LOSING CONTROL (10 page)

Authors: Stephen D. King

This combination is potentially lethal for Western capital markets.

If the emerging world is busily buying US Treasuries, the price on Treasuries will be higher, and the yield lower, than might be the case in a ‘free market’ situation, where the only focus of fund managers is to maximize returns for a given amount of risk.

This creates problems for Western investors who, as argued above, are actively engaged in the ‘hunt for yield’.

If Treasury yields are unusually low, investors will be forced to buy something else.

What is that ‘something else’?

In the late 1990s, following the onset of the Asian crisis, the asset of choice was equities, helped along by the new technologies associated with the dot.com boom.

Seemingly, any fool capable of putting together an investment prospectus was able to raise funds, not because the business case was necessarily sound but because the funds were so freely available.

The Federal Reserve added fuel to the fire by keeping policy rates relatively low, because of the unjustified fears of global recession stemming from the Asian crisis and, later on, the concerns associated with computer failures linked to the new millennium (although why monetary policy had to play a role in the Y2K threat is, to say the least, puzzling).

The decision to keep interest rates low after the Asian crisis is understandable but, in hindsight, was based on a misinterpretation

of the effects of the crisis.

Economic models are mostly driven by real, rather than financial, flows: changes in the value of exports and imports, not changes in the value of holdings of financial assets.

Admittedly, policy rates and exchange rates play a role, but the Asian crisis filtered through the policymakers’ models only via trade.

If demand was collapsing in Asia, it followed that US and European exports to Asia would collapse, leaving the Western world facing recession.

There was no recession.

The collapse in Asia was precipitated by capital flight.

Funds that had happily nestled in Asia went back to the US and Europe.

As Asian current-account deficits diminished, so the US current-account deficit grew bigger, funded by the capital which was now fleeing Asia.

The inflows helped push down short- and long-term interest rates, lifted the US equity market and contributed to an ongoing boom in domestic demand.

This was, perhaps, the first indication that the US economy could be at the mercy of international capital flows over which policymakers had no direct control.

The bubble in equities could not be sustained.

While it lasted many people were happy to extol the wonders of the ‘new economy’.

There certainly was an improvement in productivity growth led by cutting-edge technologies, but, as time passed, the impact of these technologies on rising living standards began to fade.

Economic growth in the developed world slowed following the 2000 stock-market crash and would have been slower still in the absence of a global housing boom and a massive, and unsustainable, expansion of credit.

The belief in the wonders of new technologies was fuelled by a stock market that, for a while, seemed to defy the laws of gravity.

This became a circular process: the stock market went up because of new technologies, but investment in new technologies was forthcoming because the stock market was going up.

Bubbles burst.

The stock-market boom in the late 1990s, fuelled by capital inflows from Asia and other emerging economies, was no exception.

The Federal Reserve belatedly applied the monetary brakes, signalling its disagreement with those more optimistic investors who believed US economic growth might be sustained at a 4 per cent annual rate for evermore.

By past standards, interest rates didn’t rise very far.

They didn’t have to.

The message got through.

All those expectations of exuberant profits growth in the years to come began to fade and, as they did so, stock markets collapsed.

No matter how much capital was pouring into the US economy from Asia and other parts of the emerging world, ultimately reality triumphed over inflated stock-market aspirations.

Moreover, as the stock market plummeted, so the usual scams emerged, in the form of Enron, WorldCom and the rest.

Trust collapsed and equity markets were unable to recover their earlier poise.

Yet investors and policymakers failed to learn the lesson.

The hunt for yield did not disappear.

And with emerging economies building up ever-larger savings surpluses, distortions in global capital markets got worse, not better.

The belief in the pot of gold refused to go away.

Since equities couldn’t deliver the necessary returns, and government bond yields were ludicrously low, investors went in search of other assets that might do the trick.

As with any other market, an increase in demand for high-returning non-equity assets was met with an increase in supply.

Asset-backed securities, mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations and so on became the investments

du jour

.

Banks packaged up vast quantities of loans into these securities and either tucked them away under the mattress as off-balance-sheet items in the form of conduits and special investment vehicles (SIVs) or, instead, sold them off to other investors – insurance companies, pension funds, hedge funds and, in some cases, local councils – who, collectively, became known as the ‘shadow banking system’.

These institutions lent

money to the banks who, in turn, lent the money on to their customers.

These customers included, most obviously, sub-prime borrowers in the US.

Lenders did not restrict themselves to lending merely to US borrowers with questionable credit histories.

They also, increasingly, lent to customers within the emerging world.

After all, emerging economies were growing quickly and, therefore, seemed to have many of the attributes required to justify a ‘hunt for yield’.

For the daring investor, the opportunity to make high returns was there to be grabbed, notwithstanding the paltry long-run returns that had been made since the 1980s.

Some emerging economies – most obviously, those in Central and Eastern Europe – saw capital inflows rising much more quickly than capital outflows, leaving them with balance of payments current-account deficits.

Others coped with rising capital inflows by creating even bigger capital outflows, often in the form of rapidly rising foreign-exchange reserves.

China is a fine example of this reaction.

Between 1997 and 2008, for example, foreign direct-investment inflows into China rose by $723bn: simultaneously, foreign-exchange reserves (in effect, investments made abroad by China’s central bank for the benefit of the people) rose by $1,841bn.

6

China and other emerging nations became major participants in a global liquidity game played more by governments than by private institutions.

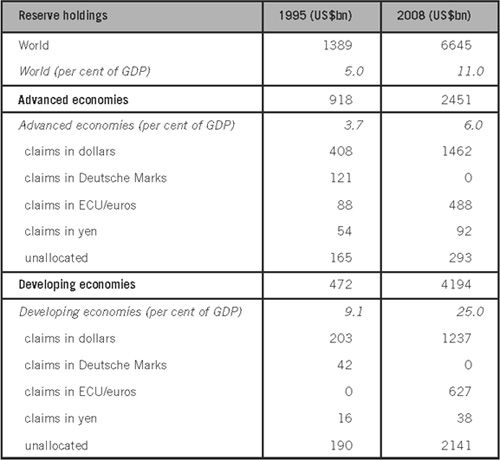

Some limited clues to the changing status of international capital markets, and the growing role of state investors and borrowers, comes from the IMF’s data on the currency composition of official foreign-exchange reserves (COFER), outlined in Figure

4.3.

In 1995, before the onset of the Asian crisis, global foreign-exchange holdings amounted to $1.4trn (around 5 per cent of global GDP).

Within the total, $0.9trn was held in the developed world (around 3.7 per cent of developed world GDP) with the remaining $0.5trn held in the emerging and developing economies (around 9.1 per cent of their GDP).

Figure 4.3:

The changing pattern of foreign-exchange reserve holdings

Source: IMF Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves

By 2008, the picture had radically changed.

Global foreign-exchange reserves had jumped to an extraordinary $6.7trn (around 11 per cent of global GDP).

Of this, $2.5trn was held in the developed world (around 6 per cent of developed world GDP) with $4.2trn held in the emerging and developing economies (around 25 per cent of their GDP).

Many of these reserves were ‘unallocated’ and hidden away within the emerging world.

Secrecy doesn’t help but, given that around 60 per cent of allocated emerging reserves

were held in dollars, there’s every chance that much of their mysterious $2.1trn was also dollar-denominated.

Assuming that the dollar share was, again, 60 per cent, overall holdings of dollars within emerging country foreign-exchange reserves would have amounted to $2.6trn, the equivalent of 15 per cent of emerging world GDP.

While large, these numbers almost certainly understate the seismic shift in capital markets that has taken place over the last twenty years.

Foreign-exchange reserves have risen rapidly, but so too have other forms of state ownership, as we shall see in Chapter 7 with the rise of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs).

Because the distinction between reserves and SWFs is so vague, the true size of government holdings of foreign assets is difficult to pin down.

For example, according to Bloomberg, Saudi Arabia’s reserve holdings amounted to just $27bn at the beginning of 2009, or just 0.4 per cent of the global total.

For a major oil producer which has run current-account surpluses for decades, these numbers appear implausibly low, suggesting that Saudi Arabia’s overseas assets are locked away in other forms.

In many emerging nations, the distinction between state-owned and privately owned assets is far from clear.

While the official international savings of emerging economies have risen dramatically, so too have the international borrowings of the US government.

In 1950, US federal debt outstanding amounted to around $257bn.

At approaching 100 per cent of US national income, this was a huge legacy of the military expenditures associated with the Second World War.

Almost all this debt was funded by Americans who were happy to lend to their government.

Less than 2 per cent of the total was funded by foreigners, partly because of a wave of capital and foreign-exchange controls throughout the world.

By 2008, US government debt had risen to $9.6trn.

As a share of national income, this stood at 68 per cent, lower than the immediate post-war extremes but, nevertheless, a sizeable increase compared with the 1981 trough of 33 per cent.

Foreign participation had grown

hugely.

The amount of US government debt held by foreign lenders had risen to $3.2trn, or around one-third of the amount outstanding.

Foreigners had also piled into bonds issued by, for example, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the home-loan specialists.

These and other government-sponsored enterprises were assumed to have an implicit US government guarantee, making the paper they issued about as safe as US Treasuries (in the light of the 2008 financial meltdown and the taxpayer-funded bailout that followed, this proved to be an accurate assumption).

By 2008, foreigners owned $1.4trn of this paper, up from hardly anything in 1950.

They also held $2.8trn of ‘corporate’ bonds, most of which turned out to be mortgage-backed securities, ultimately dependent on the health of the US housing market and the US banking system.

Many of these pieces of paper also had an implicit US taxpayer guarantee, at least to the extent that the banking bailouts at the height of the credit crunch required a huge injection of taxpayers’ money to buy up the ‘toxic’ assets hidden away in banks’ balance sheets in the form of conduits and SIVs.

These numbers are huge.

Over 50 per cent of US assets by value held by foreigners are these IOUs, while fewer than 13 per cent of foreign-owned US assets are equities and only around 20 per cent are in the form of foreign direct investment.

Seen this way, the current and future US taxpayer is enormously in debt to the rest of the world and, in particular, to foreign governments.

Around 50 per cent of new US debt issued each and every year is now purchased by foreign investors.

Many of these investors are state entities.

We thus have a global capital market dominated by borrowing and lending governments, not by the millions of investors required by a free market.

The action of both borrowing and lending governments has ensured the creation of a ‘virtuous’ circle of excess liquidity.

Too many

emerging economies wanted to run large current-account surpluses and resist exchange-rate appreciation.

To do so, they lent to Western governments through rising foreign-exchange reserves that were often invested in liquid government paper, lowering the yields on this paper.

Too many investors in developed markets were happy to chase higher yields on riskier assets, disregarding the associated dangers.

As they did so, they allowed banks to raise funds well beyond their deposits through the creation of securitized products.

Many of these funds were lent to US households with questionable credit histories in the form of sub-prime mortgages.

Some of the funds raised, though, were lent back to the emerging economies.