Life in a Medieval City (3 page)

Read Life in a Medieval City Online

Authors: Frances Gies,Joseph Gies

Tags: #General, #Juvenile literature, #Castles, #Troyes (France), #Europe, #History, #France, #Troyes, #Courts and Courtiers, #Civilization, #Medieval, #Cities and Towns, #Travel

But despite their advances the western cities continued to lag behind those of Italy. Twelfth-century Venice, Genoa, Pisa, and the other Italian maritime towns were sending out fleets of oared galleys that hauled the priceless spices of the Indies across the eastern Mediterranean; they were planting colonies on the shores of the Black Sea, fighting and bartering with the Moslems of Egypt and North Africa, giving powerful support to the Crusaders and taking valuable privileges in return, attacking the “Saracens” in their own backyards, and wresting from them islands and ports. Plunder helped build many of the truculent towers that sprouted in the Italian cities, from which wealthy and quarrelsome burghers defended themselves against their neighbors. In Pisa plunder contributed to the construction of a large tower designed to house the bells of a new cathedral; unfortunately this edifice did not settle properly. Venice crowned its Basilica of St. Mark with a huge dome, and built many other churches and public buildings. One public work of no aesthetic value had enormous practical significance. The Arsenal of Venice comprised eight acres of waterfront filled with lumberyards, docks, shipyards, workshops, and warehouses, where twenty-four war galleys could be built or repaired at one time.

While Venice wielded a naval power that kings envied, inland Milan put on a convincing demonstration of a city’s ground-force prowess. At the head of a “Lombard League,” the Milanese had the effrontery to face up to their lord, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and to give his German army a good beating at the Battle of Legnano, assuring their city’s freedom. By that date (1176) Venice, once a dependency of Greek Constantinople, was as sovereign as pope or emperor. For all intents and purposes, so was Genoa, so was Pisa, so were Florence, Piacenza, Siena, and many other Italian cities. Dominated by wealthy merchants, and frequently embroiled in civil strife ranging from family feuding to class warfare, the Italian cities launched a movement that the cities of the northwest sought to follow.

The essence of the new movement was the “commune,” a sworn association of all the businessmen of a town. In Italy, where the nobility lived in towns, many nobles had gone into business, and some of them helped found communes. But the commune, even in Italy, was a burgher organization; in northwest Europe nobles, along with the clergy, were specifically excluded. Cloth merchants, hay merchants, helmet makers, wine sellers—all the merchants and craftsmen of a town—joined together to defend their rights against their secular and ecclesiastical lords. Enlightened princes like Thibaut the Great and Louis VII favored communes as beneficial to town development and therefore to princely revenues. A tithe from a busy merchant was better than every possession of a starving serf. Nevertheless, the communes came in for considerable disapproval, mostly from clerical critics who saw in them a threat to the social order—which indeed they were. A cardinal

2

accused the communes of abetting heresy, of declaring war on the clergy, and of encouraging skepticism. An abbot

2

wrote bitterly: “Commune! New and detestable name! By it people are freed from all bondage in return for a simple annual tax payment; they are not condemned for infraction of the laws except to a legally determined fine, and they no longer submit to the other charges levied on serfs.”

Mere settlement in a town automatically provided escape from such feudal duties as bringing in the lord’s harvest, repairing his castle, presenting him with sheep’s dung. By the annual tax payment to which the abbot alluded, town people won freedom from a variety of other payments.

Bishops, living cheek-by-jowl with burghers, and seeing these once-servile fellows growing saucy, often had materialistic as well as ideological reasons for disapproving. At Reims the king of France recognized the commune formed by the burghers living inside the old Roman

cité

. Burghers living outside the

cité

, on the bishop’s land, also joined. The bishop objected strenuously because he wanted to keep collecting feudal dues. Eventually he had to yield, in return for an annual money payment from his burghers. Bishops and abbots did not scruple any more than secular lords to employ dungeon and rack in their quarrels with their subjects, and they usually could count on the support of the Pope. In strong language Innocent II commanded the king of France to suppress “the guilty association of the people of Reims, which they call a commune.” Innocent III excommunicated the burghers of Saint-Omer for their conflict with the local abbey.

In Troyes conflict between burgher and church did not develop, probably because by the twelfth century the counts of Champagne had completely eroded the bishop’s authority, as the history of the local coinage attests. In Carolingian times the bishop of Troyes had minted coins. In the early twelfth century the monogram of Count Thibaut—T

EBO

—appeared on one face of the coins of Troyes, the bishop’s inscription in the name of St. Peter (B

EATUS

P

ETRUS

) on the other. On the coins of the later twelfth century the name of Thibaut’s successor, Henry the Generous, appeared alone.

Pope and bishops notwithstanding, the commune swept western Europe. Even villages formed communes, buying their collective freedoms from old feudal charges. Usually the freedoms they received were written down in “charters,” which were carefully guarded. Louis VII and other progressive rulers founded “new cities”—with such names as Villeneuve, Villanova, Neustadt—and accorded them charters of freedom to attract settlers. The charter of the town of Lorris, in the Loire Valley, became a model for a hundred other towns of France, while that of Breteuil, in Normandy, became the model for many in England. In Flanders, as early as the eleventh century, towns copied the charter of Saint-Omer. “Charter” joined “commune” as a fighting word to reactionaries.

Interestingly, Troyes and its sister Champagne Fair cities were late in getting charters. This was because of, rather than in spite of, the progressive views of the counts of Champagne. The counts’ zeal in protecting and promoting the fairs undercut much of the need for a commune. The businessmen of Troyes enjoyed advantages beyond those that other towns obtained by charter. Nevertheless, in 1230, Troyes received a charter, which was afterward accorded to several other Champagne towns that did not already possess their own.

The sovereign who granted Troyes its charter was Thibaut IV, whose talent as a poet won him the dashing sobriquet of

Thibaut le Chansonnier

(“Songwriter”). Even before he inherited the kingdom of Navarre (after which he signed himself Thibaut, king of Navarre and Champagne), his territories were extensive, though held from seven different lords—the king of France, the emperor of Germany, the archbishops of Sens and Reims, the bishops of Paris and Langres, and the duke of Burgundy. For administrative purposes, the complex territory of Champagne was divided into twenty-seven castellanies, each of which included several barons and a number of knights who owed military service—altogether more than two thousand. (There were also a few hundred knights in Champagne who owed military service to somebody else.)

Throughout the territory Thibaut profited from high justice—the fines and forfeits for major crimes not involving clergy—and a number of imposts, varying from place to place, such as the monopoly of flour mills and baking ovens or fees from noble widows seeking permission to remarry. But far more important were his revenues from the towns, especially Troyes and Provins. Some years after Thibaut’s death in 1253 a catalogue of the count’s properties and prerogatives was drawn up by committees of citizens (

prud’ hommes

) from the towns: the

Extenta terre comitatus Campanie et Brie

. A few citations from the section on Troyes give an illuminating insight into the nature of the count’s revenues:

The Count has the market of St.-Jean…estimated to be worth 1,000 pounds (livres), besides the fiefs of the holders of the market, worth 13 pounds.

He also has the markets of St.-Rémi, called the Cold Fair…estimated to be worth 700 pounds…

The Count also has the house of the German merchants in the Rue de Pons…worth 400 pounds a year, deducting expenses…

The Count also has the stalls of the butchers in the Rue du Temple and the Rue Moyenne…paid half on the day of St.-Rémi, and half on the day of the Purfication of the Blessed Virgin. The Count also has jurisdiction in cases arising in regard to the stalls of the butchers.

He also has the hall of the cordwainers…

The Count and Nicolas of Bar-le-Duc have undivided shares in a house back of the dwelling of the provost, which contains 18 rooms, large and small…rented for 125 shillings, of which half goes to the said Nicolas…

The Count and the said Nicolas have undivided shares in seventeen stalls for sale of bread and fish…now rented for 18 pounds and 18 shillings.

He has the halls of Châlons…worth 25 s. in St.-Jean and 25 s. in St.-Rémi…

The fact that Thibaut the Songwriter was chronically in debt and at one point even had to mortgage Troyes merely underlines a truth about princes: the more money they have, the more they spend. Whatever his foibles, Thibaut carried on his family’s tradition of supporting the fairs. During his reign revenues achieved record heights.

While the Hot Fair (St.-Jean) or the Cold Fair (St.-Rémi) was on, Troyes was one of the biggest and certainly one of the richest cities in Europe. In the off-seasons its population decreased, but remained at a very respectable level. Its permanent population

3

was about ten thousand, a figure exceeded by only a handful of cities in northern Europe: Paris with (about) 50,000; Ghent, 40,000; London, Lille, and Rouen, 25,000. Among many northern European cities of about Troyes’ size were Saint-Omer, Strasbourg, Cologne, and York. In populous southern Europe the largest cities were Venice, 100,000; Genoa and Milan, 50,000 to 100,000; Bologna and Palermo, 50,000; Florence, Naples, Marseille, and Toulouse, 25,000. Barcelona, Seville, Montpellier, and many Italian cities were about the size of Troyes.

To pursue demography a little further, it should be noted that the population of western Europe in the mid-thirteenth century was only about sixty million. The pattern of distribution was radically different from that of later times. France, including royal domain and feudal principalities, but excluding eastern areas that became French later on, accounted for more than a third of the total, probably some twenty-two million. Germany, which included much of modern France and Poland, had perhaps twelve million people. Italy had about ten million, Spain and Portugal seven million. The Low Countries supported about four million, as did England and Wales; Ireland had less than a million, Scotland and Switzerland no more than half a million each.

These figures, though far below those produced by the Industrial Revolution, represented an enormous upsurge from Roman and Dark Age times. Practically all the increase was in northwest Europe. There the future lay.

In 1250, when our narrative takes place, Louis IX, St.-Louis, was king of the broad and disparate realm of France. The royal domain, where the king made laws and collected taxes, comprised about a quarter of the whole country; the remainder was parceled out among a score of princes and prelates and hundreds of minor lords and barons, whose relationships with each other were hopelessly intricate. Scientific-minded Frederick II, “the Wonder of the World,” was in the last year of his reign as Holy Roman emperor and king of Sicily. Henry III occupied the throne of England, enjoying an uneventful reign, though the loss of the old Plantagenet lands in France had left him less wealthy and powerful than his predecessors. Innocent IV wore the papal tiara in a Rome which had recovered a little of the prestige of its pagan days. In Spain the Moors were hard-pressed by the Christian kingdoms, while on the opposite side of Europe the Mongols, having lately taken over Russia, were raiding Hungary and Bohemia.

For much of Europe 1250 was a relatively peaceful time. As such, it may not have suited the fierce barons of the countryside, but it was congenial to the city burghers whose lives and activities constituted the real history of the period.

Troyes: 1250

A Bar, à Provins, ou à Troies

Ne peut estre, riches ne soies

.

[

At Bar, at Provins or at Troyes

You can’t help getting rich

.]

—

CHRÉTIEN DE TROYES

(

Guillaume d’Angleterre

)

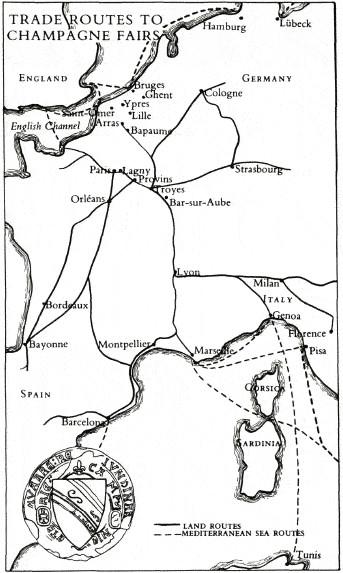

I

n the first week of July, dust clouds rise along the roads that crisscross the broad plain of Champagne. From every direction—Paris and the west, Châlons and the north, Verdun and the northeast, Dijon and the southeast, Auxerre and Sens, and the south—long trains of pack animals plod to their common destination—the Hot Fair of Troyes.