Lost to the West (40 page)

Authors: Lars Brownworth

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Rome, #Civilization

Michael VIII never lived to see the death of his great enemy. With the threat of western aggression gone, the despot of Epirus was once again asserting his independence, and the emperor was determined to bring him into line. The fifty-eight-year-old emperor again

led his troops toward battle, but he had gotten no farther than Thrace when he fell seriously ill. Thinking as always of his responsibilities, the dying emperor proclaimed his son Andronicus II to be his successor, and expired quietly in the first days of December.

He had been among Byzantium’s greatest emperors, restoring its capital and dominating the politics of the Mediterranean. Without him, the empire would certainly have fallen to Charles of Anjou—or any number of watching enemies—and the Byzantine light would have been extinguished, its immense learning dispersed among a West not yet ready to receive it. Instead, Michael VIII had deftly outmaneuvered his enemies, founding in the process the longest-lasting dynasty in the history of the Roman Empire. Nearly two hundred years later, a member of his family would still be sitting on the throne of Byzantium, fighting the same battle of survival—albeit with much longer odds. Michael had done what he could to repair the imperial wreckage. He left behind valuable tools to continue the recovery: a small but disciplined army, a reasonably full treasury, and a refurbished navy. But for the savior of the empire, no gratitude awaited. Excommunicated by the pope, he died a heretic to the Catholic West and a traitor to the Orthodox East. His son buried him without ceremony or consecration in a simple, unmarked grave. Michael VIII’s affronted subjects, however, would all too soon have reason to miss him. If Byzantium looked strong at his death, it was only because his brilliance had made it so. Without a strong army or reliable allies, its power was now purely diplomatic, and it needed hands as skillful as Michael’s to guide it. Unfortunately for the empire, however, few of Michael’s successors would prove worthy of him.

*

Exactly eight hundred years later, in 2004, Pope John Paul II apologized—though the Fourth Crusade was hardly the fault of the pontiff—to the patriarch of Constantinople when the latter paid a visit to the Vatican, expressing pain and disgust even at a distance of eight centuries.

*

Virtually the only armed opposition came from a local brigand named Leo Sgurus. After four years of struggle Leo was trapped on top of the acropolis of Corinth, and, rather than surrender, he decided—in a scene worthy of Hollywood—to commit suicide by riding his horse over the side of the citadel.

*

The pope is best known to posterity for his role in the life of a young Italian adventurer. On his election in 1271, Gregory received a letter from Kublai Khan asking for oil from a lamp in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The pontiff entrusted it to the young Marco Polo—whose lively account of the journey became one of the most famous books of the Middle Ages.

24

T

HE

B

RILLIANT

S

UNSET

“Qui desiderat pacem, praeparet belium.”

“If you want peace, prepare for war.”

—VEGETIUS

T

he last two centuries of Byzantine history make, for the most part, rather discouraging reading. Against an increasingly hopeless backdrop, petty emperors waged destructive internal squabbles while the empire crumbled, reducing the once-proud state to a mere caricature of itself. There were, however, small moments of light to pierce the advancing gloom, rare individuals of courage and determination, struggling against the overwhelming odds, knowing full well that they were doomed. As the empire edged toward extinction, a cultural flowering occurred, a brilliant explosion of art, architecture, and science as if the Byzantine world was rushing to express itself before its voice was forever silenced. Sophisticated hospitals were built with both male and female doctors, and young medical students were given access to cadavers to learn the human body by dissection. Byzantine astronomers postulated on the spherical shape of the world and held seminars to discuss how light appeared to move faster than sound.

For the most part these advancing fields of physics, astronomy, and mathematics managed to peacefully coexist with the increasingly mystic Byzantine Church, but there were occasional tensions. The noted fourteenth-century scholar George Plethon composed hymns to the Olympian gods, and even went so far as suggesting a revival of

ancient paganism.

*

While this certainly didn’t help the reputation of the sciences and tended to confirm the suspicion that excessive study in some fields weakened the moral fiber, Byzantine society at large remained remarkably open to new ideas. This spirit was seen most vividly in the decorations and new buildings of the capital. Perhaps the impoverished empire could no longer build on the grand scale of the Hagia Sophia, or even the more modest levels of the Macedonian dynasty, but what it lacked in splendor it made up for in originality. In Constantinople, a wealthy noble named Theodore Metochites embellished the church of the Chora Monastery with vivid frescoes and haunting mosaics, departing from the staid forms of past imperial art in a way that still has the power to catch the breath today. The Ottoman shadow may have been looming over the city, but even the threat of extinction couldn’t cow the Byzantine spirit.

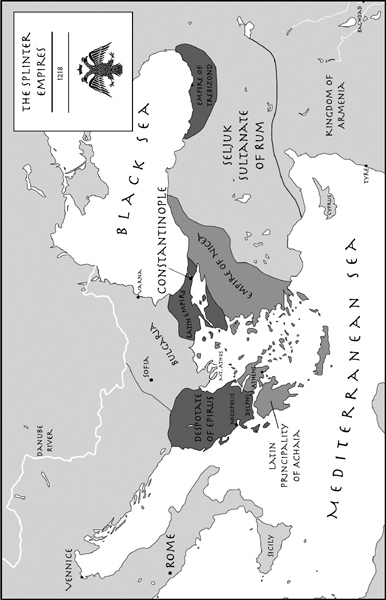

Ironically enough, it was partly Michael VIII’s glorious reconquest of Constantinople that hastened the collapse. Once restored to their rightful capital, the focus of the Byzantine leaders shifted back to Europe. Concentrating on the all-important city, the myopic emperors turned their backs on Asia Minor, where the balance of power was rapidly changing. The Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258 had broken the back of Seljuk power and a massive influx of Turkic tribes had come streaming in to fill the vacuum.

†

One of these groups, led by an extraordinary warlord named Osman, united several tribes and crossed into Byzantine territory. Calling his men “Gazi” warriors—the “swords of God”—Osman led a jihad aimed at nothing less than the

capture of Constantinople. The terrified Byzantine population of Anatolia fled at his approach and was replaced with Turkish settlers, largely extinguishing the Greek presence in Asia Minor. After a short struggle, the ancient city of Ephesus fell and Osman’s troops—now calling themselves Ottoman in his honor—shattered the weakened imperial army. Under his son Orhan, they took Bursa, at the western end of the Silk Road just across the Golden Horn from the capital, and then Nicaea and Nicomedia as well. Soon all that was left of the empire in Asia was Philadelphia and remote Trebizond on the Black Sea coast. Ottoman warriors could now stand in the waters of the Propontis and see the fluttering banners hanging from the churches and palaces of fabled Constantinople. The storied city was almost within their grasp. All they needed now was a way across.

Incredibly enough, this was conveniently provided by the Byzantines themselves, who seemed more interested in fighting over the fragments of their empire than protecting it from the obvious threat. By 1347, what was left of Byzantium was devolving into something resembling class warfare. A rebel patrician named John Cantacuzenus was attempting to seize the throne, and its current occupant responded by waging a successful public-relations war that branded John as a reactionary—the embodiment of the privileged class that had brought such ruin to the empire.

*

Across the empire, indignant cities expelled his troops. The citizens of Adrianople, anticipating the French Revolution by more than four centuries, massacred every aristocrat they could find and appointed a commune to rule the city.

Thrown back on his heels, Cantacuzenus invited the Turks into Europe, hoping to use their strength to seize Constantinople. The deal won Cantacuzenus his crown, but was disastrous for Europe, as what started as a trickle of Ottoman soldiers all too quickly became a

flood.

*

As the Turks crossed the Hellespont in ever-greater numbers to ravage Thrace, the bubonic plague returned to Constantinople after an absence of six centuries, adding the miseries of disease to the horrors of war. Spreading as it had before in the bodies of fleas and rats, it claimed the lives—according to one terrified account—of nearly 90 percent of the population.

†

The one consolation for the huddled, miserable inhabitants of Byzantine Thrace was that the Turks had come as raiders, not settlers. Each winter, the marauding Ottomans returned across the Bosporus to their Asian heartland and left the weary peasants in peace. But even that small comfort disappeared in 1354. On the morning of March 2, a tremendous earthquake shattered the walls of Gallipoli, reducing the city to rubble. Declaring it to be a sign from God, the Turks swept in, settling their women and children and evicting the few Byzantines who hadn’t already fled. The emperor frantically offered them a large amount of money to leave, but their emir responded that since Allah had given them the city, to leave would be a sign of impiety. The Ottomans had gained their first toehold in Europe, and they didn’t intend to leave. Jihadists flooded across from Asia, and the weak and devastated Thrace fell easy victim to their advance. After a probing stab in 1359 convinced the Ottomans that Constantinople was out of reach, they simply surged around it. Three years later, Adrianople fell, surrounding the capital of eastern Christendom in an Islamic sea.

The Turkish emir left little doubt of his intentions. Moving the capital of the Ottoman Empire into Europe, he sold part of Adrianople’s population into slavery and replaced the balance with settlers of Turkish stock. The rest of Thrace was subjected to the same treatment, and as most of its population was transferred to Anatolia, Turkish

settlers came pouring in. The Ottoman tide seemed irresistible, and the mood in the capital was one of gloomy pessimism. “Turkish expansion …” one of them wrote, “is like the sea … it never has peace, but always rolls.”

*

Emperors and diplomats left for Europe to beg for help, but only the pope was interested, and the price for his aid was always the same. The eastern and the western churches must be joined, and the Orthodox must place themselves beneath the authority of Rome. This had already been proposed several times in the past, but always the people of Constantinople had disgustedly rejected it. John V, however, was desperate enough to attempt it again. In 1369, he knelt solemnly on the steps of Saint Peter’s, accepted the supremacy of the pope, and formally converted to Catholicism.

The emperor’s submission was a personal act that had no binding power on anyone else, and the only thing it accomplished was to embarrass John in the eyes of his subjects. The empire may have been distinctly shabby, but Byzantine dignity would never tolerate a willful submission to the hated Latin rite whose crusaders had so recently stained the streets of Constantinople with blood. The westerners had chased the Byzantines from their homes, murdered their families, and ruined their beautiful city. Even if the empire was now plainly doomed, asking its citizens to submit in their faith as well was too much. As far as they were concerned, no aid was worth that cost.

Despite John’s conversion, the promised help from the West never arrived, but the Orthodox power of Serbia responded to the empire’s plight. Marching down into Macedonia, they met the Ottoman army on the banks of the Maritsa River. The Turkish emir Murad—now calling himself sultan—won an overwhelming victory and forced Macedonia’s squabbling princes to become his vassals. Determined to crush the Orthodox spirit, Murad swept into Dalmatia and Bulgaria, sacking their major cities and reducing their princes to

vassalage. A coalition of princes led by the heroic Serbian Stefan Lazar managed to keep the Ottoman advance from entering Bosnia, but in 1389, at the terrible battle of Kosovo, Tsar Lazar was killed and the last vestige of Serbian power was irretrievably broken. The only consolation for the people of the Balkans—whose fate was now sealed—was that Murad didn’t survive the battle. A Serbian soldier feigning desertion was brought before the sultan and managed to plunge a sword into his stomach before being hacked apart by the sultan’s guards.