Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal (61 page)

Read Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal Online

Authors: Jon Wiederhorn

Atreyu breaks “The Curse,” becomes metalcore darlings.

Photograph by Jeremy Saffer.

Meeting of the minds: Alice In Chains bassist Mike Inez and guitarist Jerry Cantrell pose with metal legends Ronnie James Dio and Rob Halford.

Photograph by Stephanie Cabral.

Mastodon’s Brent Hinds rocks the New York crowd at Terminal 5.

Photograph by Jon Wiederhorn.

Modern metal offers something for everybody:

(left to right)

Trivium’s Matt Heafy, Machine Head’s Robb Flynn, Slipknot’s Joey Jordison, Fear Factory’s Dino Cazares.

Photograph by Stephanie Cabral.

Late Slipknot cofounder, songwriter, and bassist Paul Gray.

Photograph by Kevin Hodapp.

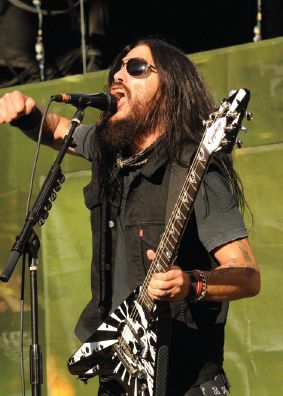

Machine Head front man Robb Flynn clenching the fist of dissent.

Photograph by Stephanie Cabral.

Avenged Sevenfold’s late drummer, Jimmy “The Rev” Sullivan.

Photograph by Stephanie Cabral.

Faith No More backstage at

RIP

magazine party with Ozzy Osbourne and Metallica’s James Hetfield

. Photograph by Nick Charles.

HIGH-TECH HATE: INDUSTRIAL, 1980–1997

T

he descriptors of some subgenres of metal, such as “death” and “black metal,” are nebulous at best. But the word

industrial

conjures up vivid imagery of the music and lyrics it designates: the filth of coal mines, the unrelenting whirr of a sawmill, and, especially, the buzz and grind of automotive factories. Before industrial metal morphed into industrial dance music, its sound was indeed rooted in the sounds of the factory. The term stems from the name of the pioneering band Throbbing Gristle’s label: Industrial Records. Emerging from Kingston upon Hull, England, in 1976, Throbbing Gristle strove to emulate the clatter and clamor of industrial machinery by combining performance art with primitive electronic beats and analog samples. Like-minded artists—Sheffield, England’s Cabaret Voltaire, Sydney, Australia’s SPK, and others—took a similar path to sonic annihilation. Then in 1980, West Germany’s Einstürzende Neubauten emerged with a more percussive style of music that took a fairly literal approach to the term

industrial

, combining actual machinery—including jackhammers, barrels, and chainsaws—with harsh Teutonic vocals. The next wave of industrial bands, including Skinny Puppy (started in Vancouver, Canada, in 1982) and KMFDM (launched in West Germany as a performance art project in 1984), incorporated Neubauten’s dissonant assault with a variety of keyboard melodies and dance beats. (KMFDM was originally called Kein Mehrheit für die Mitleid, which translates as “No pity for the majority”; the acronym was not short for Kill Mother Fucking Depeche Mode, as was widely believed.) As industrial became more structured and technology advanced, bands added distorted electric guitars and caustic samples, making the sound more conventionally metallic.

TRENT REZNOR (Nine Inch Nails):

I don’t mind the term [

industrial

] applied to us, but I think the reason people cringe is what it connotes—Throbbing Gristle, Test Department—bands Nine Inch Nails have very little in common with. What is industrial, then? I’d basically define it as dance music that’s a bit harder, a bit tougher, definitely with a drum machine and maybe some distorted vocals.

ADAM GROSSMAN (Skrew):

When I think of early industrial bands, I picture that guy Dieter from “Sprockets” on

Saturday Night Live

. There was this whole kind of intellectual philosophical based thing that was underground and elitist.

BILL LEEB (Front Line Assembly):

To me, industrial music is six guys onstage with shaved heads, pounding viciously on metal drums. They have sheep’s heads and blood and power drills. There’s a film of an autopsy playing in the background, and there are no effects, no tapes, or samples, or anything.

SASCHA KONIETZKO (KMFDM):

We did an early KMFDM show in Paris and we had a fire-eater onstage, and we would blow up TV sets and bang on sheet metal and air conditioner ducts. We had twenty people onstage, and everybody wore funky outfits. There was fake blood and we were shooting animal intestines around the stage. We’ve changed a lot since then.

BRANDON GEIST (editor in chief,

Revolver

magazine):

At one point, mixing dance music with metal was about as taboo as you could get. It was one thing for metal and punk to start cross-pollinating, because those seem like natural bedfellows. But it took real balls for a metal band to start collaborating with an electronic dance music producer or start making dancey metal.

The most successful artists to create hybrids of metal and industrial are Ministry, Nine Inch Nails, and Marilyn Manson. But the first band to incorporate tangible elements of industrial and metal in their music was London’s Killing Joke. The band formed in 1979 and blended rigid, repetitive riffs, regimental drumming, and aching vocals with strident keyboards and sound effects.

JAZ COLEMAN (Killing Joke):

When we started Killing Joke, we looked to all the outcast philosophers, guys like Nietzsche, Spinoza, and Aleister Crowley, for inspiration. At the time, we were all very cynical about punk. We would listen to dance music and seventies disco music and heavy, dark reggae. Of course, we liked a lot of high-energy music like AC/DC, and it was there that our tradition started.

TONY FLETCHER (journalist):

[Killing Joke] was stark, dark, minimal, confrontational, loud, and not a little violent. And that was just their reputation as interviewees. But there was something truly fascinating about Killing Joke’s apocalyptic vision, and their arrival on the London scene upon the dawn of the eighties was impossible to ignore.

JAZ COLEMAN:

One time in 1981, we had two thousand people at a concert and they were all fighting. It was like the music was a soundtrack to the violence. That’s when I questioned whether I was part of the problem or the solution.

TOMMY VICTOR (Prong, Ministry):

To me, [Killing Joke’s 1980] song “Change” [from their second album,

What’s This For . . . !

] started the whole danceable metal thing, which, eventually, we really used for [our biggest single,] “Snap Your Fingers, Snap Your Neck.”

JAZ COLEMAN:

One of the funny things about Killing Joke was we were intense and things could get violent, but we weren’t one of these self-destructive bands. We’d have gallons of tea and the occasional reefer, but we never drank. Our first gig in America was in 1981 at the Rock Lounge [in New York City]. [Ronald] Reagan had just gotten into office. We were backstage, and this junkie guy came up to [drummer] Big Paul [Ferguson] and said, “Hey man, can I use your belt?” This guy was gonna jack up. Paul took off his belt and started whacking him with it. The guy yelped like a dog and ran out of the dressing room, and the promoter came in and said, “You don’t know what you’ve done. That was Johnny Thunders [late guitarist for the New York Dolls].”