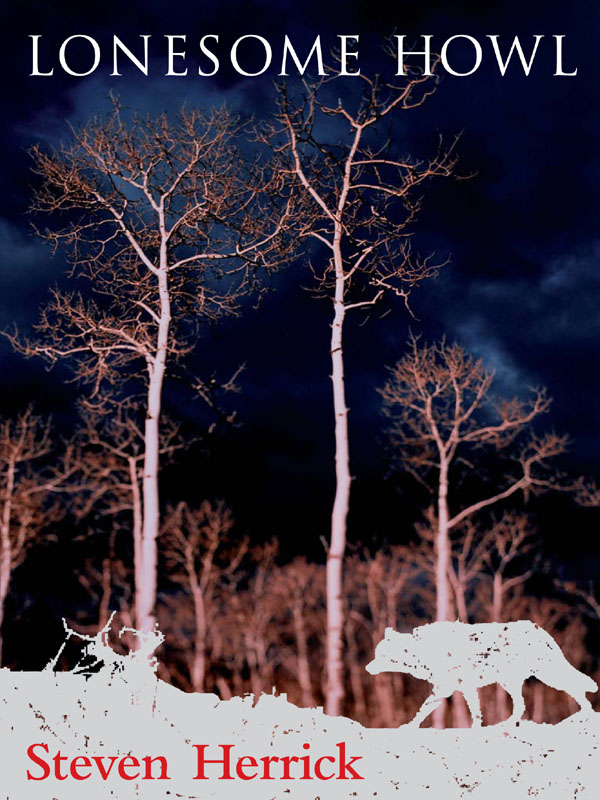

Lonesome Howl

STEVEN HERRICK was born in Brisbane, the youngest of seven children. At school, his favourite subject was soccer, and he dreamed of football glory while he worked at various jobs, including fruit picking. Now, he's a full time writer and performs in many schools each year. He loves talking to students and their teachers about stories, poetry, soccer and even golf.

Steven lives in the Blue Mountains with his wife and sons. Visit his website at

www.acay.com.au/~sherrick

Love, ghosts & nose hair

â shortlisted in the 1997 CBCA awards and the NSW Premier's Literary Awards

A place like this

â shortlisted in the 1999 CBCA awards and the NSW Premier's Literary Awards, and commended in the 1998 Victorian Premier's Literary Awards

The simple gift

â shortlisted in the 2001 CBCA awards and the NSW Premier's Literary Awards

By the river

â Honour Book in the 2005 CBCA awards and winner of the Ethel Turner Prize in the NSW Premier's Literary Awards

LONESOME

HOWL

Steven Herrick

First published in 2006

Copyright © Steven Herrick 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander St

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Herrick, Steven, 1958 .

Lonesome howl

ISBN 9 781741 14656 1.

ISBN 1 74114 656 9.

1. Teenagers â Juvenile fiction. 2. Father and child â Juvenile fiction.

3. Self-actualizatioin (Psychology) in adolescence â Juvenile fiction.

4. Wolves â Juvenile fiction. I. Title.

A823.3

Cover photograph from Photolibrary/Brad Green

Cover design by Sandra Nobes

Set in 10.5pt Apollo by Midland Typesetters

Printed in Australia by McPherson's Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Teachers' notes are available from

www.allenandunwin.com

When I was eighteen, I told Mum I wanted to be a writer. The next day, she went out and bought me a desk and a chair from a second-hand furniture store. Nearly thirty years on, I still write my books at that desk.

Mum died last year.

I like writing at her desk. It brings us closer.

With love.

S.H.

Also by STEVEN HERRICK

Water Bombs

Love, ghosts & nose hair

A place like this

The simple gift

By the river

for children

The place where the planes take off

My life, my love, my lasagne

Poetry, to the rescue

The spangled drongo

Love poems and leg-spinners

Tom Jones saves the world

Do-wrong Ron

Naked Bunyip Dancing

CONTENTS

Lucy

My name's Lucy Harding.

Lucy's not short for anything,

it's just Lucy.

That's right, with a ây'.

Only people from the city

spell it with an âi',

or call themselves Lucienne.

I'm not French,

and I'm not from the city.

I'm from Battle Farm.

My grandma named it that,

on account of her always saying,

âIt's a battle to keep this place;

a battle to survive.'

And she did pretty good.

At surviving, I mean.

She died a few years ago,

aged ninety-two.

She's buried up the hill

next to Grandpa,

overlooking their farm

and I reckon she's up there

thinking,

Why did my daughter marry

someone like him?

Mr Right.

He's never right. He just thinks he is.

He

is Dad,

but I don't want to talk about him.

Swampland

There are two farms in this valley.

No one else can be bothered

cutting through the ragged paperbarks,

the Paterson's curse

and the creeping lantana.

Wolli Creek flows deep into the valley

through a sandy swamp,

alive with mosquitoes and bugs.

From the banks, big granite boulders

step up to the hills.

Nothing for farming.

Everyone at school says

we live in the arse-end of the earth.

They all tell stories about

diseased feral animals prowling,

quicksand that swallows you whole

and strange lights hovering above the bog.

Sometimes, when I'm bored, I join in.

I tell the little kids

about long-winged bats

and wild pigs, big as lions,

and blood-curdling screams at midnight.

It's all I can do to stop from laughing,

but, hell,

it passes the time.

The Hardings

So there's me.

I'm sixteen.

And my mum,

who milks our cow, Martha,

and cooks what she grows,

scraping dirt off potatoes and carrots,

washing them in the sink.

Every evening after dinner

she sits on the back verandah

looking up at her parents' graves.

She doesn't say much

and that suits me fine.

And there's Peter, my brother,

who's twelve, but acts like he's eight.

You know, always pestering me,

or playing shoot-'em-up games on his PlayStation.

Once, he climbed up on the shed roof

in his Superman cape.

Yeah, no kidding.

I bet you're thinking

he jumped off and broke his arm.

Right?

Wrong.

Superman was scared.

Mum got the ladder

and she sent me up

to help him down.

I had to talk all nice and careful,

like I was worried.

âCome on, Peter. It'll be all right.

Superman can't die.'

Dad kept fiddling with his car.

That's all he ever does.

Tinker with the engine,

shoot his rifle at targets

and go on about

everything I do wrong.

The death of poor Winnie

If Peter thinks he's Superman,

Dad acts like some

straight-shooting outlaw.

He sets himself

on the old vinyl car seat against the gum tree

and he gets Peter to draw pictures,

rabbits and deer and kangaroos,

on big sheets of paper.

Then he sticks them on the shed

and fires away.

Does he hit the target?

Well, he hits the shed, at least.

Except one time,

when he had way too much to drink.

I sat under the house

hoping he'd shoot his foot off.

Now

that

would be funny.

He blasted away

doing his best to hit the mark

but he missed everything

except Winnie, the pig.

You should have heard Superman cry.

Mum rang Mr Samuels, the town butcher,

who drove out and cut up poor Winnie.

We had pork for dinner

and bacon for breakfast,

every day for a month.

It's the only time

I can remember the old bastard

doing anything useful.

Questions

When Dad's head is so far under the bonnet

I imagine walking up behind,

giving him one swift kick

and running away,

never coming back.

But not Peter.

He tries to help.

He hangs around,

shuffling his feet in the dirt,

picking up tools,

leaning over the engine,

asking questions.

Dad only ever answers

with a grunt or a shrug.

Peter keeps talking,

jabber jabber jabber.

Dad lifts his head and frowns,

spits in the dirt

and picks up another spanner

as he's forced to listen to his own son.

If that was me doing all the talking

he'd tell me,

straightaway,

to piss off.

I lounge around,

pretending I'm reading,

listening to Peter

and knowing that my stupid father

doesn't know how to shut him up.

âKeep talking, Peter,'

I whisper to myself.

âAsk another question.

Go on.'

Lucy, and the work

Mostly I stay out of his way.

Simple as that.

At dinner I eat quicker than I should

and keep my head down.

Whenever anybody asks me

to get the cordial from the fridge

or the salt from the pantry,

I do it without a word.

Don't think I'm weak.

I'm not.

I'm snarling underneath

and they know it.

I'm doing what I'm told to avoid getting hit.

When Grandma was alive

Dad would take his dinner outside

because she stared him down.

Grandma said what she liked.

She wasn't afraid of anything.

She'd grin across the table.

âYou don't own nothing, Lucy,

unless you work for it.

Remember that.

Working is the owning.'

She'd look at Mum,

daring her to say something,

but no one crossed Grandma.

Some people die

In the last year of her life

Grandma could barely walk.

Every morning she'd struggle out to the verandah,

one arm around my shoulder,

her shaky hand holding a walking stick.

There she'd sit, watching the farm.

He'd keep out of the way,

in the shed or out the back,

smoking one fag after another.

Grandma knew what went on.

She waved her stick at him

whenever he came near.

She'd tell my mum to stand up to him,