Lillian Alling (6 page)

In the 1920s, the most efficient way to travel from town to town along the coast of Brit- ish Columbia was by ship. Three or four boats called in every week at Stewart, which sits right at the head of the Portland Canal, the 70-mile-long (115-kilometre) fjord that forms part of the US/Canada boundary in the north. The line runs right up the centre of the canal; everything on the east side is in Canada and that on the west side is in the US. A tourism booklet from 1928 says that those travelling the 700 miles (1,100 kilometres) between Vancouver and Stewart will:

[S]ail through a system of enclosed waterways having no parallel elsewhere in the world, with all the comforts of a trans-Atlantic liner. Canadian National and Union Steamship Companies' steamers are noted for their comfort and safety and make the round trip in six days.

1

It was probably on one of these ships that Lillian arrived in Stewart at the beginning of June 1928 on her second attempt to get to Siberia. Travelling up the canal, she would have seen its spectacular beauty, as described by L.A.N. Potterton:

The mountains were steep-sided with ice-eroded valleys, some of which contained living glaciers. They were covered with lush green timber reaching high towards the heavy blanket of snow which covered the high peaks that gave birth to scores of milk-white streams and waterfalls.

2

When Lillian arrived by ship at the beginning of June 1928, the towns of Stewart and Hyder, BC, and Hyder, Alaska, plus the surrounding mining communities, had a total population of about a thousand people. After disembarking at Stewart, she set off along the boardwalk to walk through Hyder, BC, and into Hyder, Alaska. The date was June 6, and at the United States Customs and Immigration Office at the entrance to the American town, she met Colonel Edwin R. Stivers. He had opened an office there on March 31, 1921, and although his main job was the collection of customs duties, over the years Stivers had also taken on responsibility for immigration inspection.

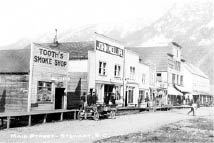

Stewart, BC, c. 1920s. University of Washington Libraries AWC2933.

The decision that the international boundary between British Columbia and Alaska should be located at the centre of Portland Canal was finalized in October 1903, although the treaty was not officially signed until May 14, 1910. However, even before that decision was made, the towns of Stewart and Hyder, Alaska, had been founded at the head of the Canal in response to the discovery of enormous mineral wealth in that area. The first lode mineral claims in the area were staked at Bitter Creek by D.J. Rainey in 1899. He also staked out forty acres on the mud flats of the Bear and Salmon rivers, which empty into the head of the canal, but as he was not sure if he was in Canada or the US, he recorded his claims in both countries. In 1903 prospectors Robert M. and John W. Stewart arrived, secured a portion of Rainey's holding and staked the townsite of Stewart at the farthest end of the canal between the mouth of the Bear River and the international boundary. (This town has the distinction of receiving the greatest average annual snowfall of any town in Canadaâ18.75 feet or 572 centimetres.) The new town gave miners access to mines on the Canadian side of the line and experienced its first boom in 1910. However, its real economic success came with the opening of the Premier Mine, 15 miles (24 kilometres) north of the town. This mine operated from 1919 to 1953, producing gold and silver ore and paying out thirty million dollars in gross earnings.

The American town of Hyder, named after Canadian mining engineer Frederick Hyder, was established 2 miles (3 kilometres) south of Stewart. It sits on a point of land between the Portland Canal and the mouth of the Salmon River, although part of the town was constructed on pilings pounded into the mud flats. (This portion of the town was destroyed by fire in 1948.) In its early days, Hyder was primarily an access point to the Riverside Mine, north of the town, where gold, silver, copper, lead and zinc were extracted between 1924 and 1950, but the town's boom years occurred between 1920 and 1930. Although a few ships called at Hyder when they had freight for the mine and some of the smaller passenger vessels from Ketchikan stopped there on a more or less regular basis, most of the passenger vessels that came up the canal were Canadian and their port of call was Stewart.

3

A third town, Hyder, BC, was established between Hyder, Alaska, and Stewart, initially as a place to accommodate a dock and a 4,000-ton bunker to store concentrate from the Premier Mine. The 12-mile-long (19-kilometre) aerial tramline that connected it to the mine was the second longest on the continent. This tiny town, which also provided accommodation and entertainment for the mine workers, was built entirely on pilings driven into the mud flats, and its dozen or so buildings faced landward, their backs to the sea. They included a few hotels, a restaurant, two brothels and the offices of the Canadian Customs Service. Today nothing but a few piling stubs remain to show that Hyder, BC, ever existed.

Stivers did not allow Lillian to enter Alaska. According to the official record from the United States Department of Labor, which was in charge of immigration, Lillian Alling, a citizen of Poland, aged thirty-two, female, who had arrived in Hyder “by highway” was “debarred” from the United States because she had no visa. (The term “highway” refers to the 2-mile (3-kilometre) stretch of boardwalk between Stewart and Hyder.)

There was actually no formal entrance policy into the United States at Hyder during the years between 1920 and 1930, so it is possible that she was rejected because she was neither American nor Canadian. According to her own statement at the Canadian Customs office in Niagara Falls, though she had lived in Canada from 1915 until 1921 and had apparently worked in New York State between 1921 and 1926, she had not applied for citizenship status in either country. And if she had held a visa at any time during that period, it was obviously no longer valid.

Changes had occurred in both US and Canadian immigration and travel rules subsequent to Lillian's first entry into the United States from Canada. Although there had been a continuous undocumented movement of people back and forth between Canada and the States during the early 1920s, both countries had tightened regulations for people from Europe. In 1921 the US Quota Act had limited the number of immigrants from Europe to about 350,000 per year, and in 1924 the National Origins Act reduced that European quota to about 165,000. In addition, the United States had introduced Prohibition in 1920, and as a result border controls had gradually become tighter: the production and sale of liquor remained legal in Canada, and the US was struggling to prevent smuggling activity at the border.

However, it is quite possible that Stivers turned Lillian back at Hyder simply because she had announced that her ultimate destination was Siberia. He would know that she could not possibly reach it by travelling north by land. Hyder is situated on the Alaska Panhandle, that strip of Alaska that divides northern British Columbia from the Pacific Coast. It is a wilderness of mountains and glaciers, thousands of inlets and rivers and streams, gullies and cliffs. Even today, there are no roads and no trails. The only way to get from town to town along this coast is by boat. Walking it would be a physical impossibility. Stivers knew that once Lillian entered Hyder, she had either to stay there, go 14 miles (22.5 kilometres) north to the Riverside Mine or turn around and go back to British Columbia.

Having dealt with the British Columbia Provincial Police and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, enduring months in prison and losing an entire year on her journey, it is little wonder Lillian wanted to leave British Columbia and Canada. Thus, she must have been very unhappy to be turned away at the US border. But she had learned an important lesson in Hyder. By attempting to cross the international border there, she found out she would never get into the United States through an established boundary crossing. Any future attempt at entry from Canada would need to be clandestine.

After being refused entry into Alaska, Lillian needed to make both short-term and long-term decisions. Short-term included where to spend the night, and her obvious choice was Stewart, which was a rather rowdy town at that time. A man who had served there as the local policeman in those days said:

[T]here were three licensed hotels situated on the main street, and as soon as they opened up for business, they filled up as fast as a church rummage sale, and with the same amount of enthusiasm. The only thing different was the language that was being used.

4

The government liquor store did the most business in the town. In 1928 it “sold more liquor than any other individual liquor store in the province of British Columbia.” L.A.N. Potterton wrote:

The whore-houses perhaps came next in the line of big business, followed closely by the gambling tables. The local bank manager once told me that his best customers at the savings account level were the girls from the red-light district ⦠The whole town seemed to be involved in gambling and drinkingâeveryone was making money and spending it just as fast as they made it.

5

Lillian's long-term options were few. She could wait for a ship in Stewart that would take her north to Skagway, Alaska, and thence over the Whitehorse and Yukon Railway to Whitehorse, but having been turned down at Hyder because she had no visa, she would expect to be turned down in Skagway as well. It is also quite possible that she did not know of the railway's existence. Alternatively she could take a ship back down the coast to Prince Rupert, follow the rail line to Hazelton and begin a fresh attack on the Telegraph Trail. However, she may have been unable to afford the fare. Her third option was to make her way to Hazelton by land.

It is not possible to walk from Stewart directly to the main line of the Telegraph Trail as the terrain is too steep and dangerous. Two years before Lillian arrived in Stewart, surveyors had attempted to lay out a route from Hyder through the Bell-Irving River valley. The report of their endeavours is noteworthy:

We discovered a freshly blazed trail, and having followed it, we met a party of Indians camped on Bell-Irving River. These Indians, Gunanoot and party, have trapped in this country regularly for a number of years and know it thoroughly ⦠they told me they did not think it feasible to build a trail up the west bank of the Bell-Irving because as one approaches the Telegraph Line, the country is subject to very bad snow slides ⦠my intention was to go up the west bank of the Bell-Irving to the Salmon [Teigen] Creek, cross that stream, stay a night at the shelter cabin on the Telegraph Line at this point and then return along the east bank of the Bell-Irving. But when we arrived at the junction of the Salmon [Teigen] and Bell-Irving about a mile from the Telegraph Line, the rain was falling in torrents and the river was extremely high, consequently ⦠we had to return as we had come, by the west bank. However, I found that the information given me by the Indians was amply verified. For 5 miles below the junction of the Salmon [Teigen] and Bell-Irving the snow slides run clear from the top of the mountains into the river and at times block it up; consequently it would be impossible to maintain a trail here.

6

Although overland passage to the Telegraph Trail was unavailable, it is likely that Lillian learned that the Cranberry Trailâa trading route used by the Gitxsan First Nations peopleâwas the best route back to Hazelton and the Telegraph Trail. The Cranberry Trail network begins with a 12-mile (19-kilometre) hike up into the canyon of the Bear River and from there through the Bear Pass to Meziadin Lake. The next part of the trail follows the Nass River and then the Cranberry River to the head of Steven's Lake. The final stretch lies alongside the Kispiox River then through the Kispiox valley to Hazelton.

By the summer of 1928, Lillian had been travelling for a year and a half and had walked thousands of miles. But a good portion of that time had been spent in jail or within the confines of the city of Vancouver. Presumeably she was well rested, but probably also out of shape since her last attempt to walk the Telegraph Trail. Now her strength and endurance in the wild would be freshly tested. Most of the journey ahead of her would have been considered a moderate to difficult hike.

7

Through the mountainous sections the terrain was rugged, to be sure, but in the river valleys the trails flattened out, and in the month of June they would have been dry as well. If she walked an average of 30 miles (48 kilometres) a day, it would take her about two weeks to make the journey from Hyder to Hazelton.