Life in a Medieval Castle (3 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

or miner, and the battering ram, and afforded shelter to attackers in the form of “dead ground” that defensive fire could not reach. The Byzantines and Saracens were the first to build circular or multiangular towers, presenting no screen to the enemy at any point. But the rectangular plan remained more convenient for organizing interior space, and the European transition was gradual. For a while engineers experimented with keeps that were circular on the outside and square on the inside. Or keeps were built closely encircled by a high wall called a chemise. Entry was by a gateway in the chemise, from which one climbed a flight of steps against its interior face, and the steps led to a wall walk, which was connected to the keep by a bridge or causeway with a draw section. The drawbridge might be pulled back on a platform in front of the gate, or it might be hinged on the inner side and raised by chains on the outer so that when closed it stood vertically against the face of the gate, forming an additional barrier. Or it might turn on a horizontal pivot, dropping the inner section into the pit while the outer rose to block the gateway. An attacking

enemy had to force the gate, climb the stairs, follow the wall walk, and defile across the causeway, exposed to attack from all directions.

The Tour de César in Provins, east of Paris, built in the middle of the twelfth century on the mound of an earlier motte-and-bailey, had a keep that was square below and circular above, the two elements joined by an octagonal second floor. Four semicircular turrets rose from the corners of the base, while a battlemented chemise ran around the edge of the mound and down into the bailey. Entrance was by a vaulted stairway up the mound leading to the chemise, whence a causeway and drawbridge connected with the tower itself.

Other elaborations appeared. Vertical sliding doors, or portcullises, oak-plated and shod with iron, and operated from a chamber above with ropes or chains and pulleys, enhanced the security of gateways. Machicolations—over-hanging projections built out from the battlements, with openings through which missiles and boiling liquids could be dropped—were added, at first in wood, later in stone. The curtain walls were protected by towers built close enough together to command the intervening panels. Arrow loops, or

meurtrières

(“murderesses”), narrow vertical slots, pierced the curtains at a level below the battlements. Splayed, or flared to the inside, these gave the defending archer room to move laterally and so cover a broad field of fire while presenting only the narrow exterior slit as a target. A recess on the inner side sometimes provided the defender with a seat.

By the later twelfth century, older castles were being renovated in the light of the new military technology. Henry II gave Dover a great rectangular inner keep with walls eighty-three feet high and seventeen to twenty-one feet thick, with elaborate new outworks. At Chepstow the castle’s most famous owner, William Marshal, built a new curtain wall, with gateway and towers, around the eastern

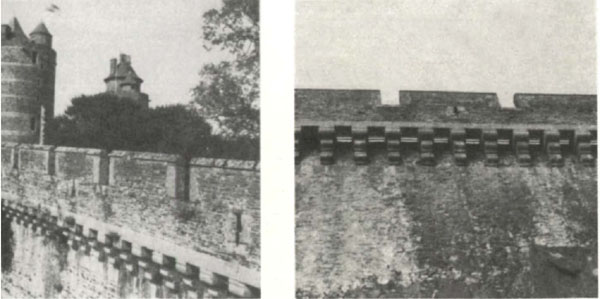

Fougères, Brittany: Thirteenth-century curtain wall, showing crenelations and machicolations; Melusine and Gobelin Towers of the thirteenth and fourteenth century in the background. Right, machicolations of curtain wall seen from below, showing spaces through which missiles could be dropped.

bailey, one of the earliest defenses in England to use round wall towers and true arrow loops. In the second quarter of the thirteenth century William’s sons added the barbican on the west, defended by its own ditch and guarded by a tower. On the east they built a large new outer bailey, with a double-towered gatehouse closed by two portcullises and defended by two lines of machicolations. A successor, Roger Bigod III, completed the fortifications by building the western gatehouse, finished about 1272, to protect the barbican, and constructing the great Marten’s Tower at the southeast corner of the curtain walls, begun about 1283 and completed in the 1290s. Increased security permitted the building of the new range of stone domestic buildings along the north wall, including a spacious great hall, completed in time for a visit by Edward I in December 1285.

New castles built in the thirteenth century showed even more clearly the impact of Crusader experience. They were sited wherever possible on the summit of a hill, with the inner bailey backed against the more precipitous side, and

Fougeres, Brittany: arrow loop in the Melusine Tower.

the main defense was constructed to face the easier slope. Two or three lines of powerful fortifications might front the approach side, making it possible, as at Chepstow, to abandon the keep as a residence for more comfortable quarters in the secure bailey. These quarters were often built of timber, while the stone keep, now usually round, and smaller but stronger, became the last line of defense and served during a siege as the lord’s or castellan’s command post. Stairways and passages, sometimes concealed, facilitated the movement of defense forces. Occasionally the keep was isolated within its own moat, spanned by a drawbridge, and encircled by a chemise.

In a final period, from about 1280 to 1320, some of the most powerful castles of any age or country were built in Great Britain—mainly in Wales—by Edward I. From his cousin Count Philip of Savoy, Edward borrowed an engineering genius named James of St. George, who directed a staff of engineers from all over Europe and a work force that at times numbered up to fifteen hundred. James received an excellent salary, plus life pensions for himself and his wife.

James kept the outworks of his castles strong, but concentrated the main defense on a square castle enclosed by two concentric lines of walls with a stout tower at each

corner of the inner line. The keep now disappeared, rendered superfluous by the elaborate towers and gatehouses which could hold out independently even if the enemy won the inner bailey. Multiple postern gates, protected by outworks, increased flexibility. At Conway, James followed the contour of a high rock on the shore of an estuary with a wall and eight towers, and a gateway at either end protected by a barbican. Within, a crosswall divided the castle into two baileys, the outer containing the great hall and domestic offices of the garrison, the inner the royal apartments and private offices. Access was by a steep stairway over a drawbridge and through three fortified gateways under direct fire from towers and walls on every side. Caernarvon, Harlech, Flint, Beaumaris, and Denbigh

Launceston Castle, Cornwall: Shell keep built in the twelfth century by erecting a stone encircling wall on an eleventh-century motte. The round inner tower was added in the thirteenth century. (Department of the Environment)

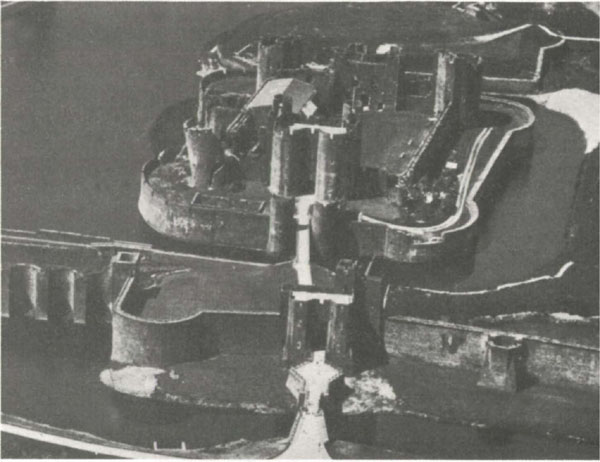

Caerphilly Castle, Wales: Built during Edward I’s conquest of Wales, on an island in a lake, Caerphilly is protected by two concentric enclosures with two powerful gatehouses at both east and west. On the more vulnerable eastern side (foreground), still a third defense was built—a long wall that dammed the entire lake and enclosed a barbican, with its own gatehouse, connected with the castle by a drawbridge. (Department of the Environment)

likewise had defenses skillfully adapted to their sites. All were built along the coast of North Wales, the wild country where the stubborn Welsh put up their stoutest resistance. In South Wales the magnificent castle of Caerphilly was built (1267-77) by Richard de Clare, earl of Gloucester, whose family had once owned Chepstow. Caerphilly’s site, as picturesque as it was defensible, was on an island in a lake, surmounted by a double line of walls equipped with four powerful gatehouses, and protected by a moat and barbican with a fifth gatehouse.

Thus the castle, born in tenth-century continental Europe as a private fortress of timber and earthwork, brought to England by the Normans, converted to stone in the shell keeps and rectangular keeps of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, refined and improved by engineering knowledge from Crusading Syria, achieved its ultimate development at the end of the thirteenth century in the western wilds of the island of Britain.

The Lord of the Castle

S

AXON

E

NGLAND, NEARLY DEVOID OF CASTLES

, was also devoid of most of the social and economic apparatus that typically produced the castle. “Feudalism,” the term given by a later age to the dominant form of society of the Middle Ages, had in 1066 hardly made its appearance on the island of Britain. In the homeland of the Norman invaders, on the contrary, feudalism was well developed in all its aspects. These consisted of the sworn reciprocal obligations of two men, a lord and a vassal, backed economically by their control of the principal form of wealth: land. The lord—the king or great baron—technically owned the land, which he gave to the vassal for his use in return for the vassal’s performance of certain services, primarily military. The vassal did not work the land himself, but gave it over to peasants to work for him under conditions that by the High Middle Ages had become institutionalized.

William and the Normans brought feudalism to England, not only because it was the social and political form they were accustomed to, but because it suited their needs in the conquered territory. William in effect laid hold of all the land in England held by secular lords—arable, forest, and swamp; took a generous share (about a fifth) for his own royal demesne; and parceled out the rest to his lay vassal followers in return for stated quotas (“fees”) of knights owed him in service. The Church, which had backed the Conquest, was left in undisturbed possession of its lands, though prelates owed knights’ service the same as lay lords. William’s eleven chief barons received nearly a quarter of all England. Such immense grants, running to hundreds of square miles of domain, implied “subinfeudation,” again the term of a later age, in which the great vassal of the king became in turn the lord of lesser vassals. In order to produce the military quota he owed the king, the lord gave his vassals “knights’ fees” (fiefs) in return for their service. By the accession of Henry I in 1100 this process was far advanced, and England had become, if anything, more feudal than Normandy.

Splendidly representative of the great Norman barons of the twelfth century were the lords of Chepstow Castle. After the disgrace and imprisonment of William Fitz Osbern’s son Roger, the royal power had retained possession of Chepstow, but sometime prior to 1119 Henry I granted it, with all its vast dependencies, to Walter de Clare, a kinsman and loyal stalwart of the king. Walter, remembered for founding Tintern Abbey, one of the greatest of the great English medieval monasteries, was succeeded at Chepstow by his nephew Gilbert Fitz Gilbert de Clare, who aggressively extended the family’s Welsh holdings and in 1138 was made earl of Pembroke. Gilbert, surnamed Strongbow, plotted and took arms against the royal power, but turned around and came to terms with it, marrying the king’s mistress, Isabel of Leicester. Their son. Richard Fitz Gilbert, also

surnamed Strongbow, became one of the most renowned of all the famous Norman soldier-adventurers of his age. In 1170 this second Strongbow conquered the greater part of Ireland, taking Waterford and Dublin and restoring to power King Dermot MacMurrough of Leinster, in return for Dermot’s daughter Eve and the bequest of his kingdom. On Dermot’s death Strongbow made good his conquest by defending Dublin against a two-month siege by a rival Irish king, and demonstrated his loyalty (and political sagacity) by arranging to do homage for his conquest to the new king of England, Henry II (Plantagenet).

Strongbow’s only son dying in childhood, his daughter Isabel became heiress for the immense holdings of the Clare family in western England, Wales, and Ireland. The choice of Isabel’s husband, the new lord of Chepstow, was of obvious moment to the royal power. Henry II exercised his feudal right as lord with his habitual prudence, and Isabel was betrothed to a landless but illustrious supporter of the Crown, Guillaume le Maréchal, or William Marshal, the most admired knight of his day, and a prime example of the upward mobility that characterized the age of the castle.

William Marshal’s grandfather had been an official at the court of Henry I. His name was simply Gilbert;

maréchal

(“head groom”) was the name of his post. The office was sufficiently remunerative for Gilbert to defend it against rival claimants by judicial duel, and for his son John, William’s father, to go a step farther and successfully assert by judicial combat that the job was hereditary. Following his victory John assumed the aristocratic-sounding name of John Fitz Gilbert le Maréchal.

In the chronicle of the civil war between Stephen of Blois (nephew of Henry I) and Matilda of Anjou (Henry I’s daughter) over the English throne, John le Maréchal, or John Marshal, won mention as “a limb of hell and the root of all evil.” Two instances of his hardihood especially drew the notice of the chroniclers. Choosing Matilda’s side in the

war, John at one moment found himself in a desperate case: to cover Matilda’s retreat from a pursuing army he barricaded himself in a church with a handful of followers. Stephen’s men set fire to the church, and John, with one companion, climbed to the bell tower. Though the lead on the tower roof melted and a drop splashed on John Marshal’s face, putting out an eye, he refused to surrender, and when his enemies concluded that he must be dead in the smoking ruins, made good his escape.

A few years and many escapades later John was prevailed upon to hand over his young son William to the now King Stephen as a hostage against a possible act of treachery during a truce. John then went ahead and committed the treachery, reinforcing a castle the king was besieging. King Stephen threatened to hang young William unless the castle surrendered. The threat had no effect on John, who coolly answered that he did not care if his son were hanged, since he had “the anvils and hammer with which to forge still better sons.”

The lad was accordingly led out next morning toward an oak tree, but his cheerful innocence won the heart of King Stephen, a man of softer mold than John Marshal. Picking the boy up, the king rode back to camp, refusing to allow him to be hanged, or—an alternative proposal from the entourage—to be catapulted over the castle wall. The king and the boy were later found playing “knights” with plantain weeds and laughing uproariously when William knocked the head off the king’s plantain. Such tenderheart-edness in a monarch was almost as little admired as John Marshal’s brutality,

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

succinctly observing of Stephen that “He was a mild man, soft and good, and did no justice.”

Thanks to Stephen’s lack of justice, William Marshal was permitted to grow up to become the most distinguished of all the lords of Chepstow Castle and the most renowned knight of his time. Gifted with his father’s soldierly prowess

but free of his rascally character, William first served King Stephen and afterward his Plantagenet successor, Henry II (son of the defeated Matilda of Anjou), from whom he received Chepstow along with Isabel de Clare, the “

pucelle

[damsel] of Estriguil, good, beautiful, courteous and wise,” according to William’s biographer. The gift was confirmed by Henry’s successor, Richard the Lionhearted, who generously (or sensibly) overlooked a past episode when William had fought Richard during the latter’s rebellion against his father. As a member of the royal council, William served Richard and Richard’s brother John for many years and played a leading—perhaps the leading—role in negotiating Magna Carta. On John’s death he efficiently put down the rebel barons supporting Prince Louis of France and during a reluctant but statesmanlike term as regent established the boy Henry III securely on the throne.

William was succeeded as lord of Chepstow and earl of Pembroke by each of his five sons, one after the other. William Marshal II died in 1231, and was succeeded by his brother Richard, who was murdered in Ireland in 1234, possibly at the instigation of Henry III. The third son, Gilbert, died in 1241 from an accident in a tournament at Hertford. Four years later Walter Marshal succumbed, and was outlived by the fifth brother, Anselm, by only eight days. Thus was fulfilled a curse pronounced at the time of their father’s death by the bishop of Fernes in Ireland. William had seized two manors belonging to the bishop’s church, and the bishop had pronounced excommunication. The sentence had no effect on William Marshal, but it troubled the young king Henry III, who promised to restore the manors if the bishop would visit William’s tomb and absolve his soul. The bishop went to the Temple, where William was buried, and in the presence of the king and his court addressed the dead man, as Matthew Paris commented, “as if addressing a living [person]. ‘William, if the possessions which you wrongfully deprived my church of be

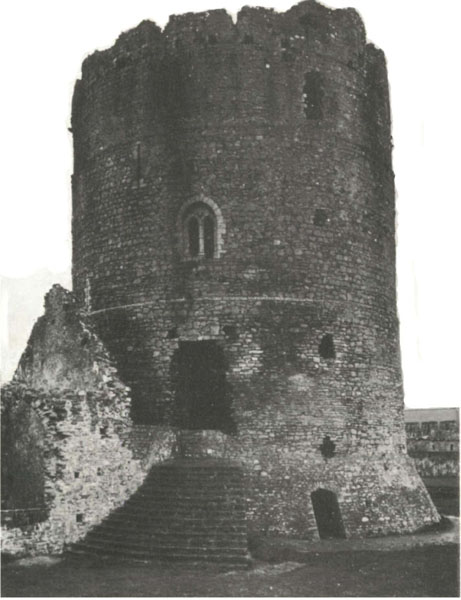

Pembroke Castle, Wales: Round keep built by William Marshal about 1200. (Department of the Environment)

restored…I absolve you; if otherwise, I confirm the said sentence that, being enmeshed in your sins, you may remain in hell a condemned man for ever.’” The king, though annoyed by the bishop’s response, asked William Marshal II to return the manors. William refused, his brothers upheld his position, the young king abandoned his attempt at reconciliation, and the bishop pronounced his curse: “‘In one generation his name shall be destroyed’ [in the words of the psalm] and his sons shall be without share in that benediction of the Lord, ‘Increase and multiply!’ Some of them will die a lamentable death, and their inheritance will be scattered.” Chepstow passed out of the family by way of William’s daughter Maud, who inherited after the death of Anselm in 1245.

On Maud’s death in 1248, the royal power had no hand in settling the ownership of Chepstow because Maud had been a widow with grown sons. Her husband had been a Bigod, a Norman family that had risen to prominence after the Conquest. The new lord of Chepstow was Maud’s oldest son, Roger Bigod, who also had the title of earl of Norfolk, and who now acquired the unique one of “earl marshal of England,” an honor won by William Marshal and now officially made hereditary. The name “marshal” thus completed a cycle from designation of a job to surname to title of nobility.

Had the king been able to choose Maud’s husband, he might well have passed over the Bigods, one of the most unruly families in the kingdom. Roger Bigod proved true to the tradition of his own forebears rather than to that of loyalist William Marshal. Roger joined Simon de Montfort’s rebellion that wrested control of the government from Henry III, then changed sides and fought against Montfort at the battle of Lewes in 1264. Roger was succeeded by his nephew, also named Roger, who turned once more against the royal power, which he battled for many years.

Although one of their characteristics worth noting is individuality—William Marshal contrasted with the Bigods—the lords of Chepstow share a number of traits that may be taken as those of the great English lord of the High Middle Ages, and to a considerable degree, those of European lords in general. One, relatively superficial, is their Frenchness. The Clares, Marshals, and Bigods, French in origin, continued to speak French, the language of the elite, for several generations. They were French in other ways, as were the Flemish, Spanish, and German barons of the same period, France supplying not only the language of the nobility but the style—the Crusade, the

chanson de geste

, the trouvère and troubadour poetry, the tournament, the castle, the cathedral architecture.

A more deeply ingrained trait of the lords of the castles was their love of land. Even more than their much-advertised love of fighting, their dedication to getting, keeping, and enlarging their estates dominated their lives. Estate management itself, even on a smaller scale than Chepstow, was extremely demanding. No lord, however fond of fighting, could afford to neglect his estates. Many twelfth-and thirteenth-century lords passed up perfectly good wars and even stubbornly resisted participating in them because it meant leaving their lands. Few English lords, and by the thirteenth century few Continental lords, participated in the distant Crusades; they left the Holy Land to be defended mainly by Knights Templars and mercenaries. English barons even objected strenuously to fighting in defense of their king’s French territories. Roger Bigod, future lord of Chepstow, and others accompanied Henry III to France only reluctantly in 1242, seizing the earliest opportunity to protest that the king had “unadvisedly dragged them from their own homes.” whither they at once returned.

Land was the basis of lordship, and living on, by, and for

the land had an undoubted influence on the lord’s personality. He drew his revenues from it, and used his nonfarming lands for hunting.

Politics certainly interested the lord, but nearly always because of its relation to land economics. If the sovereign’s demands grew excessive, or if self-interest dictated, the baron seldom hesitated to take up arms in rebellion, his feudal oath notwithstanding. He sat on the king’s council and attended what in the thirteenth century was beginning to be called parliament, partly to help the king make decisions, but mainly to look out for his own interests.

Between politics and estate management, the lord’s days were typically crowded. Far from loafing in his castle during the intervals between wars, he scarcely found time to execute his many functions. At Chepstow, where the Fitz Osberns and Clares were “marcher” earls, enjoying the power that went with guarding the frontier, and where the later Marshals and Bigods had the distinction of the title of earl marshal, they exercised major functions: police, judicial, and fiscal. Such powers, delegated to the marcher earls by the king, gave them much of the independent status enjoyed by the great Continental dukes, counts, and bishops, who paid only nominal allegiance to their sovereigns and even possessed such regalian rights as that of coinage.