Lords of the Sky: Fighter Pilots and Air Combat, From the Red Baron to the F-16 (26 page)

Read Lords of the Sky: Fighter Pilots and Air Combat, From the Red Baron to the F-16 Online

Authors: Dan Hampton

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Military, #Aviation, #21st Century

In any event, the veterans were dispersed widely so that they could pass along what they’d learned. This was indeed fortunate for the Luftwaffe, as September 1939 was fast approaching and the world, as it was known, was about to change forever.

H

E WHO GIVES BACK AT THE FIRST REPULSE,

AND WITHOUT STRIKING THE SECOND BLOW,

DESPAIRS OF SUCCESS, HAS NEVER BEEN, IS NOT,

AND NEVER WILL BE A HERO IN WAR, LOVE OR BUSINESS.

—

FREDERIC TUDOR

A PENETRATING, UNEARTHLY

wail instantly jarred the men awake from a sound sleep. It was the kind of sound that made teeth ache and turned the heart cold; a steadily rising scream that made skin itch and hair stand on end. Eyes wide, the soldiers rolled from their bunks and tumbled toward the doors, grabbing rifles in the predawn gloom. Some covered their ears, and some fell to the ground. Others lifted their rifles and stared at the sky, trying to see the threat—an enemy that was out of reach up beyond the mist.

All they saw was death.

As the ground erupted in explosions, a bicycle flew into the air, followed by boots and several pots. Even the braver sort of man dropped his weapon and ran for the trees or the river. The concrete blockhouses guarding the bridge disappeared, and most of those inside were vaporized in an instant. Pieces of the others were flung high into the air before thudding back to earth in bloody, charred fragments. The horrible banshee screaming gave way to roaring engines and the rushing noise of wind over metal. If anyone had been left alive, he would’ve seen the three gull-winged aircraft level off, vapor streaming from thick wing tips, then duck lower just above the trees before turning west and disappearing. It was nearly 4:45 a.m. in the morning of September 1, 1939—and the Second World War had just begun.

Twenty-year-old political bandages of Versailles fell away, exposing the festering wounds remaining from the Great War. A treaty that was both too shortsighted and too visionary had finally unraveled in a spectacularly bad manner. The Soviet Union, enormous, unpredictable, and tenacious, was determined to forge a place in the world, while Germany, bitter and proud, was fanatical about regaining its status.

Case White, the German plan for the invasion and destruction of Poland, was the first link in this chain. The pretext given was the Polish Corridor created at Versailles and its threat to Germany. Backed by President Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the corridor gave Poland “free and secure access to the sea” by cutting a large swath of territory through Germany to the Baltic port of Danzig. There were issues with this that Hitler exploited as justification for going to war. Danzig, like most of the cities along the Baltic shore, was predominantly German, with infrastructure, port facilities, and shipping industries heavily financed by German investors. Nearly two million Germans lived in the area, and the corridor also severed East Prussia from Germany itself.

Part of the solution had been a railway connecting Berlin to its eastern province. This crossed the Vistula River at Dirschau (modern Tczew) just below Danzig (modern Gdansk) and was a linchpin for any German advance into the area. Both sides knew this, and the Poles had carefully prepared the bridge for demolition in the event of a German attack. Blockhouses adjoining the bridge contained troops who would blow the structure if ordered. These blockhouses were the first, critical targets of the war and had to destroyed on time, with precision and surprise.

Enter the Stuka.

Flown in Spain with the Condor Legion, the Ju 87 was capable of highly accurate surface attacks using 250 and 50 kilogram bombs or its 20 mm cannon. The inverted gull-wing design both improved the pilot’s visibility and permitted the shorter, sturdier landing gear necessary for rough fields. The wing was also constructed in sections, allowing for easy disassembly and transport by rail to a combat operations area. In keeping with the forward operating base concept, the fuselage was constructed in large removable sections for engine maintenance. Interchangeable parts were common, as was the avoidance of welded fittings whenever possible.

The Stuka’s diving technique was unique. A more vertical dive angle made for less aiming error, so the pilot acquired the target through a window in the floor, then set a dive lever. This limited the movement of his control column and automatically popped dive brakes, which would keep the aircraft at 350 mph during the attack. Rolling in around 15,000 feet, the pilot set the dive angle at 60º, 75º, or 90º by using red lines painted on the cockpit window. He would then aim with his cannon sight at the target and release the bomb manually at a preplanned altitude.

The pilot could also initiate a sequence that began a 6 g dive recovery at 1,500 feet. This would automatically pull the aircraft back through the horizon, set the propeller for full throttle, climb, and retract the dive brakes. In those days, 6 g’s was considered excessive so the auto system saved many a Stuka crew from the barely understood g-forces of high-performance aircraft.

*

Bombing accuracy was very good, and the addition of the Jericho-Trompete dive siren was initially devastating to the defenders on the ground. It was precisely this combination of surprise, tight accuracy, and devastation that Oberleutnant Bruno Dilley delivered to the Polish defenders of the Dirschau bridge early on that Friday morning in September 1939.

In the minutes following the attack, four German army groups lunged across the borders into Poland from Pomerania, East Prussia, and Slovakia. Warsaw, though expecting such an attack, was hopeful that Britain and France would honor their pledges to defend against any German aggression. Those pledges had been made with the naive understanding that the Soviet Union, much closer and with strategic interests in mind, would also move to defend Poland should it become necessary.

What London, Paris, and Warsaw didn’t know was that Germany and the USSR had concluded a secret nonaggression pact on August 22. This gave Stalin eastern Poland all the way to the Vistula River plus Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia all in return for noninterference with any German attack, should it become necessary. And Hitler made certain that it was necessary. On August 30, a German border post near Gleiwitz was “attacked” by the Poles—or at least by men wearing Polish uniforms.

*

So Poland was on her own. Hitler had rightly calculated that France and Britain would not move fast enough to stop him, and if he could win quickly, then there was little for his adversaries to gain by a declaration of war. With the Polish Corridor absorbed back into Germany, then there was no port available to reinforce Poland, so aid could come only from the Soviet Union—and that had been dealt with.

Checkmate.

And it worked.

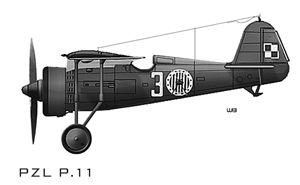

Despite the betrayal, the Poles fought back hard. Their victories in the air were visible reminders of what fighting spirit can accomplish, and they were a shock to the Luftwaffe. The Poles were flying Pzl P.7 and Pzl P.11 fighters—at one point fairly advanced but now hopelessly outclassed by the Bf 109. The Pzl P.11 was an all-metal open-cockpit monoplane with decent range and a maximum speed of 240 mph. The gull wing gave some improved visibility, good turning performance, and an easy recovery from stalls. It generally mounted two 7.92 mm machine guns, but with nonretractable landing gear, a fixed propeller, and very few radios, it was severely disadvantaged. This makes the 110 acknowledged German losses to this monument of a bygone era even more astounding. The first Polish combat loss probably occurred on September 1 at 5:30 a.m. near Krakow in southern Poland. Capt. Mieczyslaw Medwecki and his wingman Wladyslaw Gnys scrambled out of Balice and were attacked by two Stukas. Medwecki, the group commander, was immediately shot down and killed. Gnys turned on the Stukas, damaging one of them. He then found two Do 17 bombers, and German sources confirm they both came down near the village of Zurada (though not necessarily shot down by Gnys).

September 3 found the German Fourth Army advancing east from Pomerania to link up with the Third Army moving west from Prussia. Four days later Warsaw was in danger of encirclement from two enemy armies, and by September 19, 100,000 Polish troops had surrendered. Contrary to the myth that the Polish air force was destroyed on the ground, the fighters, particularly the Pursuit Brigade’s five squadrons near Warsaw, battled the Germans every day.

Fighting on to the inevitable conclusion, the Poles eventually lost more than 100 of their 130 aircraft before combat ended on October 6, 1939. However, many of the pilots escaped and, as we shall see, continued flying in France or England. As for the Germans, though they claimed a tactical victory, the campaign was a strategic defeat. The Soviet Union gained eastern Poland, including the oil basins of Lublin and Krasno, without shedding a drop of blood. More important, the Red Army was closer to Berlin and the Wehrmacht some 75 miles farther from Moscow.

The Polish campaign gave the Luftwaffe valuable lessons concerning supply, logistics, and, above all, surface attack. Five

Schlachtgruppen

had been created by Adolf Galland, adding power to the combined-arms blitzkrieg ground assault tactics. Three of these groups would be equipped with Stukas and one with Do 17 bombers. The last one, Fliegergruppe 10, became part of a test and evaluation unit dedicated to the development of new tactics. Everything learned in Poland was passed back for dissection and consideration.

Many technical innovations had been affirmed, such as radio communication, the accuracy of the dive-bomber, and the vital component of close air support. Other lessons were not so straightforward. How, for instance, had the numerically and technically inferior Poles inflicted such damage on the best air force in the world? Other scenarios were lost in the euphoria surrounding victory, but Galland wondered what would occur when they faced an enemy who fought back on even terms.

THE FACT THAT

Hitler’s next moves were against Denmark and Norway pushed this very real consideration even further to the rear. In February, Norway’s territorial waters had been used by the Royal Navy to capture the

Altmark

, a German resupply ship, and Hitler decided to take this as an excuse to implement Case Green, the invasion of Denmark. This would seal off the Baltic and give him a secure land route for desperately needed Swedish iron ore. Denmark surrendered immediately, so the Germans then drove through Oslo, Norway, and north toward Trondheim to link up with their troops at Narvik. In mid-April the British and French countered by sending some 12,000 men into Norway, but they were forced to evacuate in early May.

On May 10, 1940, following many postponements, Hitler executed Case Yellow. Only the fall of France, he reasoned, would force Britain to sue for peace. Both Paris and London had been expecting an attack, but they’d assumed it would come the previous fall, so by now the edge had been dulled somewhat. And the French felt secure: on their northern flank were twenty-one divisions of the Belgian army and a network of fortified positions along the Meuse River. To the south lay the seemingly impassable Ardennes Forest and the Maginot Line. Besides, the French army was one of the largest in the world, augmented by British Expeditionary Force ground troops and the Royal Air Force.

Initially there were nine RAF fighter squadrons on the continent, all flying Hawker Hurricanes. Accompanied by Blenheims, Lysanders, and Fairey Battles, they were part of the British Air Force (BAF) in France. This augmented the BEF Air Component, with six Hurricane squadrons, supporting Lord Gort and the army.

*

Three more fighter squadrons were attached to the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) and answered to RAF Bomber Command in England.

*

The Hurricane had been developed in response to Air Ministry specification F.7/30 during the 1930’s, when Germany began rearming and war looked likely. Sydney Camm, Hawker’s chief designer, insisted on conventional technology that could be assembled using existing jigs and tooling. The plane used a box-girder-type construction with no welds for ease of maintenance and field repairs. Wood and fabric were utilized over hollow steel tubing, which again made the Hurricane easier to service. It was found in early fights that German shells would often pass through the fabric without exploding. Powered by a 1,030-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin II engine, the fighter maxed out at around 330 mph. Initial aircraft carried eight .303 Browning machine guns and enough ammunition for fifteen seconds of continuous firing. Production began in June 1936, and when the war began there were some five hundred Hurricanes in service with eighteen RAF fighter squadrons.

By the spring of 1940 it had proven itself in combat. On October 21, 1939, a flight of six Hurricanes from 46 Squadron shot down four of nine Heinkel 115 floatplanes over the North Sea. A few days later in France, Pilot Officer “Boy” Mould from 1 Squadron sent a Dornier Do 17 spinning down in flames near Toul.