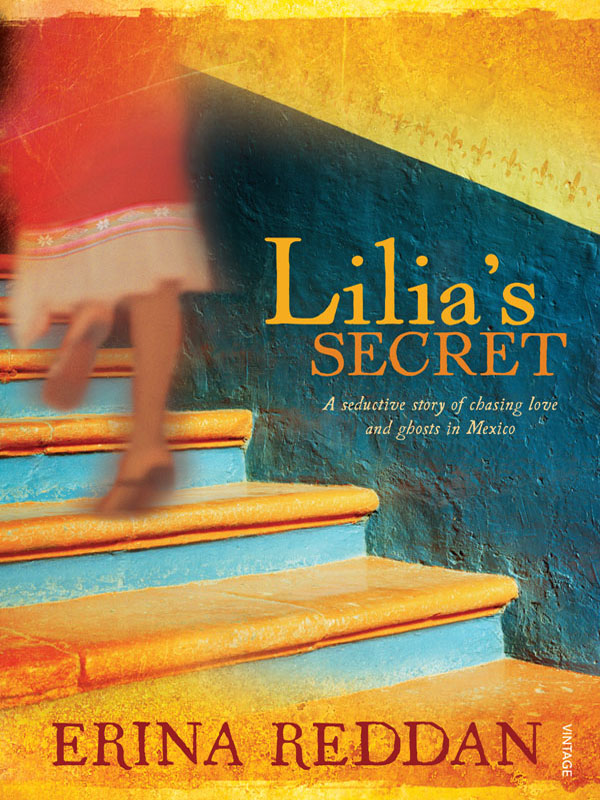

Lilia's Secret

Authors: Erina Reddan

Young and successful, Australian Maddy Maquire has fallen in love with a Mexican.

She thinks he's going to save her from her despair â until he wants her to have their baby. She can't have a child; she knows families are dangerous. On the other side of the world, Bostonian Bill Bixton's got it all â money, power, friends in high places. After he throws the retirement party of the decade, he realises what he's been missing all along: the ability to truly love.

Maddy and Bill's fates converge deep in the heart of Mexico, in search of the truth about a woman who has irrevocably changed both their destinies: Lilia de Las Flores â heroine or murderer? But when they leave behind their lives of ordered logic for the sultry, closed town of Aguasecas, they find that ghostly shadows and suspicious locals make the truth hard to uncover.

To Victor â porque te amaba antes de conocerte,

te amaba antes de que yo naciera.

I sucked the ocean air into me in sharp stabs as I leapt over jutting rocks. I loved this blue-sky, blue-water run along the cliffs with a fierceness that can only come from growing up with dry yellow paddocks.

Suddenly I could feel it. Someone else's breath coming over the top of mine, threatening to become mine. I accelerated. Not this time. Not now. The crunch of heavy steps filled my ears. I flung my arms up, scrabbling at the air, trying to block out the sound, the sensation of the rope in my hand, slapping against my thigh. I could imagine the cool of the night on my skin. That's when I stopped running.

I vomited, supporting myself with one hand against a boulder.

âAre you all right?' a man's voice broke through, but I waved him away.

âFine,' I gasped. âFine.'

He jogged backwards slowly, monitoring me, and I smiled wanly in his direction. As soon as I felt him turn the bend I slammed my fist into the rock.

I wasn't going to get to Bronte today, so I stepped off the path and climbed up a little way to the grassy top of the cliff,

where I sat and stretched my arms, trying to regulate my breathing. The murmur of the steady waves below brought me slowly back into my body.

This thing happened to me now and then. Everybody had something weird in their lives. My sister Ellen regurgitates food. She didn't realise that nobody else did it until the day her boyfriend asked her what she was chewing on.

âLamb,' she answered.

âWhat, from lunch?' he asked, and she nodded.

âBut that was hours ago â¦' He was appalled.

I hadn't told anybody about my weird thing. It hadn't happened for years.

The sun brightened and the running path was starting to pick up traffic. I preferred to run before there were too many others to dodge. I didn't want to face them now either. I slid down, and shut my eyes to find my centre. But all I could see was my mother.

She was standing at the sink, an apron wrapped around her distended belly, her lips line-thin as she rattled the dishes about in two determined inches of water. My father opened the kitchen door beside her and leant against it while shucking off his heavy gumboots. Leaving them to topple over in the doorway, he padded into the kitchen in thick woollen socks.

âThe toilet pan needs emptying,' she said without looking up. âIt's overflowing again.'

âSorry, love,' he said.

âDon't you “love” me,' she exploded. âJust empty the damned

thing.' She hurled a teacup onto the lino behind her, smashing its cream shell into shards.

I scrambled back against the wall under the kitchen table where I was shelling peas on a sheet of newspaper. Dad padded back towards the laundry door, hoisted his boots back on and quietly closed the door behind him.

Our house was like a scratch in the middle of nothing. Bone-parched paddocks stretched as far as the eye could see. The nothingness stayed the same, while the elements took turns at battering us.

On Sunday afternoons the winter wind moaned through the cracks in the weatherboard walls, while we huddled around the fireplace in the lounge, the only place of warmth in the house. Before school Helen and I would race from our beds to the fireplace in the hope that a faint ember from the night before might give out some heat if coaxed.

Every night all seven of us kids were put into four inches of water in the bathtub in consecutive pairs. As the youngest I would be last, along with Helen, the sister closest to me. We shivered, making soap bubbles between our thumb and forefinger.

In summer the heat was blister-fierce and it frayed my mother's temper. She hung heavy blankets over the windows to keep the sun from boiling us. At the end of a day of pulling in hay bales, Ben, my fair and freckled brother, shivered from sunstroke. He would recline in the kitchen, the coolest part of the house, and in a bed made by pushing two chairs together,

we treated him with juicy red slices of tomato and cold tea bags, which left traces of red and black on his skin.

Once, when I was five, it was my turn to sit beside him with the plate of tea bags and tomatoes. I laid the first rows along his arms and on his face and sat back to wait for them to take the heat. I couldn't tear my eyes away from the white patches of his closed eyelids. My big, burly brother was reduced to these two pools of fragility. I had to sit on my hands to stop myself from trying to pop his soft eyeball mounds. He moaned a low, long cow-in-pain sound and I quickly replaced the layer of tea bags and tomato. After I finished the new layer I wiped my tears away.

My family was a soup made of good, simple names: Ellen, Ben, Susan, John, Catherine, and Helen. Mine was the only one tinged with something else: Maddy, short for the French Madeline. On Saturdays my father sat in the kitchen with his hat tipped over his face, reciting our names. All the other chairs were up on the table, but the one he sat on remained on the ground, tranquil, as my mother washed the floor around him.

âWhy do you say our names over and over, Dad?'

âSo I can remember you all!' he said from under the hat. Being five years old I believed him.

He was an average man, not tall, not small, not fat. His hair was going what he called âsnowy'. It was thinning too. He always wore a checked shirt and kept up his trousers with a piece of hay twine.

At sixteen Ellen was the eldest and she played with me. She was Auntie Rock and I did whatever she asked. She told me to sit in a corner for an hour and I did. That's what I did for love. She was the only one I had a connection with. To the others I was part of the backdrop; part of the colour and movement, without definition. That's what it's like in a big family â you pick one or two to align with or against, and let the others become part of the background.

Helen and I came at the tail-end of the family with barely a year between us. We both had bowl haircuts. She had freckles and red hair; I had dark, stringy hair that hung together in clumps. You would think that we would be close, being so near in age and sharing the same bedroom. But she was Dad's âlittle shadow', always one step behind him in the cowshed or the paddock. I was indoors making a bed or sweeping a floor, trying to wipe the hard pain from my mother's face.

It was tough for my mother. Seven children, an outdoor pan toilet, goats chewing on our hand-me-down clothes on the washing line, less food than she'd like to have on the table and a house the wind whistled through.

She insisted on buying electric blankets, despite Dad's protests that we should be hardy enough to stand the cold. But she'd saved by getting the cheapest cuts of lamb and she was determined to use the money how she liked. I didn't know that then. There was just a miracle of heat waiting in bed for me one night and each night after that, and besides, that's only a small thing when I think about everything else.

In 1955 my mother twirled her fingers though her hair and laughed up into the face of the man she loved. Robert laughed back and stooped down to put his hand into the small of her back. She shivered. But he married somebody else.

In retaliation she married my father, Jack â Robert's best friend. âI'll make you love me,' my father swore. He died a disappointed man. If they had cobbled any good together it had leached away by the time I arrived.

At first it may have been a relief when it finally happened.

My mother disappeared.

One day she was banging her wooden brush on the bench trying to hurry us to the school bus, the next day she wasn't there. That day was the first time I'd ever had to do my own hair. I stood in front of the great round mirror of my mother's dresser with its scalloped shell edges, twisting this way and that to see if I'd got all the hair into the ponytail. My arms got sore and I kept having to give up and start again. When I was finally satisfied that the thick green ribbon matching my school uniform was tied, I grabbed my school bag and raced for the door. As I reached the waiting gaggle of my sisters and brothers I slowed right down, smiling and tossing my head. Nobody noticed.

It took me three days to ask whether Mum was dead.

âShe's just gone on a holiday,' Ellen said, her hands shiny and slippery as she did the dishes.

âWhere?'

âIt's a secret,' she said.

âFrom everybody?'

âYep.'

âYou know,' I accused her.

âNope.' She kept her eyes in the sink. My tea towel was soaking but I didn't change it for a dry one.

âI'll beat you,' said Susan, my sister with the long red plaits. âI'll finish the knives and forks before you finish the plates and cups.'

I kept the same pace.

That's why Susan didn't pay me much attention. I never heeded her jollying. I'd overheard her calling me âpig-headed' once.

Ellen and Susan exchanged a look.

âI'm not a kid.' I stamped my foot. âWhere is she?'

âWe. Don't. Know.' Susan stressed each word. A red flush started up on her chest. Her eyes watered. She threw the tea towel on the floor, burst into tears and ran out of the house, slamming the door with such violence that the kitchen walls shuddered.

What happened next is a bit fuzzy. This is how I remember it: Ellen hurled the sudsy plate she was washing against the far wall. As it whizzed in front of my face some of the suds flew into my eyes. I hunched over, screaming that she'd blinded me, and then I felt a huge blow to my face, or my hands really, which were cradling my supposedly injured eye. My beloved Ellen had hurt me. I fell to the ground, sobbing. I heard the door slam as someone went after Susan and I sat on the floor crying as loudly as I could.

Suddenly there was silence around me. I opened my eyes to see my father's grey patterned slippers through the spaces between my fingers. I stopped crying and looked up. His eyes were glassy and tears wet his cheeks.

The silence went on and on. In the deadest voice I've ever heard, he spoke. âYour mother's gone.'

I stopped breathing.

âShe's gone off with Robert.' He put his face in his hands and crumpled to the floor. He was down at my level, blubbering. I scuttled away, conceding the territory.