Little Kids, Big City: Tales from a Real House in New York City (With Lessons on Life and Love for Your Own Concrete Jungle) (12 page)

Authors: Alex McCord,Simon van Kempen

Sometimes I really wish we had family living near us. Although we schedule regular chats via video with our more technologically advanced relatives, the others miss the day-to-day little things like Johan singing “Hit the Road, Jack,” or an art project the boys created together. It’s also impossible to get Grandma over to babysit if Mom and Dad need to go out for 45 minutes. To that end, we’ve made our own family, whether it’s with childless friends who want to borrow some for an afternoon, or friends who have kids of similar ages and want to get them together for drop-off playdates. When it’s just for an afternoon, four kids can be easier to watch than two, as they have a ball playing and the novelty of being together is fresh.

TOP 10 THINGS CAREGIVERS HAVE INADVERTENTLY DONE TO AMUSE, ANNOY OR THRILL US:10. Put cheese away in the freezer while talking to the boys.9. Accidentally used a household cleaning wipe when changing a diaper. Johan did not notice.8. Let baby François lick the edge of a shot glass of vanilla rum on vacation He wanted more and tried to grab the bottle!7. Get into our backyard blow up pool fully clothed because she didn’t have a swimsuit6. Obsessively boil every dish baby Johan used and made François put on gloves when holding him4. Offered to take the boys out for dinner and asked them where they wanted to go (First mistake.) Our enterprising young men directed him to an upscale French bistro and ordered $60 worth of pasta and hot chocolate. Yes we paid him back.3. Spent hours helping the boys make homemadeglitter-filled photo collages for Simon

s and my birthdays—we still have them!

2. Really “get” the working-from-home model, and help enforce it in kid friendly terms1. When a former caregiver told several neighbor hood parents and nannies that we were awful people unprompted her replacement loyally told everyone the truth and to consider the source

Chapter 7

“Putting To Death Is Not Nice,” a Duet for Two Boys and a Guitar

Lessons Learned by Boisterous Children

Alex

It cracks me up when people expect children to be perfectly well behaved all the time. Quite honestly, why should they be? We adults aren’t. Many adults treat each other horribly on a regular basis, and I would rather have a boisterous boy running around me with a drippy paintbrush, than a superior kid sitting still and saying nasty things about her frenemy. In many ways kids are feral animals, and at the end of each day if there’s no blood and no ruined furniture,

we’ve won.

About four months ago we came home one weekend afternoon to find the boys madly playing their guitars and running around. Our friend and their honorary godfather, Sava, was on the sofa howling with laughter and we eagerly asked him what had happened. Sava said, “François, come and sing your song for Mommy and Daddy.” Both boys happily launched into a song that basically involved screaming, “Putting to death is not nice, killing isn’t good!” over and over while rocking out with their guitars and throwing their heads around. I’m still not sure what inspired the song, although Sava did confirm that nothing had been put to death, but I fully agree that in any case it is not nice. They’ve begun protesting the death penalty early.

The boys understand the basics—i.e., no killing. No breaking things, no punching in the face (unless your brother really, really annoys you). When you get to the finer points of appropriate behavior it’s frustrating to not be able to make yourself understood. We went through a big learning curve when the boys were between two and three years old. Once they are able to communicate with you using words, it’s tough to not open the flood-gates and bombard them with information, but we had to stop ourselves because it just wasn’t sinking in. Though I’m a very verbal person to begin with, it’s unbelievably annoying to explain why pouring mustard sauce in the toaster will break it, why dropping Daddy’s best watch would mean that Daddy could never wear it again, why there’s no eating yogurt on the suede sofa despite their promise to be very careful and on and on. Although they could speak and understand, at that age they still couldn’t communicate anything approaching an adult level, and we finally learned to save our breath, or at least put it on pause for a few years. We admitted that training kids was rather like training animals—reward for good behavior and physically prevent the bad behavior. I still do try a short explanation each time, but if it doesn’t work I move on to the next option.

What works best for us 90 percent of the time is a three count, followed by a time-out if the behavior hasn’t stopped. For example, if François is holding a coloring book over his head and not giving it to Johan, he has a three count to give it back, otherwise it’s a time-out. When an action is destructive or dangerous, we skip the counting and go directly to a time-out: if Johan hits François, it’s an automatic timeout and vice versa. A third permutation is when there’s a behavior that has to stop immediately, say if Johan has a big blue indelible marker and is running through a white hotel suite. I swoop in and grab the marker as to risk a three count would be to risk decoration of the sofa. Neither of us is above scaring the daylights out of either of them with a well-placed growl or shout, and yes, when necessary we have spanked them both and will again.

Sometimes I get angry that people mock our perceived lack of discipline of our children on the show, when in reality on the streets of Brooklyn with no cameras around, we’re a hell of a lot stricter than most parents. We’ve discovered that when dealing with the boys on the show it’s just not possible to please everyone. If we are too strict there will always be someone to be critical and if we’re not, then another set call us overly permissive. It’s definitely a case of damned if you do and damned if you don’t! Yes, we do sometimes want to set our hair on fire and yes, the boys can be rowdy. We also high-five each other when we pick up the kids and the grown-up delivering them goes on about how well-behaved and mature they were. We take the good with the bad. No one is perfect—everyone is interesting.

Our goal is to raise children who are intelligent and productive. We want them to be inquisitive, confident, have empathy for others and a strong moral compass. It’s useful for them to know the social graces, such as not to chew with their mouths open, not to be boorish or eat or drink to excess and to have a firm handshake. I don’t particularly care whether they are considered “nice” or “popular,” although those qualities are good, too. Ultimately if my boys are gain-fully employed and happy, that’s all that matters. I want to see them excited by life and all it has to offer, not passively sitting by so that they won’t offend anyone. I want to raise my children more or less in the way our parents raised us.

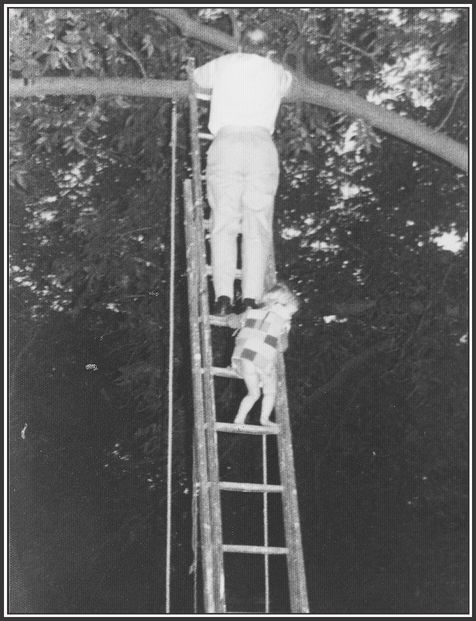

One of my first memories of being wrangled as a kid was at our vacation home in St. Thomas—this would have been in the late ’70s. Our house was on a cliff and was sort of donut-shaped with a pool in the middle, and on that afternoon a fabulous poolside cocktail party was in force. Amidst the jollity, my three teenaged brothers decided a fabulous addition to the festivities would be to put on a show for the guests by diving off the roof of the house into the pool. Dad or someone took a great photo of my brother Paul standing on the roof, arms spread wide, ready to plunge. Someone else chuckled and said, “Don’t break your neck.” Meanwhile I was determined to steal the food from and pull the tail of the long-suffering German Shepherd who belonged to our next-door neighbors. For some reason I always thought he should eat apples with me, instead of his dog food, and was prepared to enforce the issue. “Croix, if she annoys you just bite her,” someone said to the dog. He never did, patient dog that he was, but I got the point. They say that girls play “let’s have a tea party” and boys play “let’s jump off the roof.” There’s a photo of me somewhere playing “let’s have a tea party

on

the roof,” so between Simon and me we have passed on rather boisterous genes to our children.

on

the roof,” so between Simon and me we have passed on rather boisterous genes to our children.

Alex and Dad on Ladder

Simon

I am a great believer in letting one’s children learn the hard way. And while it’s always good to learn from others’ mistakes, we all have our own to learn from, too.

One night when I was around 11 years old my mum was out and I was in bed. I am sure my brother, six years my senior, was around, but my memory of this night doesn’t recall. What I do recall though, is as clear as if I had just watched it on video. I crawled out of bed and put my clothes on over my pajamas and left the house, walking out onto the street. At the time we were living on the outskirts of a small town in Australia with cane fields bordering our back fence. Our street was lined with houses but backed by farms. It was semi-rural and also a dead-end, as the bridge had been washed out years ago and was never repaired. As such, it was a pretty safe area and this was 1975. Anyway I picked up my golf club and as I wandered down the street, I saw my first cane toad of the night. This particular toad had been introduced into Australia in the ’30s to eradicate the cane beetle, which was damaging cane crops, however it was less successful at that than it was as multiplying at an alarming rate. As a result, I had only ever known it as a pest and vermin. No different to how an NYC kid regards rats.

These toads secret a poison (stored behind their eye in the parotid gland) as part of their defense against predators and my 11-year-old brain understood that this poison, if it got in my eyes, could cause blindness. As I raised my golf club back over my head and swung it forcefully forward, the toad took a slight step. Instead of catching its body dead center and sending it 100 yards down the bitumen road, I caught its face, causing its parotid glands to rupture and spray my face with their contents.

Scared and petrified, I raced home, madly rinsed my eyes with water and as I crawled back up to my top bunk, I remember glancing at the ceiling and thinking that that would be the last thing my eyes would ever see.

Sometime throughout the next afternoon I suddenly remembered that I was

supposed

to be blind and was elated to know that I clearly wasn’t. But what this experience did teach me was that if I was meant to be somewhere, then there I would be. There was no more sneaking out of the house after that.

supposed

to be blind and was elated to know that I clearly wasn’t. But what this experience did teach me was that if I was meant to be somewhere, then there I would be. There was no more sneaking out of the house after that.

Other books

Fierce Salon Episode 1: A New Adult Smexy Serial by Aspen Drake

Wicked Destiny by Tiffany Stevens

Fade Back (A Stepbrother Romance Novella) by Brother, Stephanie

Frost Hollow Hall by Emma Carroll

The World as I Found It by Bruce Duffy

The Hotel on the Roof of the World by Alec le Sueur

Broken Pieces (Riverdale #2) by Janine Infante Bosco

Between a Rockstar and a Hard Place by MacIntosh, Portia

Enoch Primordial (Chronicles of the Nephilim) by Brian Godawa

Her Dakota Man (Book 1 - Dakota Hearts) by Mondello, Lisa