LOSING CONTROL (8 page)

Authors: Stephen D. King

Of course, this is not just one-way traffic.

US concerns about Chinese economic muscle do not stem from China’s growing role as a market for US exports.

Instead, they are a reflection of China’s growing penetration in US markets.

For every dollar of US exports to China, around $4 comes back the other way, giving an overall deficit on the US current account position with China of $308bn in 2008.

China has a huge bilateral trade surplus with the US notwithstanding the substantial increase in US exports to China in recent years.

China’s trade surplus, in turn, has become a major source of friction between these two great powers.

11

The position is somewhat ironic.

In the 1980s, when China’s subsequent economic success was no more than a distant dream, the US became concerned about other trading relationships.

Before the Berlin Wall came down, the country generating the biggest concerns was Japan.

America’s bilateral deficit with Japan had been steadily expanding through the 1980s, helped along in the first half of that decade by a massive appreciation of the US dollar, which had dampened the competitive position of US exporters.

Japan came under tremendous pressure to open up its domestic markets which, for services in particular, had been closed to foreign competitors.

As far as the US authorities were concerned, Japan was pursuing a mercantilist policy that threatened the fabric of economic life in the US.

Germany was tarred with the same brush.

In a conversation in the late 1980s, an American economist made the absurd claim to me that ‘what the Japanese and Germans are trying to do to us economically today is what they failed to do to us militarily during World War Two’.

Those who believe that the US always happily embraces free trade need to wake up.

Isolationism and exceptionalism are characteristics that have stuck like leeches to the US nation throughout its history.

In Chapter 10, I discuss this issue in more

detail; for the time being, it’s worth noting that free movement of goods and capital across borders is far from guaranteed.

In the 1980s, the US had a huge bilateral trade deficit with Japan.

It still does.

12

Yet concerns about Japan’s industrial muscle have faded even though Toyota, for example, is a far more successful car manufacturer than its American counterparts.

Why has Japan faded from view?

The answer doubtless lies with Japan’s multi-year economic stagnation.

The biggest perceived threat to American economic prosperity in the 1980s is now regarded as only a second-tier economic power.

US diplomatic interest has shifted to the other side of the East China Sea.

China may not be as wealthy per capita as Japan, but it’s the world’s biggest consumer of a variety of industrial raw materials, it’s growing very quickly and, unlike Japan, it has nuclear weapons.

China bestraddles the global stage in ways unimaginable only a few decades ago.

Japan, meanwhile, is merely a shadow of its former economic self.

America’s fear is ultimately that the US could be heading the same way as Japan.

One possible defence of the comparative-advantage argument is to suggest that the US, unlike Japan, can more easily cope with the rise of China because America’s economy is unusually flexible.

It’s worth considering, for example, the implications of heightened foreign direct investment for the relative shares of different types of economic activity in the developed and the emerging worlds.

One particularly significant change in recent decades has been a wholesale shift in manufacturing capacity from the developed to the emerging world.

It’s no surprise that, these days, Germany and Japan regard emerging economies as some of their biggest customers: as the world’s most important producers of capital goods, sustained

increases in plant and machinery investment within the emerging world are good news for the likes of Siemens and Komatsu.

Overall, the share of global industrial ‘added value’ coming from the developed nations has dropped from 68.3 per cent in 1971 to 51.9 per cent in 2008, while the share accruing to Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC), has risen from 2.6 to 16.5 per cent over the same period (similar figures apply to capital spending).

For GDP as a whole, the G7 share has fallen more moderately from 70.5 per cent in 1971 to 61.1 per cent in 2008, with the share for China et al.

rising from 3.3 to 11.6 per cent over the period:

13

in other words, the developed nations have moved away from manufacturing while the BRICs have become increasingly dependent on it.

The Ricardian interpretation of these developments is simple.

All that’s happened is that each area of the world has focused on its comparative advantage.

As barriers came down, there was swift recognition of the huge cost advantage offered by potential manufacturing workers in the emerging world.

Many of these people were, in effect, underemployed in the agricultural sector.

Their drift into urban factories both raised productivity in the agricultural sector (fewer workers but a similar output) while raising incomes as a whole because, on average, productivity is higher in manufacturing than in agriculture.

14

But if the emerging economies are now focused on manufacturing production, a Ricardian interpretation requires the developed world to specialize in something else.

The answer, it seems, has been a massive growth in financial services (alongside design, the media and other service industries).

In effect, emerging economies make things but capital markets in the developed world determine what things should be made through their banks, stock markets and bond markets.

Think of China, for example, as a naive saver who regularly deposits his income into the local bank which, for the purposes of this argument, I’ll call American Thrift Inc.

As a naive saver, China does not want a particularly high return on his savings: instead, he

just wants to know that he can get access to those savings at a moment’s notice.

American Thrift Inc.

offers a very modest return to its depositors but then takes the money to invest in higher-returning opportunities elsewhere.

This, of course, is not quite the whole picture.

While China treats America as its bank, China invests largely in Treasuries rather than in any particular financial establishment.

As we shall see in Chapter 4, the higher demand for Treasuries raises the price of Treasuries and, thus, lowers the yield.

This lower level of interest rates makes other investments seem more attractive, including investments by US multinationals into China.

The increased flow of foreign direct investment into China is profitable for US multinationals, creates additional Chinese jobs and, at the same time, allows the American financial-services industry to expand.

What better illustration could there be of the benefits of comparative advantage?

Unfortunately, this is not all good news.

The argument works only if there are no distortions created as a result of treating the US as China’s bank.

Yet there are distortions aplenty.

Although the Chinese deposit their savings with the US, they have no say over how those savings are then invested.

While US companies might choose to invest in China, they could just as easily invest in a domestic housing boom (as, in fact, they did in the early years of the twenty-first century).

For those lucky enough to be working in financial markets during the boom years, the winning mentality prevailed.

But as the dependency on financial systems as sources of income and wealth has increased in the developed world, so the risk of financial crises may have risen.

As manufacturing has headed elsewhere, the developed world has increasingly found its comparative advantage to be in the world of financial roulette.

As we discovered in 2008 and 2009, this was, perhaps, a gamble that did not pay off.

Indeed, the outsourcing and off-shoring synonymous with the rise of the emerging world have revealed underlying weaknesses in

the developed economies.

Rent-seeking behaviour has increased in the financial industry where monetary rewards have, in some cases, soared into the stratosphere.

Yet the returns delivered by the financial industry have been generally poor, at least since the 1990s.

As we’ll see in Chapter 6, the vast majority of people in the West have not substantially gained from increased globalization.

Moreover, to the extent that weaknesses within the financial system, revealed in 2008 and 2009, will have to be paid for by current and future taxpayers, the ultimate benefits of globalization for the West have either already been taken off the table by those in the financial world who were lucky or, instead, have been significantly overstated.

The rapid growth of the financial services industry appears both to have masked a competitive loss in other areas of economic endeavour and to have created a huge future tax burden.

The implications of this will be explored more fully in the following chapters.

At this stage, however, it’s worth emphasizing that the changing patterns of trade seen since the 1980s do not reflect the simple homilies of comparative advantage.

We are only now beginning to see the full consequences of the changing trading patterns associated with the rise of the emerging economies.

Parts of the developed world have swapped the cyclicality of manufacturing activity for the instability of high finance.

Other parts of the developed world have stagnated.

Companies have, rightly, taken advantage of the new investment opportunities that have opened up around the world.

Governments, however, have been slow to understand the full implications of outsourcing, off-shoring and all the rest.

They’ve ended up with economies that have developed an alarming taste for cowboy capitalism.

The commitment to free trade, where it exists, is, in general, admirable.

The failure to think about the consequences of restructuring for broader economic stability is not so admirable.

As emerging economies have increasingly specialized in the activities

that used to take place in the West, the developed world has struggled to work out what to do next.

In Japan, the cost has been seen in economic stagnation.

In the US and the UK, the costs can be seen in the form of inflated financial sectors operating in a global casino which, unlike Las Vegas, has no hard-and-fast rules.

As Chapter 4 reveals, capital markets have as a result become increasingly unstable.

INTERNATIONAL ROULETTE: ANARCHY IN CAPITAL MARKETS

While emerging economies have had a huge influence on capital market performance, it has not been the influence expected by the majority of investors.

Many thought a gold mine of investment opportunities awaited them.

On the whole, these hopes have been dashed.

There has been no gold mine.

Instead, we have been living through a modern-day version of the Californian gold rush.

Too often, only fool’s gold has been on offer.

Capital markets have not delivered decent returns while financial systems overall have become increasingly unhinged.

The gravitational pull of the emerging nations has left interest rates and the prices of a wide range of financial and real assets increasingly warped.

The consequence has been a vast increase in financial-market volatility and a reduction in rates of return.

As the emerging economies awoke from their decades and, in some cases, centuries of economic hibernation, corporate investors and

fund managers around the world licked their lips.

Companies saw tremendous opportunities ahead of them.

No longer were their customers and workers confined to the developed world.

Corporate executives were, instead, faced with a brave new world offering higher sales volumes at lower cost and, hence, higher profit.

Fund managers began to offer new products tailored to the exciting new opportunities available in the emerging world.

In the summer of 2009, for example, Fidelity International – one of the world’s biggest and most successful fund managers – offered to investors a total of well over thirty separate funds tailored specifically to emerging markets.

As for individual savers, they could benefit in one of two ways.

Either they could buy one of the thousands of funds that directly invested in emerging world companies; or, instead, they could buy shares in companies based in the developed world, which, in turn, would invest the additional funds in exciting new opportunities in the emerging world.

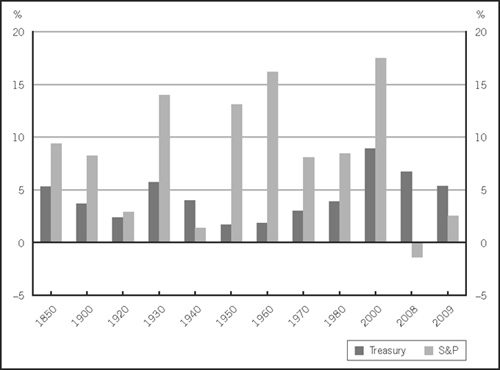

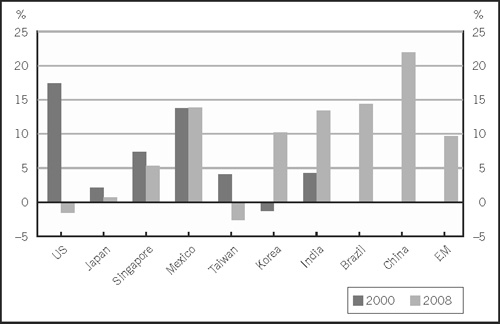

Yet for investors, it’s been a roller-coaster ride with more downs than ups, particularly since the beginning of the new millennium.

While some years have offered spectacular returns in specific markets, overall returns have been poor.

In the ten years ending in 2008 (a year in which equities collapsed) or 2009 (when equities rebounded), investors would have been better off investing in safe, boring, US Treasuries – simple claims on future US taxpayers – than in US equities or, indeed, in the equities of many emerging markets (see Figures

4.1

and

4.2

).

Given that many profit-hungry US companies chose to invest all over the world – including its emerging parts – this is a remarkable and historically unprecedented result.

Partly, it reflects the increasing instability of the financial system as a whole.

Following the collapse of the Berlin Wall, crisis layered upon crisis: an early 1990s credit crunch, the 1992 European exchange-rate crisis, the Mexican ‘tequila’ crisis, the Asian crisis, the Russian and Argentine defaults, the dot.com bubble and subsequent bust, the sub-prime crisis and, of course, the global meltdown that followed.

Figure 4.1:

10-year returns for US government bonds and US equities

Source: HSBC

Figure 4.2:

10-year annualized returns across developed and emerging nations

Source: HSBC.

Returns data for the ten years to 2000 are not available for Brazil and China and, hence, for the emerging nations as a whole.

EM refers to emerging markets and is an aggregate measure of their performance.

Capital markets bring together savers and borrowers.

They allow us to plan for our futures.

They enable us to smooth our consumption patterns over our lifetimes (and, if bequests are included, beyond our lifetimes).

They help determine the amount, and type, of investment in an economy.

They link the real economy with the financial economy.

Capital market participants – bankers, fund managers, private- equity investors and other ‘go-betweens’ – package their products in all sorts of ways, ranging from simple bank deposits and loans through to the ever-more complex instruments that make up the lexicon of international finance: syndicated loans, equities, corporate bonds, commercial paper, asset-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations and structured products.

Ultimately, each of these products offers a claim on future economic wealth (or, put another way, a reward for abstinence today).

Banks provide loans in exchange for an interest payment.

Shareholders hold equities because they expect a dividend or a capital gain.

Issuers of asset-backed securities provide a return in exchange for the apparent protection associated with the underlying asset.

That most people have no idea of what these products are is one of the wonderful tricks of modern international finance.

Ultimately, savers end up buying products they often don’t understand.

Not surprisingly, the business of global capital markets has, over the years, attracted more than its fair share of snake-oil salesmen.

There is no shortage of rent-seeking behaviour in the capital markets.

Yet despite these difficulties, we desperately want our capital markets to perform well.

With baby boomers approaching retirement, the developed world is facing new challenges.

The proportion of people in work is diminishing.

With fewer workers, how will it be possible to deliver the income needed to feed not just the workers themselves but also the increasing numbers of people in retirement?

In recent years, the answer has come in the form of a ‘hunt for yield’, a search for a range of magic assets that would either deliver higher interest rates or dividends than in the past or, alternatively, produce higher capital returns than before without any additional risk.

There is, apparently, a pot of gold at the end of the investment rainbow.

Even for those countries facing tremendous economic challenges this belief is difficult to shake off.

The pressure to earn a high rate of return is intense, even if the domestic economy is stagnant.

During the 1990s, I was constantly amazed by Japanese fund managers who believed they could squeeze double-digit returns from an economy that had lost the ability to expand.

On paper, the arrival on the global economic stage of the emerging economies thus seemed to offer manna from heaven.

Suddenly, arthritic growth in the developed world was no longer a constraint on capital returns.

Instead, the West could invest in the emerging world.

Companies could produce goods more cheaply and widen their customer base, thereby boosting their profits and keeping their shareholders and bank managers happy.

All in all, the emerging economies gave a shot in the arm to global growth, implying higher future levels of output and, hence, higher capital returns.

You could almost hear the collective sigh of relief.

With China opening its borders, with the Soviet Union’s collapse triggering

outbreaks of capitalist endeavour across Eastern Europe and with India deciding its long-term interests were best served by embracing the market economy as opposed to its earlier flirtations with socialism, it suddenly appeared that ageing Westerners would no longer see their living standards coming under downward pressure.

Wrinkly Americans and greying Europeans would be able to head off to Naples Beach or Cannes for their summer holidays, happy in the knowledge that wealth accumulation was safe and sound, given the new opportunities presenting themselves in the emerging economies.

That, at least, was the theory.

The practice has been entirely different.

The financial industry takes pride in the idea that its many skilled practitioners are able to deliver returns superior to those available to ordinary folk who probably don’t know the difference between an equity, a corporate bond and a structured product.

Yet the various financial mishaps of recent years paint an entirely different picture.

It is extraordinary that savers would have been better off leaving their investments in safe US Treasuries than investing in some of the products that, supposedly, deliver superior returns over a longer time period.

For every emerging-market investment that appears to have performed well, others have performed poorly.

As for the US, the recent ups and downs in its financial markets offer a match for Japan and its lost decades.

This is a puzzling outcome.

After all, the emerging economies have delivered rapid growth since the 1980s, expanding at a rate two or three times faster than the typical pace seen in the industrialized world.

If growth has been so good for the vast majority of the time, surely it should have been easy to unearth profitable investment opportunities?

Either investors could have put their money directly

into emerging markets or, instead, they could have invested in companies that, in turn, had strategic profitable aims in the emerging world.

The hunt for yield, however, went off in an altogether different direction.

It was as if someone had rearranged all the road signs, sending travellers to entirely inappropriate destinations.

The proof comes from the emergence of the so-called ‘global imbalances’.

If emerging economies offered such wonderful investment prospects, a reasonable conclusion might be that savings would accumulate in the developed world and then flow into investment prospects in the emerging world.

That, after all, was the nineteenth-century model of globalization, with savings from the UK heading to emerging nations to take advantage of exciting investment opportunities.

In this ‘win-win’ situation, capital inflows would, in theory, fuel higher growth in emerging markets, generating rising living standards for more and more people.

Meanwhile, the new investment opportunities would enable Western companies to make higher profits, thereby satisfying the hunt for yield for Western holders of capital.

The outcome has been exactly the opposite.

On balance, savings and, hence, capital have flowed not from the developed world to the emerging world but, instead, from the emerging world to the developed world.

The US, for example, has run a bigger and bigger current-account deficit over the last three decades (admittedly with the occasional interruption for a recession).

To do so – and it’s no more than a simple rule of accounting – the US has had to attract increasing amounts of capital from abroad.

In the 1980s, the primary sources of this capital were Japan and Germany.

At that time, global imbalances were the G7’s problem.

The inability of the G7 to reach any kind of credible agreement, notwithstanding the Plaza and Louvre accords in 1985 and 1987 respectively, led to upheavals in currency markets and, eventually, the 1987 stock-market crash.

1

Japan and Germany remain important providers of capital, but from the mid-1990s onwards the really big suppliers have been China, the Middle East, Russia and an assortment of other emerging economies.