London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City (26 page)

Read London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City Online

Authors: Drew D. Gray

they pick up `bits and pieces' of work and are paid so little that they have to rely on supplements and charity. [The residuum] is economically dead. It maybe possible to galvanize it into a temporary appearance of life, to raise up a social monster that will be the terror of the community; but the best that can be really hoped for is that it should gradually wear itself away, or in the coming generations be reabsorbed into the industrial life on which it is at present a mere parasite.97

C. S. Loch shared Helen's opinion that the `residuum' was beyond redemption while believing that the rest of the working class could be improved by raising individual standards.9R

Beatrice Webb believed that co-operation, trade unionism and state supplements might be used to help workers lift themselves out of poverty, while accepting that there were distinctions to be drawn between those who were out of work as a result of economic circumstances and those who were deemed idle and shiftless. Beatrice was aware that `the industrial organization, which had yielded rent, interest, and profits on a stupendous scale, had failed to provide decent livelihood and tolerable conditions for the majority of the inhabitants of Great Britain"' Fabians argued that it was society, through the infrastructure of the State, which had the power to redress the problems caused by market economics. Ultimately socialists had little time for philanthropy, seeing it as `an aspect of wealth and privilege that should abolished'*' loo Home visits could be seen as intrusive and as a continuation of middle-class attempts to control the behaviour of the working classes for their own ends rather than simply an act of selfless giving.

As a result, Helen Bosanquet has suffered from being characterized as representing old-Victorian values of self-help but it is more appropriate to see her as someone struggling with the huge social problems she saw everyday in her COS work. Reconciling the need to support those in need without reducing them to a life of dependency was uppermost in her mind. She was a realist and her views bear closer inspection because she asks difficult questions that resonate today. In writing that `many of our attempts to "elevate the masses" are only attempts to train them to our own standard, not because it is intrinsically better, but because it is what we are used to and can understand' she challenged the prevailing wisdom that the middle classes necessarily knew best.'°' She went on to warn her readers that: `We need to be quite sure that we really want to cure poverty, to do away with it root and branch. Unless we are working with a whole-hearted and genuine desire towards this end we shall get little satisfaction from our efforts'. In what might be regarded as a critique of middle-class philanthropy she added that `in the absence of poverty the rich would have no one upon whom to exercise their faculty of

For all this Bosanquet was optimistic that the solutions for society's social problems lay in the institution of the family; at a time when some socialists were convinced that the family could not possibly survive the ravages of capitalism. Bosanquet had faith in the East End matriarch, even if she had little in their menfolk. `Among a certain low type of men the prevailing expression is one of vacuity, of absence of purpose or character; among the women corresponding to them the prevailing expression is that of patient endurance, she opined.113 She rejected Fabian socialism and opposed the provision of school meals as undermining the family and as a 'subsidy to lazy parents; not as a benefit to poor incomes.'04

In 1909 the two camps came crashing together in the Poor Law Commission Report where they differed in their findings. Bosanquet, who authored the major report, defended the role of private charities while in the minor report Webb championed the cause of bureaucratic socialism as the way forward for welfare policy."' McBriar sets out the distinction neatly: `The COS believed that economic independence for all was desirable, and that this could achieved by a "wise administration" of charity and the Poor Law; Socialists, on the contrary, aimed at an economic dependence on the State which would [in the view of the Bosanquets] be degrading to the working class and to the whole community.1107 In a recent volume Kathleen Martin has warned against seeing such a clear distinction between the two camps, suggesting that the Webbs had strong reservations about the value of social Writing in 1896, C. S. Loch, secretary of the COS, set out the default position of the organization: `To shift the responsibility of maintenance from the individual to the State is to sterilize the productive power of the community as a whole and also to impose on the State ... so heavy a liability ... as may greatly hamper, if not also ruin it. It is also to demoralize the individual""

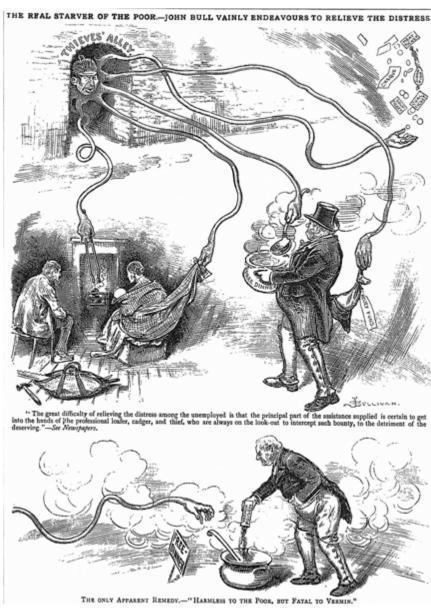

Figure 6 `The real starver of the poor. - John Bull vainly endeavors to relieve the distress', Fun, November, 1887. In this cartoon Fun illustrates the problems of providing benefits to poorer families, suggesting that the criminal `residuum' as well as those deserving of help would exploit this.105

Clearly we are still struggling to address this conundrum in our modern society. The provision of state benefits is sometimes accused of creating a'dependency culture' and tabloid newspapers delight in printing occasional stories of `greedy benefit scroungers' who abuse the welfare system at the expense of the `honest' majority. Neither of these women were revolutionaries although both would have described themselves as feminists; both believed that women had a more important role to play in society than Victorian society was prepared to allow them. Neither of them saw the birth of the welfare state in 1945 although both lived long enough to see the creation of old age pensions in 1908: this must have been viewed with satisfaction in both camps. Indeed the move towards state interference or intervention, whichever way it is characterized politically, was well underway as the new century dawned. In 1900 Britain spent approximately £8.4 million on poor relief, the only form of `social security' funded from taxation. On the eve of the First World War this had leapt to £43.3 million and now included unemployment and health insurance, pensions and social housing schemes."'

`BLOODY SUNDAY' AND THE EVENTS OF NOVEMBER 1887

Having considered the contrasting attitudes towards solving the social problems of the day, as expressed by two leading female philanthropists, we can now return to the more serious expressions of discontent that so unnerved contemporaries. The spring of 1886 had brought protestors to the centre of London, with riotous consequences as we have seen: the following hot summer had led to scenes of hardly less horror from a middle-class perspective as large numbers of unkempt Londoners lounged about and undertook their ablutions in the fountains of Trafalgar Square. Later in 1887 the situation became markedly worse and the venue was, once again, Trafalgar Square.

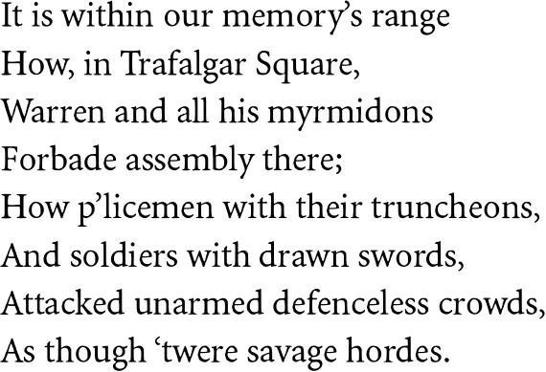

The year 1887 marked Queen Victoria's fiftieth year on the throne but not everyone was content to join in the festivities. As the homeless gathered in Trafalgar Square the socialist agitation that had led to the previous year's riots resurfaced, as a large banner was unfurled with the legend `We will have work or bread"" Local residents complained: `It is impossible for any large meeting to be held without its being attended by a considerable number of roughs and thieves whose only object is to promote disorder for their own As autumn approached, the police, now under the stewardship of Sir Charles Warren, who favoured a militaristic no-nonsense approach to policing, decided to clear the square of its temporary occupants. Meetings were broken up with force and, faced with regular demonstrations of the unemployed and Irish Home Rule agitators, Warren took the decision to ban all meetings in the square. Warren's action provoked a storm of protest at the restriction of freedom of speech and assembly."' Reynolds's Newspaper asked `Are we in London or St. Petersburg?' in a direct comparison between tsarist Russia and Liberal England. 114 The Metropolitan Radical Federation called a meeting in the square to protest the imprisonment of an Irish MP. On 13 November marchers converged on the square from all over the capital and this time the police had taken note of the committee of 1886s report and had stationed mounted officers `at every angle of the square' with ranks of policemen positioned on all sides."' Warren had no intention of allowing the marchers to hold their rally and a police baton charge surged into the ranks of the protestors. A desperate battle ensued and while the supporting cavalry from the Life Guards were not required the police caused some 200 casualties among the protesters and two or three men were killed. The debacle even became the subject of a popular song as the story of `Bloody Sunday' unfolded.

In reality the soldiers, with or without drawn swords, were not involved in the fracas. The press reacted with a mixture of admiration for the police efforts and condemnation of their rough-hand tactics. In this they reflected the character of the newspapers and their editors. The Pall Mall Gazette led with the headline, `At the point of a bayonet' before describing the police as `ruffians in uniform'. Although the military were not called upon, the Pall Mall Gazette reported that they had been issued with live rounds and were ready to ride the protesters down `beneath the hoofs of the chargers of the Life Guards'. The writer reminded the reader of the carnage that had occurred at a Reform rally in Manchester in 1819 and suggested that, save for the `marvelous forbearance and good temper of the crowd' the `Peterloo massacre' could have been repeated in Trafalgar Square."' The Daily Chronicle, by contrast, praised the self-control of the police but blamed the authorities for letting the demonstration happen in the first place. The Times were quick to support the police and Warren in particular for `his complete and effectual vindication of that law which is the sole bulwark of public liberty'. The Standard attacked the `selfish and cruel demagogues who bring together these ignorant crowds to serve their own ambitious purposes, and the Daily Telegraph was similarly quick to point the finger at rabble rousers `carrying red flags and thick sticks""

Most seemed to accept that things could have been a lot worse; two policemen were stabbed and several heads broken but initially it was not thought that fatalities had occurred. In fact one person, Alfred Linnell, did collapse after the disturbances and died in hospital 12 days later. His funeral was occasioned by some protest at the actions of the police: `Remember Linnell's martydom!' urged the closing line of Halliwell and Lewis' popular song. Linnell was a law writer, a minor member of the bourgeoisie, not a creature from the abyss. In an incident reminiscent of recent public demonstrations, Linnell was supposedly injured when a mounted police officer attempted to move a small crowd."' The coroner found for the police - there were no visible hoof marks on the deceased ,only small bruises by the left knee [that] should not have caused his death'. 121 The truth was hardly as important as the symbolism of Linnell's death. William Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette would use `Bloody Sunday' as a stick to beat the chief commissioner with: Warren's militarization of the police would come back to haunt him, and eventually lose him his job. His final denouement would be in South Africa, at Spion Kop, the scene of one of the British army's heaviest defeats in the nineteenth century.