London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City (39 page)

Read London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City Online

Authors: Drew D. Gray

Attempts to create a uniform system of police in London in the wake of the chaos of the Gordon Riots were scuppered by the intransigence of the City of London in 1785, which was not prepared to give up control over its own policing networks - with some justification as they appear to have operated quite effectively.' In 1792, in response to concerns about the avarice of entrepreneurial JPs in Middlesex, seven police offices were established in the capital, with a small force of thief-takers attached to each. This reform was inspired by the example of Bow Street where Sir John Fielding had been developing a system of detection and patrols with some tacit support from government. However, when Peel eventually submitted his proposals for a professional body of policemen any detective element was notably absent. Once again this reflected the attitudes of Englishmen towards policing: detection was considered to be little more than a system of espionage. Thus, the `new' police were distinguished not only by their blue swallow-tailed coats and stove-pipe hats, but also by their role. They were there to patrol the streets and by doing so prevent crime and maintain order. They were not thief-takers like their colleagues at Bow Street and it took some time for this situation to change.

The role of the new police brought them into immediate conflict with the working classes of nineteenth-century London. One way of conceptualizing the Victorian police has been to view them as `domestic missionaries'; as tools of a puritanical middle class bent on dragging the degenerate proletariat up to their standards of decency and morality. This standpoint, which sits in stark contrast to early histories that depicted the police as much needed companions in the war on crime, places the police at the centre of a class war raging across the nineteenth century.5 That the Victorian police acted as a 'lever of urban discipline' (as Robert Storch has characterized it) is evident in the sorts of activities they performed:' patrolling the streets, moving-on traders and dice players and arresting drunks and prostitutes. Policing was concentrated on the poorer, working-class districts of London, in the belief that controlling working-class behaviour would prevent crime in the wealthier areas of the capital: `policing St. Giles to protect St. James' as it was sometimes called (St Giles was a notoriously poor and criminal area situated where Tottenham Court Road meets Oxford Street in the modern capital). This brought them into direct contact, and indeed conflict, with the inhabitants of working-class districts and those using the streets. Costermongers, or `costers' (street traders who sold their wares from barrows), were particularly vexed at being told to `move along' as they tried to eek out a living. Given that the police also broke up the recreational activities of costers - such as illegal dogfights - it is not surprising that punching a policeman (to the cry of `Give it to the copper!') was a popular pastime. `To serve out a policeman is the bravest act by which a costermonger may distinguish himself', one proud costermonger told Henry Mayhew.'

However, partial views such as Storch's can obfuscate the reality of the situation on the ground and Stephen Inwood's work on the early experiences of the Metropolitan Police has offered a more balanced view of police practice. Inwood demonstrated that while directives were circulated to the police that were aimed at curbing some expressions of working-class culture it is less clear that they were rigorously applied.' At an operational level the police appreciated that imposing notions of middle-class morality on working-class districts was fraught with difficulties. In order to police an area effectively the police knew they had to work with the community. If the actions of individual or collective policing alienated the broad mass of working people they would be unable to police by consent. The Met simply did not have enough officers or enough power to be `domestic missionaries' in the way that this role has been envisaged by Storch.9 As a result a `softly softly' approach to policing working-class areas developed and the police achieved a level of toleration and respect among the policed communities. Working people were also quick to utilize the police courts, and the police themselves, to help resolve their disputes and prosecute those that offended, assaulted or robbed them, as Jennifer Davis' work on the police courts has shown.lo

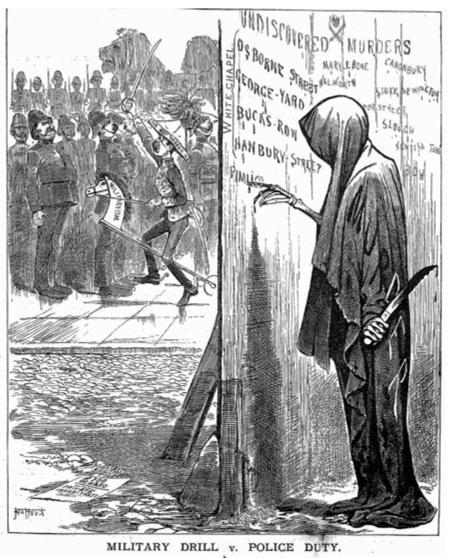

Thus, by the last quarter of the nineteenth century the police in London had at least overcome some of the incipient problems that had dogged their early development as a 'new engine power and authority' on the streets of the capital of Empire." Despite this the Pall Mall Gazette's attack was not entirely unfounded. The police, or at least those that ran the police - Warren and Home Secretary Henderson - were easy targets for press condemnation, as the Ripper apparently killed and mutilated at will. The Gazette was not alone in suggesting that the police had got their priorities all wrong, as Figure 8 demonstrates. The Gazette complained that:

Battalion drill avails nothing when the work to be done is the tracking down of a midnight assassin, and the qualities which are admirable enough in holding a position or dispersing a riot are worse than useless when the work to be done demands secrecy, cunning, and endless resource."

`Battalion drill' referred to Warren's apparent preference for seeing his men in uniform and on parade rather than in plainclothes skulking about the streets. This brings us back to the second issue that beset the embryonic police force in the nineteenth century: the apparent absence of detection.

Figure 8 `Military drill v. police duty, Funny Folks, September 1888.13

As we have seen the early commissioners of the Met shunned the notion of detection as un-English and unwelcome and so the new police followed the model of the old watch and not the Bow Street Runners. However, in 1842 the police came under intense pressure to catch the murderer of a woman whose dismembered body was found at a house on Putney Heath, Roehampton. The killer was quickly identified as Daniel Good but it took over a week to finally entrap the killer, who was found almost by accident by a former policeman working for the railways.14 The garroting panic of 1862 further demonstrated the need for professional thief-takers adept at taking on what were seen as professional thieves emanating from the newly conceptualized `criminal class' The Detective Department was established in the wake of the Good murder enquiry and over the second half of the century the negative perception of detection was slowly eroded. The public began to warm to the idea of the detective as characters in popular fiction, such as Dickens' Inspector Bucket in Bleak House (based on the real-life Detective Inspector Field), helped to glamorize the role. Bucket was followed by Sergeant Cuff, in Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone, before Sherlock Holmes firmly established the detective in the public psyche in the 1880s. The short stories of Conan Doyle demonstrated the value of detection in the capture of criminals and the solving of crime. The CID, created in 1878, was fully established by the time of the Whitechapel murders, claiming 15,000 arrests each year in London and by 1884 there were 294 police detectives on the Metropolitan force.

FENIAN DYNAMITARDS: THE METROPOLITAN POLICE AND EARLY IRISH REPUBLICAN TERRORISM IN LONDON

Britain remained reluctant to create a political secret police such as existed in several Continental states, but increasingly pressures began to force moves in that direction. As a result of revolutionary politics in Europe, Britain had become home to political refugees such as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. While the press in England boasted that `it would never happen here' the prospect of revolution and the growing fear that Britain's dominant position in the world was being undermined by foreign competition prompted a limited surveillance of radicals, anarchists, nihilists and socialists, some of whom were to be found among the new immigrant communities of the East End. Even the British Library was approached for a reader's ticket so that certain individuals, such as Marx and his daughter, could be watched. The threat to the Empire did not, however, come from the author of Das Kapital or from the black-coated bomb-throwing anarchists satirized by G. K. Chesterton in The Man who was Thursday. Britain's threat lay much closer to home in the unresolved and ongoing political time bomb that was Ireland and Irish nationalism.

In December 1884 James Gilbert Cunningham, newly arrived from New York City, took lodgings in Great Prescott Street. He had passed through customs with almost 60 lb. of American-made dynamite. Soon afterwards Henry Burton, taking a similar route as a steerage passenger, also arrived in East London and found digs at 5 Mitre Square, just inside the City and one of the sites of the Whitechapel murders. Unfortunately for Burton, one of the other residents at number 5 was a City policeman, Constable Wilson. Burton and Cunningham were Irish-Americans fully committed to the cause of Irish nationalism. They had come to bring terror to the heart of the Empire by attacking a number of high-profile locations, including the Houses of Parliament.'5

Burton's role was to co-ordinate the bombings. The first of these, planned for 2 January, was on the underground railway. Joseph Hammond was the guard on the 8.57 train to Hammersmith that left Aldgate at 9.01 p.m., four minutes late. As it passed the signal outside of Gower Street station on the Metropolitan Line at 9.14 p.m. there was a'very loud explosion at the fore part of the train, which `smashed the windows and put out all the lights." When it came into Gower Street a porter ordered all the passengers off so that the train could be examined for damage. PC Crawford, who was on duty outside Gower Street, heard the explosion and saw a 'flash and a cloud of dust' and hurried down to see what had happened. There he took names and addresses and calmed a screaming woman who had sustained a nosebleed. None of the injuries seemed that serious.

The newspapers carried reports of the `outrage' in their morning editions; the Pall Mall Gazette secured the eyewitness testimony of one of the passengers, a Mr William Smith of Euston Road. Smith told the paper that:

We had passed King's-cross without anything unusual happening, and were chatting quietly together when we were terrified by a fearful crash like thunder, accompanied by an immense sheet of flame, which seemed to lick the sides of the carriages, and for a moment it seemed as if the tunnel was on fire. To add to the terror of the situation both our lamps went out and we were left in total darkness. Several of the passengers cried out that they were hurt, and some women who were in the next compartment screamed loudly.

He went on to add that `the force of the concussion threw us all off our seats, and umbrellas, hats and papers were mixed up in terrible confusion' 17 The explosion also unseated the ticket collector, and was felt above ground by pedestrians, `while the horses of the omnibuses and other vehicles were so startled by the noise that they were restrained only with great difficulty from running away"' The police arrived and, with the help of Colonel Majende, the Home Office's inspector of explosives, examined the damage. The bomb had done relatively little damage to persons or property. While it had taken out the windows in the carriages and created a small hole in the tunnel wall it had singularly failed to halt the running of the underground for any significant period, nor had it, thankfully, taken any lives or caused serious injury.

Its more immediate effect was to remind English society that a small and desperate band of Irish republicans were determined to take violent direct action in support of their cause. There had been attacks in 1884 at Victoria Station and a number of other London terminals and three `dynamitards' had blown themselves up in an attack on London Bridge. The blast was not intended to destroy the bridge, but to frighten the government. Sir Edward Jenkinson (assistant under secretary for police and crime in Ireland, and in charge of secret service operations there) then received reliable information that the Houses of Parliament were next on the terrorists' list of targets.19 In May 1884, Robert Levy and his brother were in Trafalgar Square when they noticed a black bag unattended `lying under one of the lions ... facing the National Gallery' Being naturally curious they examined it. Finding it locked, Robert gave it a kick before his sibling picked it up. This brought it to the attention of the policeman on duty in the square, who took the bag and the boys back to Scotland Yard. There the bag was opened and found to contain explosives: 171/2 cakes wrapped separately in papers on which was printed `Atlas powder A' to be precise.20 The bag also contained detonators and fuses.

While the attack on Trafalgar Square had been foiled by the inquisitiveness of two teenage boys and the rather crude nature of the explosive device, three other bombs had exploded in London that May. One took out the windows at the rear of the Junior Carlton Club injuring five people, while a second exploded outside the home of Sir William Watkin Wynn on St James' Square. The most audacious attack, however, was on the offices of the recently created Special Irish Branch at Scotland Yard.21 At 9.20 a.m. on 30 May an explosion damaged the buildings at the police headquarters injuring several people and knocking one officer unconscious. The `enemies of civilisation have been busy this year [ 1884]', warned one regional newspaper, and they were clearly resuming the `Dynamite War' in 1885.22