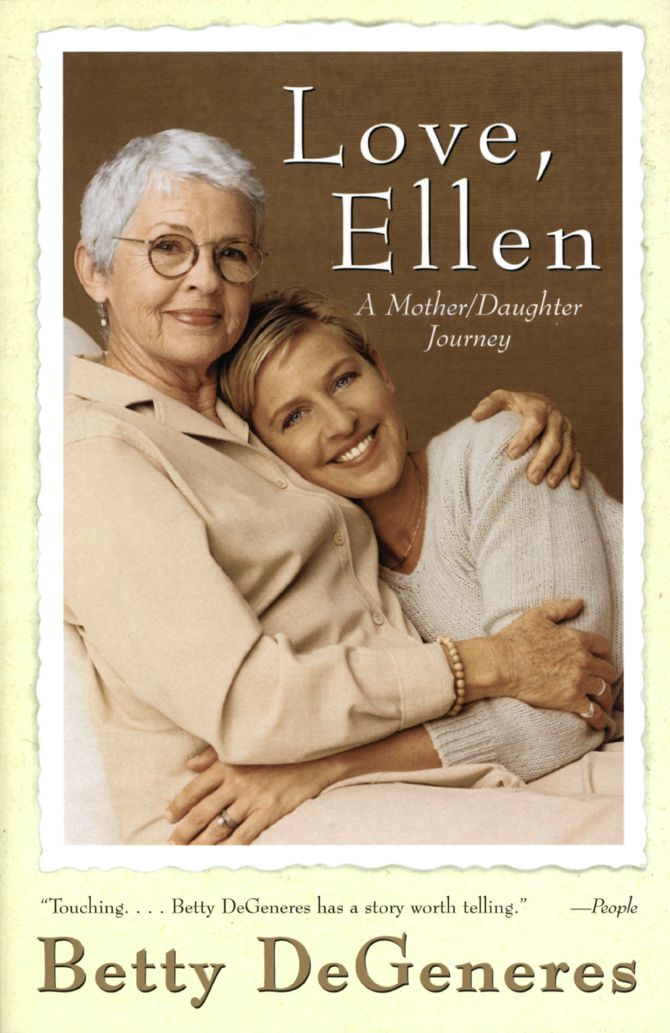

Love, Ellen: A Mother/Daughter Journey

Read Love, Ellen: A Mother/Daughter Journey Online

Authors: Betty DeGeneres

To my kids: Vance, Ellen, and Anne.

And to all those whose parents have rejected them.

I love you all.

M

IM

E

ICHLER-

R

IVAS

. I love Mim Eichler-Rivas. I thank her for her powers of organization and structure—for inspiring, prodding, and pushing me. Thanks to Rob Weisbach for his guidance and encouragement and thanks to the whole terrific team at Rob Weisbach Books. Thanks to Elizabeth Birch and the Human Rights Campaign for filling my life with love and giving me the job I think I was meant to do. Being the first non-gay spokesperson for the National Coming Out Project has been the most fulfilling work I could ever imagine. Thanks to David Smith for keeping me on schedule, telling me where I’m going and when, and being my number-one cheer-leader. David, and everyone at HRC, gave me confidence that I could do this work long before I should have been confident. Thanks to Bob Witeck and Wes Combs for their inspired speech writing. Thanks to Jan Sonnenmair, photographer extraordinaire. Thanks to Bob Barnett and Jacqueline Davies for their expertise. Thanks to all of you, my dear new friends, for telling me your stories. And thanks to all of you, whose names I will never know, who shared your feelings of hope and despair with me.

Thanks to my sister Helen, my son, Vance, and my daughters, Ellen and Anne. Thanks for your excellent advice and your love. I couldn’t live without them.

Thanks to all in our family, who have always been supportive and proud. And last, but certainly not least, thanks to all my friends across the country—both old and new. You know who you are. I love you all.

Finally, I must acknowledge Matthew Shepard. His tragic death affects every human being. His suffering leaves us all diminished—and we must never forget him.

Contents

Prologue: Coming Out, the First Time

1. The Importance of Being Different

5. The Importance of Being Honest

6. I Love You, Mom: I Love You. El

Part III: April 30, 1997, to the Present

Lagniappe—A Little Something Extra

Go without hate, but not without rage. Heal the world.

—P

AUL

M

ONETTE

P

ASS

C

HRISTIAN

, M

ISSISSIPPI

1978

T

HREE WORDS, SPOKEN

two decades ago by my daughter Ellen at the age of twenty, changed my life forever. In an instant, her bombshell shattered many of my long-held beliefs about who she was, who I was, and about life itself.

Nothing in the months, days, hours, or minutes leading up to that moment could have prepared me for what she would tell me that day. Twenty minutes earlier, just before Ellen suggested we go for a walk on the beach, we had been enjoying a large, relatively uneventful family gathering in Pass Christian on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

This small beach community is an hour’s drive from New Orleans, Louisiana, where I grew up and raised my two kids, Vance and Ellen. It is where my oldest sister, Helen, lived for many years with her family in their lovely, comfortable home on West Beach Boulevard, facing the water. The house, set far back from the boulevard, has a wide screened porch and a large front yard full of shade trees. Inside, the spacious living room has a well-used fireplace and the large dining room opens onto a cozy sunroom.

From the time our kids were small, Helen’s was an ideal place to gather for holidays and other happy occasions. At Thanksgiving, Christmas, summer picnic reunions, and other celebrations our number would swell, with grandparents, cousins, uncles, aunts, nieces, nephews, and a few neighbors and friends. Lots of us! Yet we never felt that we were intruding or had overstayed our welcome.

For those winter holiday feasts, the dining room always managed to accommodate us all; afterward we’d share long, leisurely hours by the fire. In warm weather, we always ate outdoors, at picnic tables in the front yard. We have home movies of all the children swinging on a rope tied to a tall tree branch. They’d stand on a picnic table to catch it as it swung by.

To escape the heat we could sit on the screened porch or relax in a hammock. Of course, when it was really hot, every-one headed for the beach—to sit on the sand or swim or go sailing in the Sunfish.

The house on West Beach Boulevard has a wealth of cherished memories for me. Like old photographs, many of those happy moments have faded in my mind with the passage of time, the different years blurring one into the next. And yet, I can vividly recall this particular life-changing visit, which came at the end of the summer of 1978.

At the time, I was living eight hours away in Atlanta, Texas, with my then husband, whom I had married after divorcing Vance and Ellen’s father several years earlier. Vance, the older of my two kids, couldn’t be with us; he was in Yuma, Arizona, finishing up his two years of service in the Marines, after already having started to make a name for himself in comedy writing and rock music. Ellen, however, was able to make it. She was living just an hour away in New Orleans at her dad’s house, so she rode over to Helen’s with us.

That meant a chance to do some catching up. Living so far away from each other was hard on both of us. We were always extremely close and missed the luxury of being together on a daily basis. In those days, Ellen was still struggling to find a direction for herself. After graduating from high school, she had tried college for all of a month, only to conclude that wasn’t for her. She then embarked on what would ultimately become one of the longest lists of jobs known to humankind—everything from vacuum cleaner salesperson to oyster shucker—before finding her true calling. But even then, Ellen had a knack for describing even the most mundane details of her struggles and making them sound hilarious or dramatic. That weekend was no exception. So I had no reason to suspect that anything was different or out of the ordinary about Ellen.

Nor did it seem unusual when, after we all finished dinner late that afternoon, El said to me, “Let’s go out for one more walk on the beach.’’

When we crossed West Beach Boulevard and walked down the steps of the seawall, I began to sense that she had something on her mind. Probably, I imagined, it was her latest job, or maybe a new boyfriend. But we weren’t really talking much as we walked across the broad, sandy beach down to the hard-packed sand by the water’s edge. The cool salty breeze felt wonderful as we walked along and my daughter, at my side, was a pretty sight. With her straight blond hair and her sparkling blue eyes, she really was the essence of the girl next door. What a treat to be together, walking along quietly.

But suddenly Ellen stopped, and I turned back to see why. She had tears in her eyes, which alarmed me. As I walked toward her in concern, she began to cry, and it was then that she sobbed with a depth of emotion I will never forget and spoke those three words: “Mom, I’m gay.”

In my mind, everything stopped. This was the biggest shock of my life and the last thing I had ever expected to hear. Still reeling, I reached out to comfort her. She was upset and crying, so I did the most natural thing a mother would do—I took her into my arms and hugged her. No mother wants to see her child in pain.

Reassuring her that I loved her was my first priority. But it would take time for the words she had just spoken to sink in. There was no way I could comprehend or process or accept this news immediately. My shock was coupled with disbelief. As close as we were, this was not the Ellen I knew. On the other hand, if we had been living in the same city and had been in more constant touch, I probably would have had some clues.

It was my turn to talk, but I didn’t know what to say. A hundred different thoughts and emotions were racing through me. In my mind I was frantically reaching, searching for any question, any argument, that would bring her back to her senses—back to being the lovely, young heterosexual daughter she always had been.

Heterosexual daughter.

That thought gripped me. It is such a natural assumption that we don’t even have to consider the word. It isn’t even in our usual vocabulary. We just are. But now, I had to consider another word that wasn’t in my usual vocabulary—homosexual.

My homosexual daughter

—just thinking those strange words brought on a new wave of emotion that I recognized as fear. I feared for Ellen’s well-being, given society’s prejudiced and negative attitudes. Though I had almost no exposure to gay people at all, I knew the derogatory names used for them, and I didn’t want my daughter called those names.

And, then, of all things, as I was hugging Ellen and waiting for her tears to subside, the most frivolous but upsetting thought came out of nowhere. Now, I sadly realized, El’s engagement picture would never appear in the New Orleans newspaper.

In those days, whenever I was home for a visit, I’d always look at the engagement announcements of young women in the

Times Picayune

, and I would often recognize the maiden name of the mother—a friend from high school or college. I had always fantasized about seeing Ellen’s picture there and about her marrying some fine young man and about myself as the proud mother of the bride.

In retrospect, it’s ironic that although Ellen never had an engagement picture in my hometown paper, in years to come she would be a featured celebrity not only in the

Picayune

but on the covers of magazines and papers all over the world. At that time, however, such fame was far beyond my fantasies. I felt as if a dream had been shattered.

Only later would I understand that my disappointment was not for Ellen. It was for me. I was the one whose marriages hadn’t worked out according to expectations. Why on earth should she have to fulfill my dreams? Why not love her and support her as she fulfilled her own?

When I finally found my voice, I asked, “Are you sure?” The question hung in the air. It sounded judgmental. I softened it, saying, “I mean, couldn’t this just be a phase?”

Ellen almost smiled. “No, Mother,” she said. “It’s not a phase. I’m sure.”

More questions followed: “How do you know?” “How long have you known?”

Ellen tried to answer truthfully. “I think I’ve always known, but I didn’t know what to call it. Now I do. I’m gay, Mom.”

It was getting dark, and when we started back to the house, she reminded me of a movie we had seen together a couple of years earlier. As I recall, it was

Valley of the Dolls

, or something like that. Ellen said, “You know that scene when the two girls were touching and hugging, I thought that was gross. I’d never seen anything like that before. But then it happened to me, and it wasn’t gross, Mom.”

She told me more about her first experience. She also told me that a friendship formed after her return to New Orleans was more than that. Ellen felt that she was in love.

Even as I tried to understand, I was in a state of denial. “But, Ellen, boys have always liked you, and you’re so popular. You just need to meet the right one.”

She shook her head. “I’ve dated a lot of nice boys. That’s not who I am.” Ellen’s expression was wistful and solemn, yet also relieved—as if a burden had been lifted off her. I was feeling many things at that point, but relief wasn’t one of them.

We walked back into the house. We were not the same mother and daughter who had left thirty minutes before. We looked the same, but we were not. Nobody else knew—not for a while. Now we had a secret.

Every family of a gay person has its own story. This was ours, a story that would develop and unfold in many surprising ways.

I’ve heard that some parents are able to accept this news about their sons or daughters readily, with equanimity, even with happiness. I’m sorry to say that I wasn’t one of them. Like most parents, I went through a process. It took me time to think about this, to sort out what was important, to get past my terrible ignorance and learn about homosexuality. Though somewhat familiar with the myths and fallacies that are all too common, I needed to learn facts. Two of the most important facts I would learn were, first of all, that as a rule people don’t choose to be homosexual; and second, that being gay is normal and healthy. But embracing these truths would take time.

As I grappled with this new information about Ellen, some of what I went through was not unlike the grieving process that follows the death of a loved one—which is also a process of growth. Of course, what was dying wasn’t a loved one, but my own expectations about the way Ellen should be. And in their place, room was being made for the truth, about her and about me.

Though this process was hard and sometimes painful, what matters is that I did recognize it as a process, and I allowed it to take its course. Another important thing is that during this whole time I loved my daughter as much as I ever had, and she loved me. We kept the lines of communication open. This is vital, although not necessarily easy.

A short while after that day on the beach, early in my struggle, I spoke to Ellen on the phone, and more questions came out. Was it something in her upbringing? Maybe, I suggested, it was the kind of people she was hanging around with.

“What do you mean?” Ellen said angrily.

“Well, how well do you know them?” The disapproval in my voice was obvious.

Her tone was hurt as she asked, “What are you so unhappy about?”

“It’s just that I always dreamed of seeing your engagement picture in the paper,” I confessed, the words spilling out. “It worries me that you won’t have a man to provide for you and look after you. And what about having your own children?”

The conversation was going downhill fast, and we got off the phone hurriedly.

A few days later, I received this letter from Ellen:

Dear Mother,

I’ve had a horrible day since I talked to you on the phone! What you said upset me very much. … I’m really sorry if I’m not the daughter you hoped I’d be—that I don’t have my engagement picture in the paper and am 3 months’ pregnant! And I’m not being sarcastic either! And I know this must hurt you a lot—and it’s hard for you to accept.

But think about me too! I love you so much—you know how much you mean to me. When you’re upset about something, I feel just as much pain. Don’t you understand I care so much for you—but I can’t change my feelings.

I am in love—I didn’t force it—it just happened and I’m not about to break away from the only thing in my life that keeps me going just for you or society or anything. I’m very happy and I’m sorry you can’t approve—I know you can’t understand—you probably never will. No one can ever understand anything until they’ve experienced it themselves. You were brought up totally different—lifestyle, generation, surroundings, people, environment, etc. …

I just want you to know you’re not the only one who gets upset when we don’t see things eye to eye. All I ask is that you try to believe me—I’m not sick. I’m not crazy. It just happened, and my friends are not sick—they’re normal, healthy, good-looking, well-dressed, polite, young adults who also strayed from society’s rule. I just wish you could meet them and see how your image of “them” is so wrong. …

I hope we have a lot of time alone together—we really need to talk.

Love you much,

Ellen

She was absolutely right: we did need to spend time talking. And so we did. As we did, I was able to remind her that I accepted and loved her unconditionally. Maybe I would never totally understand, I admitted, but I was going to do everything in my power to try.

Over the next years, we corresponded, we wrote poems to each other, we talked on the phone, we laughed, and we cried. We never lost close contact. “Love, Ellen,” or some form thereof, was how she signed off every time she ended a letter or said good-bye after a talk. That love was never taken for granted, on either side.

Ever so slowly, as I met her friends and her partners, I relaxed, seeing how very happy she was—and is. Along the way, I learned many lessons not only about what it means to be gay but about what it means to be human, lessons about love and courage and honesty.

This has been an amazing journey, the journey which began so shockingly for me that day in 1978 on the beach in Pass Christian. The twists and turns in our road have led to many surprises, including Ellen’s professional success in movies and as the star of her own television series.