was a civilian. Separate provincial military commanders held the rank of

dux

, or “leader,” the latter-day duke. The duke’s superior was a regional commander whose authority might extend across several provinces, or even in some cases the entire east or west of the empire, holding the rank of

comes

, literally meaning “companion” of the emperor, the latter-day count. Counts also had charge of areas of civil administration. Military

comites

also commanded the household guard. In the late fourth century there were always two military counts and thirteen dukes in the west of the Roman Empire, while in the east there were four military counts and twelve dukes.

Both duke and count were distinguished when in armor by a golden

cincticulus

, the general’s waistband, as opposed to the scarlet cincticulus of legion legates of old. The duke and count received generous salaries as well as allowances that provided each with 190 personal servants and 158 personal horses. In place of the two praetorian prefects, Constantine introduced the posts of master of

infantry and master of horse as the empire’s supreme military commanders. The post of praetorian prefect was retained, but in a civil administrative role, with several stationed throughout the empire as financial auditors reporting directly to their emperor. [Gibb.,

XVII

]

Many fourth- and fifth-century Roman commanders had foreign blood, among them the counts Silvanus and Lutto, both Franks; Magnentius, a German; Ursicinus, who was probably an Alemanni German; and Stilicho, one of whose parents was a Vandal. The father of Count Bragatio, Master of Horse under Constantius II, was a Frank. Mallobaudes, who was a tribune with the

armaturae

, a heavy-armored element of the Roman household cavalry in the fourth century, was a Frank by birth, and went on to become king of the Franks. Victor, Master of Horse under the emperor Valens, was a Sarmatian.

XXVI. AUXILIARIES

The auxiliary was a foreign soldier who did not originally hold Roman citizenship. Most provinces and a number of allied states supplied men to fill auxiliary units of the Roman army. Some auxiliary units lived and fought alongside particular legions; others operated independently. In the

AD

60s, for example, eight cohorts of Batavian light infantry were partnered with the 14th Gemina Legion.

At least two wings of auxiliary cavalry would also march with a specific legion, so that a legion, with its auxiliary support, would typically take the field with around 5,200 legionaries and a similar number of auxiliaries, creating a fighting force of 10,000 men. In the first century, it was assumed that a legion would always march with its regular auxiliary support units—Tacitus, referring to reinforcements received by Domitius Corbulo in the East in

AD

54, described the arrival of “a legion from Germany with its auxiliary cavalry and light infantry.” [Tac.,

A

,

XIII

, 35]

Independent auxiliary units provided the only military presence in so-called “unarmed” provinces—Mauretania in North Africa, for instance, was for many years only garrisoned by auxiliaries.

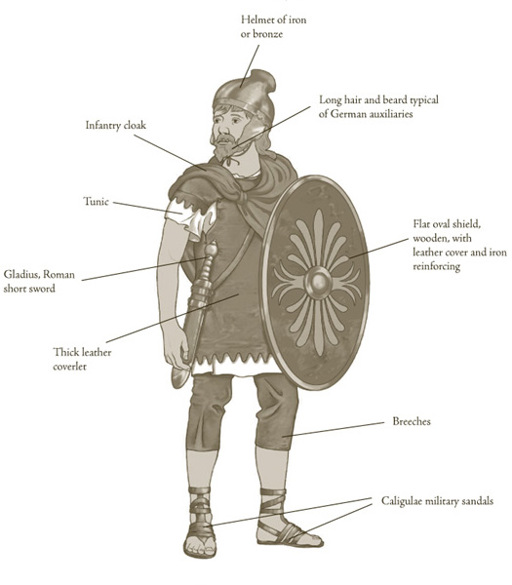

Although often armed in a similar manner to legionaries, auxiliaries wore breeches, sported light ringmail armor, and were referred to as “light infantry.” Specialist units such as archers, and slingers firing stones and lead shot, were always auxiliaries. Syria provided the best bowmen, while Crete and Spain’s Balearic Isles were famous

for their slingers. Each legion had a small cavalry component of 128 men, as scouts and couriers, but auxiliaries made up all the Roman army’s independent cavalry units. Germans, and in particular Batavians, were the most valued cavalry.

Auxiliary

Light Infantry Soldier

Early second century (taken from Trajan’s column).

The auxiliary was paid just one third of the salary of the legionary; 300 sesterces a year until the reign of Commodus, when it increased to 400 sesterces. [Starr,

V

.

I

]

The auxiliary also served for longer—twenty-five years, as opposed to the legionary’s sixteen- and later twenty-year enlistment (plus Evocati service). Once discharged, auxiliaries could not be recalled. They did not receive a retirement bonus, but both auxiliaries and seamen received an enlistment bonus, the

viaticum

, on joining the service, of 300 sesterces. [Ibid.]

From Britain to Switzerland, and from the Balkans to North Africa, tribes were responsible for supplying recruits for their particular ethnic auxiliary units, although there were occasional exceptions. Tiberius decreed that new recruits to the Thracian Horse would come from outside Thrace, much to the aggravation of the proud men of the existing Thracian Horse.

Copies of every individual patent of citizenship issued to discharged auxiliary soldiers were kept at the Capitoline Hill complex at Rome in the Temple of the Good Faith of the Roman People to its Friends. The auxiliary prized his certificate of citizenship; some had themselves depicted on their tombstones holding it. In

AD

212, Commodus made Roman citizenship universal, eliminating citizenship as an incentive for auxiliary service.

A typical auxiliary who served his twenty-five years and gained his citizenship was Gemellus from Pannonia, who joined up in

AD

97 during the reign of Nerva, and was granted his citizenship on July 17,

AD

122 in the reign of Hadrian. Just as a legionary could be transferred between the legions with promotion, auxiliaries moved between different units. When Gemellus received his honorable discharge, he was a decurion with the 1st Pannonian Cohort. His career had seen him work his way from 7th cohort to 1st, serving in units from the Balkans, France, Holland, Spain, Switzerland and Greece, including a stint with the 7th Thracian Cohort in Britain.

Even after they obtained their citizenship, auxiliaries frequently signed up for a new enlistment. Lucius Vitellius Tancinus, a cavalry trooper of the Vettonian Wing, born at Caurium in Spain, joined the army at the age of 20, served his twenty-five-year enlistment in Britain, obtained his citizenship, then signed on for another term. A year later, at the age of 46, he died, probably seeking a cure for whatever ailed him at the Temple of Aquae Sulis in Bath, the waters of which had legendary healing powers.

During most of the imperial era, auxiliary units were commanded by prefects, always members of the Equestrian Order, and frequently young gentlemen of Rome. But in some cases, auxiliary units were commanded by nobles from their own tribe. These ethnic prefects were rarely permitted to rise above prefect rank.

A BRITISH AUXILIARY EARNS EARLY RETIREMENT

The reward for brave service for Rome

On August 10,

AD

110, Novanticus, a foot soldier born and raised in the town of Ratae, modern-day Leicester in England, was standing at assembly in a Roman army camp at Darnithethis in recently conquered Dacia. Novanticus was a Celtic Briton. He and some 1,000 other young Celts had joined the Roman army in the spring of

AD

98, enrolled by the recently enthroned emperor Trajan in a new auxiliary light infantry unit honored with the emperor’s family name: the

Cohors I Brittonum Ulpia

, or 1st Brittonum Ulpian Cohort.

Three years later, the 1st Brittonum had been one of many units in the 100,000-man Roman army that had invaded Dacia. Novanticus and his British comrades had fought so fiercely and so bravely in the bitterly contested battles in the mountains and passes of Dacia, that, four years after the country had been conquered, the emperor granted all the surviving members of the unit honorable discharges, thirteen years before their twenty-five-year enlistments were due to expire.

At assembly, Novanticus presented himself before his commanding officer and was handed a set of bronze sheets just large enough to fit in one hand. This was the Briton’s discharge certificate, a copy of which would go to Rome to be displayed with hundreds of thousands of others. With discharge, Novanticus received the prize of Roman citizenship. With citizenship, he could take a multipart Roman name. Novanticus chose a name that honored the emperor he had loyally served for the past twelve years.

“To the foot soldier Marcus Ulpius Novanticus, son of Adcobrovatus, of Ratae,” the commander read, “for loyal and faithful service in the Dacian campaigns, before the completion of military service.” [

Discharge certificate of Marcus Ulpius Novanticus, British Museum

]

Marcus Ulpius Novanticus would return home to Britain to enjoy the fruits of his military service and raise a family. Nearly 2,000 years later, his bronze discharge certificate would emerge from the British earth to tell of his part in the Roman war machine.

XXVII. THE USE OF MULTIPART NAMES BY ROMAN AUXILIARIES AND SAILORS

Until

AD

212, when Commodus introduced universal Roman citizenship, auxiliaries, marines and seamen in the Roman navy were not Roman citizens. Non-citizens, so-called

peregrines

, traditionally only used a single name—Genialus, for example. A Latin multipart name such as Gaius Julius Genialus was the preserve of those with the Latin franchise. Accordingly, students of Roman history, from the famous nineteenth-century German scholar Theodor Mommsen onwards, came to assume that anyone recorded with a multipart name had to be a Roman citizen. But, as Professor Chester Starr and others point out, non-citizens serving in the Roman military not infrequently used Latin names, and consequently the legal status of a Roman soldier or sailor cannot always be ascertained from their name. [Starr,

V. I

]