Life in a Medieval Castle (4 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

Most Norman barons of England were much more tightly circumscribed by the authority of the Crown. In 1086, in the setting of Roman-walled Old Sarum, William the Conqueror accepted homage and fealty from “all the landholding men of any account,” that is, not only the barely two hundred tenants-in-chief but the barons’ vassals. William’s successors continued to encroach on baronial prerogatives. The criminal jurisdiction that traditionally belonged to large landholders was gradually usurped by the Crown. Under Henry II the Curia Regis, the royal council, assumed the role of an appeals court, as did the king’s eyre

(itinerant justices), whose visits to the shires to settle property suits were regularized by the later years of Henry II.

Henry II also gave decisive impetus to the jury system, which after 1166 was regularly employed to investigate crimes and to settle important civil cases. The law dispensed was a mixture of the old codes of the Saxon kings, feudal custom brought over from Normandy, and new decrees. Judgments were severe: Thieves were hanged, traitors blinded, other offenders mutilated. Sometimes a criminal was drawn and quartered. Prisoners might be confined in a castle tower or basement to await ransom or sentencing, but rarely as punishment, prison as punishment being little known in the Middle Ages. The term “dungeon” (from donjon) as a synonym for prison dates from a later era when many castles were so employed.

Though justice was summary, it was not unenlightened. Torture was not often employed even to extract confessions from thieves, confession hardly being needed if the man was caught with the goods. The records of many court cases, both civil and criminal, reveal considerable effort to determine the truth, and not infrequently a degree of lenience. By the thirteenth century the worst of the ancient barbarian legal practices were being abandoned. In 1215 the Lateran Council condemned trial by ordeal, in which a defendant strove to prove his veracity by grasping a red-hot iron without seriously burning his hand or by sinking when thrown into water, and in 1219 the custom was outlawed in England. Judicial combat, by which the defendant or his champion fought the accuser, survived longer.

On the Continent, justice was divided into high and low, with administration of high justice, comprising crimes of violence, arson, rape, kidnapping, theft, treason, counter-feiting, and false measure, generally held by the largest feudatories—kings, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots, and other great lords. The complications of the feudal system led

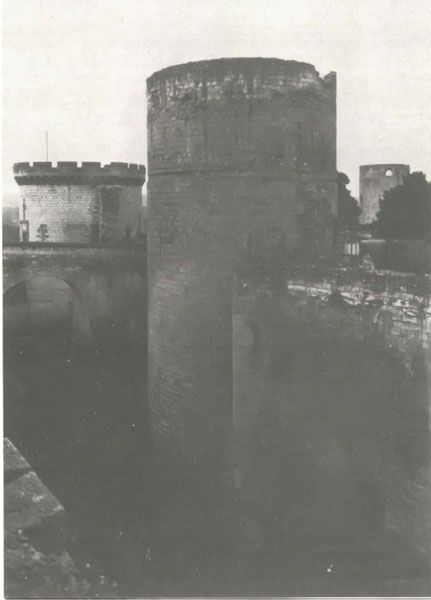

Chinon, on the Vienne, France: The Château du Coudray, separated from the rest of the castle by a wide moat; in the foreground the Tour du Coudray, a round keep built by Philip Augustus in the thirteenth century. The Templars were held for trial here in 1308. (Archives Photographiques)

to many special arrangements by which a lord might retain low justice, give it up to another lord, or keep only the money fines and give up the confiscations of property. Great lords, of course, did not preside over their own courts either in England or on the Continent, but were represented by provosts and seneschals.

Robbed of much of their judicial power, and thus of important revenues from the fines and confiscations, the English barons sought to compensate by acquiring posts in the royal government. The most important was that of justiciar of the realm, created by Henry I, made permanent as a kind of prime minister by Henry II, and disappearing in the thirteenth century. Other great officers of state included the chancellor, the chamberlain, the treasurer, the marshal, and the constable, backed by lesser or assistant justiciars and a throng of subordinate officials. On the local level, William the Conqueror had found an ideal policing instrument in the old Anglo-Saxon post of sheriff, chief officer of the shire (county), and had entrusted it throughout the country to his Normans.

William began by choosing his officials from among his greatest barons, such as Chepstow’s William Fitz Osbern. But the tendency of many of these men, made doubly powerful by possessions and official posts, to assume independent power, induced a change of policy. Young Henry III had as his chief justiciar Hubert de Burgh, a member of a knightly family of moderate means, who acquired nearly dictatorial powers and immense wealth that apparently led to his downfall in 1232. The office of justiciar was then left vacant, and its powers passed to the chancellor.

The sheriffdom, or shrievalty, was even more a focus of conflict as the fractious barons strove to occupy it themselves or place it in friendly local hands. By the thirteenth century the office had become one of the most embattled prizes of the baronial-royal conflict. Loyal William Marshal served the king ably and faithfully as sheriff (as well as

marshal, assistant justiciar, and regent), but he was an exception. More typical was ambitious, rebellious Falkes de Bréauté, who at one time held the sheriffdom in several different counties but was ultimately stripped of all office. After the baronial victory at Lewes in 1264, the barons replaced royal sheriffs wholesale, but following the royal victory at Evesham the next year, the barons’ men were all turned out again. Thus the sheriff’s office, which embraced important police, fiscal, and judicial functions on the county level, kept the English barons occupied in one way or another, either exercising the office or battling to control it.

On the Continent in the eighth century, the time of Charlemagne, the local government was administered in a unit much like the English one: the

pagus

or

comitatus

, counterpart of the English shire, and like the shire divided into hundreds (

centenae

), with local judicial and police powers. The court of the

pagus

was presided over either by the emperor’s official, the count, or by his deputy, the viscount, the French equivalent of the sheriff. But development on the Continent followed a very different course. By the twelfth century, the

pagi

and their courts had almost disappeared, their territory and jurisdiction taken over by local feudal lords, often descendants of the old local officials, whose offices had become hereditary. In the courts of these lords most of the judicial business of the land was conducted, and they exercised most of the police and military power. In the thirteenth century the French monarchy was steadily encroaching on the great feudatories by increasing the royal domain at their expense, but the process was far from complete. Lesser barons and knights found employment in both the royal and the feudal administrations, as viscounts, bailiffs, seneschals, provosts of a town, keepers of trade fairs, and many other offices.

The great lord, even with no official post, had more than

enough to occupy him in overseeing his estates and manors and making sure his household staff did not rob him.

Underlying the social, economic, and political position of the great lord, English or Continental, were always the two pillars of feudalism: vassalage and the fief. By the thirteenth century both were hallowed, even decadent institutions, their roots in a past so far distant that few lords could give an account of them.

Vassalage was the relationship to the lord, who for all the great English barons was the king. The fief was the land granted by the lord in return for the vassal’s service, or more technically, a complex of rights over the land which theoretically remained the legal possession of the lord.

The feudal relationship, which by the thirteenth century had accumulated a large train of embellishments, had originated as a simple economic arrangement designed to meet a military problem in an age when money was scarce. In late Roman times a custom had grown up whereby a man attached himself to a superior by an act of “commendation,” a promise of military service in return for support, often in the form of a grant of land known as a benefice. The Frankish Carolingian rulers of the eighth century rapidly expanded this custom to meet their need for heavily armed, mounted warriors, a need that arose from the new technique of war—mounted shock combat. The enhanced military value of the mounted warrior brought a corresponding rise in his social status, symbolized by a more personal relationship between lord and vassal. This more personal relationship was in turn symbolized by a new commendation ritual reinforced by an oath of fealty. In the commendation, the vassal placed his hands within the hands of the lord. The oath was sworn on a relic—a saint’s bone, hair, or scrap of garment—or on a copy of a Gospel. The contract entered into could not be lightly broken.

Charlemagne laid down precise and exceptional cases in

which the vassal might justifiably foreswear his oath: if the lord tried to kill or wound him, to rape or seduce his wife or daughter, to rob him of part of his land, or to make him a serf, or, finally, if he failed to defend him when he should. The lord had no absolute power over his vassal; if he accused the vassal of wrongdoing, he had to accord him trial in the public court, with the “jury of his peers.”

In Charlemagne’s time a vassal who owed military service, on horseback, with full equipment, needed a benefice amounting to from three hundred to six hundred acres, requiring about a hundred villeins to plow, plant, and harvest it. Although the land continued to belong formally to the lord, custom more and more favored the permanent retention of the land by the vassal’s family. The new vassal performed the commendation and oath as had his father. William Longsword, ancestor of William the Conqueror, on succeeding his father as duke of Normandy in 927, “committed himself into the king’s hands,” according to the chronicler Richer, and “promised him fealty and confirmed it with an oath.” An example of the renewal of vassalage following the death of the lord, as practiced in the twelfth century, is recorded by Galbert of Bruges at the time of the succession of William Clito as count of Flanders in 1127, when a number of knights and barons did homage to the new count:

“The count demanded of the future vassal if he wished without reserve to become his man, and he replied, ‘I so wish’; then, with his hands clasped and enclosed between those of the count, their alliance was sealed by a kiss.” The vassal then said: “I promise by my faith that from this time forward I will be faithful to Count William and will maintain toward him my homage entirely against every man, in good faith and without any deception.” Galbert concluded: “All this was sworn on the relics of saints. Finally, with a little stick which he held in his hand, the count gave investiture.”

Homage: The vassal puts his hands between those of his lord. (Bibliothèque Nationale. MS. Fr. 5899, f. 83v)

In England the oath of homage always contained a reservation of allegiance toward the king. A thirteenth-century English legal manual cites this formula:

With joined hands [the vassal] shall offer himself, and with his hands under his lord’s mantle he shall say thus—I become thy man of such a tenement to be holden of thee, to bear to thee faith of life and member and earthly worship against all men who live and can die, saving the faith of my lord Henry king of England and his heirs, and of my other lords—if other lords he hath. And he shall kiss his lord.

The ceremonial kiss was widely used, though it was less significant than the ritual of homage and the oath of fealty.

The vassal’s obligations fell into two large classes, passive and active. His passive obligations were to refrain from doing the lord any injury, such as giving up one of his castles to an enemy, or damaging his land or other property. The active duties consisted of “aid and counsel.” Under the “aid” heading came not only the prescribed military duty,

ost

or host, commonly forty days with complete equipment, either alone or with a certain number of knights, but a less onerous duty,

chevauchée

or cavalcade, which might mean a minor expedition, or simply escort duty, for example when the lord moved from one castle to another. In addition there was often the important duty of castle guard, and the further duty of the vassal to hold his own castle open to the

lord’s visit. Highly specialized services also appeared, ranging from the obligation of the chief vassals of the bishop of Paris to carry on their shoulders the newly consecrated bishop on his formal entry into Notre Dame, to that of a minor English landholder of Kent of “holding the king’s head in the boat” when he crossed the choppy Channel.