Life in a Medieval City (8 page)

Read Life in a Medieval City Online

Authors: Frances Gies,Joseph Gies

Tags: #General, #Juvenile literature, #Castles, #Troyes (France), #Europe, #History, #France, #Troyes, #Courts and Courtiers, #Civilization, #Medieval, #Cities and Towns, #Travel

An old superstition holds that when twins are born the mother has had intercourse with two different men. In a popular romance,

Galeran

, the wife of a knight insults one of her husband’s vassals by telling him that everyone knows twins are the product of two fathers. Two years later the lady has cause to repent her words when she herself gives birth to twin girls. Michael Scot, astrologer to Frederick II, asserts that multiple births are entirely normal and may run as high as seven: three boys, three girls, and the “middle cell”—a hermaphrodite.

Contemporary scientists agree that for a month each planet exerts its influence over the development of the child in the womb. Saturn bestows the virtue of discerning and reasoning, Jupiter magnanimity, Mars animosity and irascibility, the sun the power of learning, and so forth. When the influence of the stars is too strong, the child talks early, has discretion beyond his age, and dies young. Some say that if the hour of conception is known, the entire life of the child can be predicted. Michael Scot urges every woman to note the exact moment, to facilitate astrological forecasting. When his patron Frederick II married a third wife, sister of Henry III of England, he delayed consummation until the morning after the wedding, the moment astrology deemed favorable. Afterwards Frederick handed over his wife to the care of Saracen eunuchs and assured her that she was pregnant with a son, which information he also conveyed in a letter to the English king. Frederick’s confidence was justified. The next year a son was born.

It is widely believed that the sex of a child can be foretold and even influenced. A drop of the mother’s milk or blood may be dropped into pure spring water; if it sinks, the child will be a boy, if it floats, a girl. Or if a pregnant woman, asked to hold out her hand, extends the right, the child will be a boy; if the left, a girl. A woman who wants to have a boy is supposed to sleep on her right side.

When labor is imminent, the lying-in chamber is prepared for visiting and display—the best coverlets, fresh rushes on the floor, chairs and cushions. A cupboard exhibits the family’s finest possessions—gold and silver cups, enamelware, ivory, richly bound books. Dishes of sugared almonds and candied fruits are set out for the guests.

Doctors do not attend women in childbirth. Men are excluded from the lying-in chamber. Midwives are therefore indispensable, so much so that when Louis IX decided to take his queen along on a Crusade, he also took a midwife, who assisted at two royal childbirths in the Orient.

During labor the midwife rubs her patient’s belly with ointment to ease her travail and bring it to a quicker conclusion. She encourages the patient with comforting words. If the labor is difficult, sympathetic magic is invoked. The patient’s hair is loosened and all the pins are removed. Servants open all the doors, drawers, and cupboards in the house and untie all the knots. Jasper is a gemstone credited with childbirth-assisting powers, as well as the powers of preventing conception, checking menstrual flow, and reducing sexual desire. The dried blood of a crane and its right foot are also useful in labor, and one authority recommends water in which a murderer has washed his hands. In extreme cases there are incantations of magical words, whispered in the patient’s ear, but priests frown on this practice.

When the baby is born, the midwife ties the umbilical cord and cuts it at four fingers’ length. She washes the baby and rubs him all over with salt, then gently cleanses his palate and gums with honey, to give him an appetite. She dries him with fine linen and wraps him so tightly in swaddling bands that he is almost completely immobilized and looks not unlike a little corpse in a winding sheet.

He is shown to his father and the rest of the family, then placed in the wooden cradle next to his mother’s bed, in a dark corner where the light cannot injure his eyes. A servant rocks him, so that the fumes from the hot, moist humors of his body will mount to his brain and make him sleep. He remains securely bundled until he is old enough to sit up, lest his tender limbs be twisted out of shape. He is nursed, bathed, and changed every three hours, and rubbed with rose oil.

Well-to-do women rarely nurse their own children. The wet nurse is chosen with care, for all manner of qualities may be imbibed with her milk. She must be of good character, have no physical defects, and be neither too fat nor too thin. Above all, she must be healthy, for corrupt milk is blamed for many of the maladies that afflict infants. She must watch her diet—eat white bread, good meat, rice, lettuce, almonds and hazelnuts, and drink good wine. She must rest and sleep well and use moderation in bathing and in working. If her milk fails, she eats peas and beans and gruel boiled in milk. She avoids onions, garlic, vinegar and highly seasoned foods. If the doctor prescribes medicine for the baby, it is administered to the nurse. As the baby grows bigger, she will chew his meat for him. She is often the recipient of presents to sweeten her disposition and milk.

The baby is usually baptized the day he is born. Covered with a robe of silk and gold cloth, the little bundle is borne to church by one of his female relatives, while another holds the train of his mantle. The midwife carries the christening bonnet. Nurse, relatives, godparents, and friends follow. If the child is a boy, two godfathers and a godmother are chosen; if a girl, two godmothers and one godfather. The temptation to enlist as many important people as possible in the child’s behalf led to naming so many godparents that the Church has now restricted the allotment to three, who are expected to give handsome presents.

The church door is decorated for the occasion, fresh straw spread on the floor, and the baptismal font covered with velvet and linen. The baby is undressed on a silk-cushioned table. The priest traces the sign of the cross on his forehead with holy oil, reciting the baptismal service. The godfather lifts him to the basin, and the priest plunges him into the water. The nurse dries and swaddles him, and the midwife ties on the christening cap to protect the holy oil on his forehead.

Birth records

1

are purely private—records kept by the parish, are three hundred years in the future. In a well-to-do family the father may write the baby’s name and birth date in the Book of Hours, the family prayer book. If it is ever necessary to establish age or family origin in a court of law, the oral testimony of the midwife, godparents, and priest will be taken down and recorded by a notary.

When the mother recovers from her confinement, she is “churched.” Until this ceremony has taken place she is considered impure and may not make bread, serve food, or have contact with holy water. If a mother is churched on Friday, she will become barren. A day when a wedding has taken place in the church also threatens bad luck.

On an appropriate day for the ceremony the mother puts on her wedding gown and, accompanied by family and friends, enters the church carrying a lighted candle. The priest meets her at the door, makes the sign of the cross, sprinkles her with holy water, and recites a psalm. Holding one end of his stole, she follows him into the nave, while he says, “Enter the temple of God, adore the Son of the holy Virgin Mary, who has given you the blessing of motherhood.” If a mother dies in childbirth, this same ceremony takes place, with the midwife or a friend acting as proxy.

Leaving the church, the mother keeps her eyes straight in front of her, for if she sees someone known for his evil character, or with a defect, the baby will be similarly afflicted. But if her glance lights on a little boy, it is a happy omen—her next child will be a boy.

The celebration is topped off with a feast for godparents, relatives, and friends.

From swaddling bands, the infant graduates directly to adult dress. He is subject to fairly strict discipline, often physical, but is indulged in games and play. His mother may hide and watch while he searches for her, then, just as he begins to cry, leap out and hug him. If he bumps himself on a bench, she beats the bench until the child feels avenged.

Children play with tops, horseshoes, and marbles. They stagger about on stilts. Girls have dolls of baked clay or wood. Adults and children alike engage in outdoor games such as prisoner’s base, bowling, blindman’s buff. Sports are popular too—swimming, wrestling, and early forms of football and tennis; the latter is played without a racket but with a covering for the hand. All classes enjoy cock fighting. In winter, people tie on their feet skates made of horses’ shinbones, and propel themselves on the ice with a pole shod with iron. Boys joust with the pole as they shoot past each other.

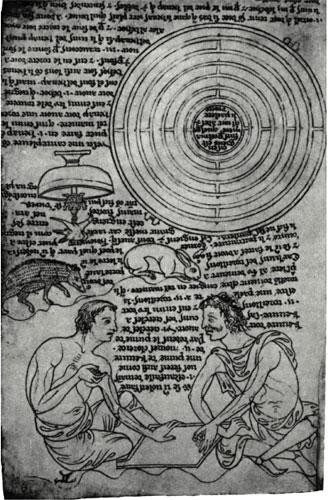

Dice players

, from the notebook of thirteenth-century engineer Villard de Honnecourt. Dice, chess, and checkers were favorite recreations of the Middle Ages.

Young and old play dice, chess, and checkers. Chess is in great vogue. Some people own magnificent boards, mounted on trestles, with heavy pieces carved out of ivory—the bishop with his mitre, the knight fighting a dragon, king and queen in ceremonial robes and crowns. The game has recently evolved into its permanent form; until the twelfth century the two principal pieces on either side were two kings, or a king and his minister, who followed him step by step. But the minister was turned into a “dame” without at first changing his obedient course of play. Then the dame became queen and was left free to maneuver in all directions.

The Church condemns games of all forms—parlor games, playacting, dancing, cards, dice, and even physical sports, particularly at the universities. Games flourish, nevertheless, even at the court of pious St.-Louis, as the Troyen knight-chronicler Joinville observes. On shipboard during his Crusade, the king, in mourning for his brother Robert of Artois, lost his temper when he found his other brother, the count of Anjou, playing backgammon with Gautier de Nemours. The king seized dice and boards and flung them into the sea, scolding his brother for gambling at such a moment. “My lord Gautier,” observes Joinville, “came off best, for he tipped all the money on the table into his lap.”

Parlor games are played, too, such as those described in Adam de la Halle’s

Jeu de Robin et de Marion

. In “St.-Cosme” one player represents the saint and the others bring him offerings, which they must present without laughing. Whoever falls victim to his grimaces must pay a forfeit, and become St.-Cosme himself. In another game, “The King Who Does Not Lie,” a king or queen chosen by lot and crowned with straw asks questions of each player, being required in return to answer a question from each. The questions and replies of the peasant characters in

Robin

are ingenuous: “Tell me, Gautier, were you ever jealous?” “Yes, sire, the other day when a dog scratched at my sweetheart’s door; I thought it was a man.” “Tell us, Huart, what do you like to eat most?” “Sire, a good rump of pork, heavy and fat, with a strong sauce of garlic and nuts.”

There is no children’s literature in the sense of stories written solely for children. But folk tales, passed down through the centuries in many versions, are the greatest single source of popular entertainment for adults and children alike. One that cannot fail to delight is the story of the shepherd and the king’s daughter:

Once there was a king who always told the truth, and who was angry when he heard the people at his court going about calling each other liars. One day he said that no one was to say, “You’re a liar,” anymore, and to set the example, if anyone heard him say, “You’re a liar,” he would give him the hand of his daughter.

A young shepherd decided to try his luck. One night after supper, as he sometimes liked to do, the king came to the kitchen and listened to the songs and tales of the servants. When his turn came, the shepherd began this story: “I used to be an apprentice at my father’s mill, and I carried the flour on an ass. One day I loaded him too heavily, and he broke right in two.”

“Poor creature,” the king said.

“So I cut a hazelnut stick from a tree, and I joined the two pieces of the donkey and stuck the piece of wood from front to rear to hold it together. The donkey set out again and carried the flour to my clients. What do you think of that, sire?”

“That’s a pretty tall tale,” the king said. “But continue.”

“The next morning I was surprised to see that the stick had grown, and there were leaves, and even hazelnuts on it, and the branches went on growing and grew until they reached the sky. I climbed up the hazelnut tree, and I climbed and I climbed and pretty soon I reached the moon.”

“That’s pretty steep, but go on.”

“There were some old women winnowing oats. When I wanted to go back to earth, the donkey had gone off with the hazelnut tree, so I had to tie the oat beards together to make a rope to go back down.”

“That’s very steep,” the king said. “But go on.”

“Unluckily my rope was short, so that I fell on a cliff so hard that my head was driven into the stone up to my shoulders. I tried to get loose, but my body got separated from my head, which was still stuck in the stone. I ran to the miller and got an iron bar to get it out.”