Lose the Clutter, Lose the Weight (11 page)

Read Lose the Clutter, Lose the Weight Online

Authors: Peter Walsh

Controlling a chaotic lifestyle

Controlling a chaotic lifestyle

Starting tasks and seeing them through to completion

Starting tasks and seeing them through to completion

In addition, poor impulse controlâanother symptom of ADHDâis evident in many people with hoarding disorder. In one study, nearly three-fourths of people who hoard reported that they compulsively bought stuff. In another, more than half would compulsively purchase things for sale or pick up free things.

ADHD isn't just for kids. More than half of children diagnosed with ADHD may still be dealing with the condition as adults. But adults with ADHD don't have a monopoly on lack of focus, lack of organization, and a “chaotic lifestyle.” I think

much

of the population has developed these qualities.

The Terrible Two: Anxiety and Depression

Full-fledged anxiety and depression are very common in adults. Major depression affects about 16 million American adults during any given year, and about 40 million have an anxiety disorder. Millions more have milder versions

of these problems that affect their lives but don't warrant formal diagnosis and treatment.

This increasing awareness of the links between the stuff we own and our mental landscape is something that has long fascinated me. I'm not a mental health professional, but I have noticed something compelling during my many years of working with people whose clutter has overwhelmed them: You can see people's sadness and fears in the clutter around them.

Remember that anxiety and depression are two of the most common mental health challenges in our communities today. Think about this: Anxiety is often characterized as an undue preoccupation with the future, with excessive worry about situations that might happen and the impact they could have. Depression is often characterized as a preoccupation with things past, with a concern about what might have been and the “if only's” of one's life.

Remember those two types of clutter we looked at in

Chapter 1

? There's memory clutter, which reminds you of an important person, achievement, or event from the past. I think memory clutter often gathers in the homes of people with some degree of depression. And then there's “I might need it one day” clutter, in which people hang on to stuff in anticipation of an imagined future. Among these folks, I've noticed a recurring theme of anxiety.

I find it interesting that these two kinds of clutter so closely parallel two common types of mental health problems in our society. Maybe it's possible that the stuff we own and obsess over is the physical manifestation of the mental health issues that challenge our minds.

When I have tough conversations with people about the clutter in their homes, they often tell me that their worries, their sadness, and their inattention played a major role. Again, it's never about the stuff. The focus, instead, should be on the factors that led the stuff to accumulate. Clutter develops because of your mood, your emotions, your attitudes, and your behaviorsâand each is intimately connected to the others.

And on a related note, it's not about the

fat

either. Just as you didn't say, “I'm going to deliberately bring more stuff into my home than I really need, then hang on to it longer than I should,” I'm certain you didn't say this:

I'm going to overfeed my body with more calories than it needs. I'm also going to be sure to sit around so I don't burn off too many of those calories. Eventually I'll have such a thick layer of food, alcohol, and sodas around my body that I won't be able to fit into my current clothes.

If you're overweight, that's

not

how it happened. Instead, you lifted snacks, entrées, and drinks to your mouth thousands of times. Only some of those times was your action driven by true hunger or thirst. It's quite likely that the same types of emotional upset or inattention that led to your cluttered home also played a role in the current state of your waist and hips. That's because excess weight can be associated with depression.

One study of more than 2,400 obese and overweight adults found that those with abdominal obesityâin other words, a big bellyâwere more than twice as likely to have symptoms of major depression. In another study that followed nearly 66,000 middle- aged and older women for 10 years, those who were depressed at the beginning of the project were more likely to become obese later. On the other hand, those who were obese at the beginning were more likely to become depressed later.

Anxiety also may influence people to become overweight. In a U.S. study of whites, African Americans, and Latinos, people in any of these groups who'd had an anxiety disorder in the past year were more likely to be obese. And among more than 2,100 Dutch people, those who had symptoms of depression or anxiety at the beginning of the study were more likely to be bigger around the

waist 2 years later. (Their HDL, or “good” cholesterol, also fell, which could pose a threat to heart health.)

And let's not forget the issue of inattentiveness. Whether you have ADHD or you simply don't pay attention to your food, inattentiveness may boost your odds of being overweight.

A number of studies on people seeking treatment for their obesity found that a higher percentage of them had ADHD compared to the general population. (These studies, however, weren't set up to prove that one caused the other.) In another study, researchers compared men who'd had childhood ADHD with men who

didn't

have childhood ADHD. The men who'd had ADHD were significantly more likely to be obese (about 41 percent compared to 21.6 percent in the non-ADHD group).

And women who remembered having more ADHD-like symptoms in childhoodâsuch as inattention, poor impulse control, and hyperactivityâhave been found to have a higher risk of obesity in adulthood.

I'd like to recap two main points here, since they're crucial for confrontingâand conqueringâyour clutter and your weight in this program:

1. Anxiety, depression, and ADHD may raise people's risk of hoarding and becoming overweight. Since hoarding and regular excessive clutter aren't necessarily far apart, this research very well may apply to you, dear reader, even if you don't have hoarding disorder.

2. You don't need to have a full-fledged, diagnosable case of depression, anxiety, or ADHD for this to apply to you, either. Milder relatives of these problemsârespectively, feeling blue, stressed, unfocused, or impulsiveâcan affect your purchasing and eating habits.

Knowing whether any of these issues are lurking in your mind will put you in a better position to confront them and separate them from your eating habits and your attitudes toward acquiring and hanging on to possessions.

In the next chapter, you'll put your mind to the test to see what kinds of factors may be driving your clutter and weight. Make that

several

tests!

WHERE ARE YOU ON THE CLUTTER SCALE?

WHERE ARE YOU ON THE CLUTTER SCALE?

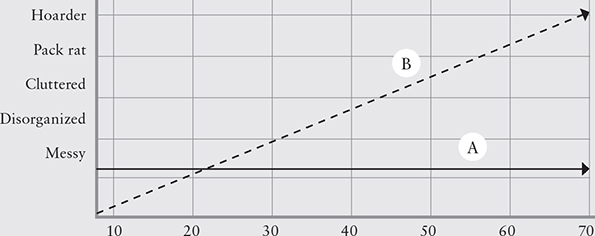

The degree to which we accumulate clutter can be thought of in terms of a sliding scale on which most of us can locate ourselves. I've found it useful to think of the different stages of the scale like this:

Each of these stages on what I call “The Clutter Scale” is marked by increasing levels of clutter, more difficulty discarding things or letting them go, more severe trouble in relationships with family and friends due to clutter, increased social isolation, and increasing mental health issues.

No single factor can predict whether a person will struggle with clutter, though many factors may come into play: genetics, family history, environment, social conditioning, and one's upbringing. Sometimes a childhood trauma associated with personal belongings can play a role.

I vividly remember a woman I worked with who found it impossible to let go of anything that came into her home. She told me that as a child, her family had moved across the country. Her parents guaranteed that she would find all of her belongings in their new home, but when they proved too expensive to move, her parents threw them away. In many ways, that grown woman was still the traumatized 8-year-old who'd been betrayed. As an adult, she made sure that no oneâincluding herselfâwould ever separate her from her things.

Some people just never learned the simple routines of maintaining a home when they were kids. Once, working with a young family, I asked why they threw their laundered clothes into the corner of their

master bedroom. The wife said this was how she was raised. She was surprisedâand a little amazedâwhen I showed her how to fold clothes and iron a shirt. She'd never before seen or done either!

Organization is a skill like any other that must be modeled and taught from an early age, or else kids are more likely to struggle with clutter later on. Many of my clients have confided that their clutter has gotten worse with age, and that an intervention when they were younger might have caught the problem before it became extreme.

Consider a small lesson contained in my Clutter Scale, which you can see once we plot the scale on a graph along with age.

It's not unusual for people to deal with some level of clutter (or messiness) their entire life. Sometimes they struggle with the same level of clutter over long stretches of their lives (represented by the A line). Others see the piles of possessions around them grow deeper over the years (as seen on the B line).

Whether you've been following the A line at any of these clutter levels for years, or you've been riding the B line into more severe problems, the program in the following pages is going to help you steer your arrow downward.