Lost to the West (37 page)

Authors: Lars Brownworth

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Rome, #Civilization

*

One of Alexius’s more unsung contributions to Byzantium was in restoring the gold content of its coins and thereby ending the vicious inflation that was crippling its economy.

*

Though his body was carried off and interred in Venosa, Italy, the charming town of Fiscardo—where he died—still bears a corrupted form of his name.

*

He managed to escape from Byzantine territory by concealing himself in a coffin with a decaying rooster to provide an appropriate aroma. While his supporters wept and dressed in mourning clothes, Bohemond’s “coffin” was smuggled onto a ship and delivered safely to Rome.

*

Among them was his daughter Anna Comnena, who wrote the

Alexiad

—perhaps the most entertaining Byzantine account of the life and times of Alexius.

†

The church is still there, tucked unobtrusively into the surrounding masonry, and though it’s now in ruins (and not entirely uninhabited), no tomb has ever been found. Perhaps Alexius sleeps there still in some undiscovered vault, dreaming of happier days.

*

Unlike earlier Roman emperors who entered Olympic games or gladiatorial contests assured of victory (Nero, Commodus), Manuel was apparently quite proficient at jousting. According to Byzantine accounts, in one tournament he managed to unhorse two famous Italian knights.

*

The Germans elected to ignore Manuel’s advice and march by the quickest route and were ambushed almost immediately, virtually eliminating the Teutonic army from the struggle. Under the command of the French, the remaining crusaders made the mind-boggling decision to attack Damascus—the one Muslim power that was allied with them—invading at the height of summer. By July 28, 1148, after only five days of a disastrous siege, the various leaders abandoned the attempt in disgust and returned to their homes.

22

S

WORDS

T

HAT

D

RIP WITH

C

HRISTIAN

B

LOOD

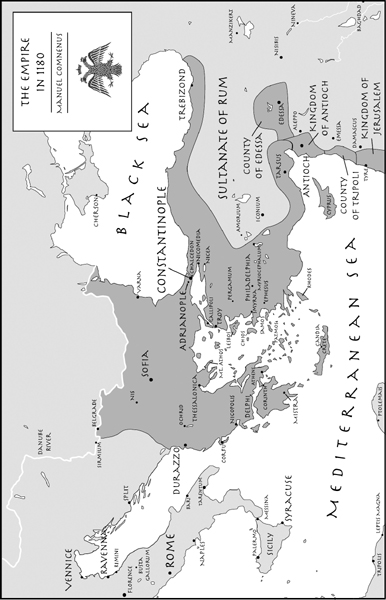

T

he speed at which the empire collapsed took even its citizens by surprise. In the past when Byzantium was threatened, great leaders had arrived to save it, but now it seemed as if the imperial stage was conspicuously absent of statesmen. Manuel’s twelve-year-old son, Alexius II, was obviously incapable of dealing with the looming problems facing the empire and could only watch as the Turks advanced unopposed in Asia Minor, the brilliant Stefan Nemanja declared independence for Serbia, and the opportunistic king of Hungary detached Dalmatia and Bosnia from the empire. Some relief arrived when Manuel’s cousin Andronicus seized the throne, but he proved a deeply flawed savior, fully earning his nickname of Andronicus the Terrible.

*

Gifted with all the brilliance but none of the restraint of his family, he understood only violence, and though he cut down on corruption, his rule quickly descended into a reign of terror. Nearly demented with paranoia, he forced Manuel’s son to sign his own death sentence, had him executed, and, in a final act of depravity, married the eleven-year-old widow. After two years, the people of the capital could take no more and in suitably violent fashion put a new emperor on the throne.

For all his faults, Andronicus the Terrible had at least preserved some sort of central authority in the empire. Isaac Angelus—the man who took his place—founded the dynasty that would throw away the empire’s remaining strength and preside over its complete breakup. Unaccustomed to enforcing his will on others, Isaac sat back while the authority of the central government crumbled. Governors became virtually independent, and friend and foe alike began to realize that Constantinople was impotent. The Aegean and Ionian islands, safely outside the reach of the decaying navy, rebelled almost immediately, and the Balkans slipped forever out of Byzantium’s grasp.

The empire’s misery was compounded by the worsening situation in the Christian East. The Muslim world was united under the brilliant leadership of a Kurdish sultan named Saladin, and the squabbling crusader kingdoms could put up little resistance. In 1187, Jerusalem fell, and inevitably the West launched another Crusade to retake it, again using Constantinople as a staging point. The presence of foreign armies passing through the capital was dangerous at the best of times, but Isaac would have been hard pressed to have handled the situation more poorly. When the German ambassadors arrived to discuss transport to Asia Minor, Isaac panicked and threw them into prison. The enraged German emperor Frederick Barbarossa threatened to turn the Crusade against Constantinople, and the blustering Isaac caved completely, immediately freeing the prisoners and showering them with gold and apologies.

This shameful behavior went a long way toward confirming the abysmal Byzantine reputation in the West and thoroughly disgusted the emperor’s beleaguered subjects. Whatever support Isaac had left crumbled away when he made the insane decision to officially disband the imperial navy and entrust the empire’s sea defenses to Venice. Seeing his moment to strike, Isaac’s younger brother Alexius III ambushed the emperor and his son and—after blinding the emperor—threw them both into the darkest prison he could find.

Unfortunately for the empire, the new emperor proved to be a

good deal worse than his brother. Capturing the throne had taken most of his energy, and now he couldn’t be bothered to actually govern. While the Turks marched up the Byzantine coastline in Asia Minor and Bulgaria expanded in the west, Alexius III busied himself in a search for money to fund his lavish parties—even stooping in his greed to stripping the old imperial tombs of their golden ornaments.

As the emperor plundered his own city, Isaac in his black cell was dreaming of revenge. His own escape was impossible and, since he was blind, quite pointless, but if his son Alexius IV could break free, there might yet be justice. Somehow the old emperor made contact with his supporters in the city, and in 1201, two Pisan merchants were able to smuggle the young prince out. Fleeing to Hungary, Alexius IV stumbled onto an unexpected sight: a new crusading army was on the march.

T

he Third Crusade hadn’t been a success. After sacking the Seljuk capital of Iconium, the fearsome German emperor Frederick Barbarossa had drowned in a freak accident while crossing the Saleph River in southeastern Anatolia.

*

Without him, the German army panicked and melted away, with some soldiers even committing suicide in their desperation. The English and French armies, on the other hand, arrived in much better condition, and—led by the dashing Richard the Lion-Hearted—they were ready to fight. Repairing the damage done to the crusader kingdoms was tedious work, though, and Richard had no patience. After a year spent conquering the coastline, he was terribly bored with the entire thing. Jerusalem seemed as unreachable as ever, the crusaders were squabbling mercilessly, and the French king (he rightly suspected) was plotting against him.

After hastily patching up a truce with his Muslim rival—the gallant Saladin—Richard sailed off to find another adventure, announcing before he left that any future Crusade should be directed against Egypt—the “Achilles’ heel” of the East.

Richard’s reputation was so great in Europe that the German leaders of the Fourth Crusade decided to take his advice and capture Jerusalem via Egypt. This, of course, meant that the entire army would need to be transported across the Mediterranean, and there was only one place that could provide enough ships for an entire Crusade. Gathering their courts, the princes of Europe headed for Venice.

The islands in the Lagoon of Venice had a long and tangled history with the empire. Originally composed of refugees from the Lombard invasion of Italy in the sixth century, the collection of islands that made up Venice was administered by the imperial governor of Ravenna and drew heavily on the Byzantine culture around it. The church on its oldest island, Torcello, had been paid for by the emperor Heraclius, the main cathedral of Saint Mark’s was a loose replica of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, and Venetian sons and daughters were regularly sent for education—or spouses—to Byzantium. Even the title of “doge” was a corruption of the original imperial title of

dux

, or duke. Recent years, however, had seen more competition than cooperation between the republic and the empire, and the latest heavy-handed treatment of Venetian traders by the Comnenian emperors still grated on Italian nerves.

This was especially true of the doge who greeted the crusaders in 1202. He was none other than Enrico Dandolo—the ambassador who had vainly protested the emperor Manuel’s seizure of all Venetian property within the Byzantine Empire thirty years before. Now in his nineties and completely blind, the old doge masked a fierce intelligence and an iron will behind his seemingly frail frame. Here was an opportunity not to be missed for the calculating Dandolo. Venetian claims for lost property were still outstanding, and the insults endured at the hands of the empire had lost nothing in the intervening years. Now, at last, however, was a chance of revenge.

First, he agreed to build the necessary ships, but only in return for an enormous sum. Unfortunately for the crusaders, turnout for the expedition was embarrassingly low, and they could only come up with little more than half of what they owed. Dandolo shrewdly cut off food and water to the Christian army now trapped on the lagoon awaiting its navy, and when they were appropriately softened up, he smoothly proposed a solution. The Kingdom of Hungary had recently ousted Venice from its protectorate over the city of Zara on the Dalmatian coast. If the crusaders would only consent to restoring this city to its rightful owners, payment of the sum could be postponed. The pope instantly forbid this blatant hijacking of the Crusade, but the crusaders had little choice. A few soldiers trickled away, disgusted by the thought of attacking a Christian city, but the majority uneasily boarded their ships and set sail. The terrified citizens of Zara, bewildered that they were under attack by the soldiers of Christ, desperately hung crosses from the walls, but it was to no avail. The city was broken into and thoroughly looted; it seemed as if crusading zeal could sink no lower.

It was at Zara that the fugitive Alexius IV joined the Crusade. Desperate for support, he was willing to say anything to free his father and overthrow his uncle, and he rashly promised to add ten thousand soldiers to the Crusade and pay everyone at least three times the money owed to Venice. As a final incentive, he even proposed to place the Byzantine church under Rome’s control in return for the Crusade’s help in recovering his crown.

Perhaps no single conversation in its history ever did the empire more harm. Enrico Dandolo knew perfectly well that the Byzantine prince’s wild offers were pure fantasy. Central authority in the empire had been collapsing for decades, and the frequent revolts combined with a corrupt bureaucracy incapable of collecting taxes made it virtually impossible to raise any money—much less the lavish sums offered by Alexius IV. The old doge, however, sitting amid the ruins of Zara, had begun to dream of a much larger prize, and the foolish Byzantine would make the perfect tool. He had probably never intended to attack Egypt at all, since at that moment his ambassadors

were concluding a lucrative trade agreement in Cairo. Dandolo ostensibly agreed to redirect the Crusade to Constantinople, and to those soldiers squeamish about attacking the premier Christian city, he smoothly pointed out that the Greeks were heretics and that by placing Alexius IV on the throne they would be restoring the unity of the church. The pope frantically excommunicated anyone who considered the idea, and some drifted disgustedly away; but the Venetian doge was persuasive, and again most of the soldiers dutifully boarded their ships. The Fourth Crusade was now firmly under Dandolo’s control.