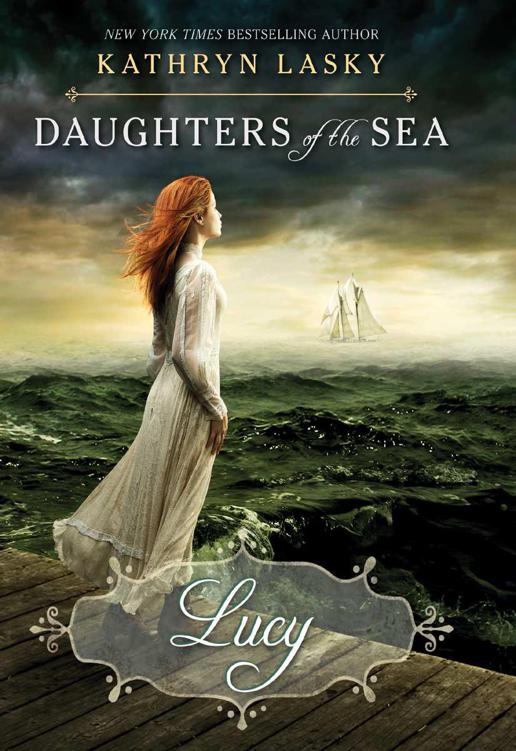

Lucy: Daughters of the Sea #3

Read Lucy: Daughters of the Sea #3 Online

Authors: Kathryn Lasky

M

ARJORIE

S

NOW

,

wife of the Reverend Stephen Snow, peered into the bedroom of her daughter, Lucy. In a corner on a table was the dollhouse that Aunt Prissy had given Lucy for her ninth birthday — a perfect replica of Prissy’s estate, White Oaks. What a lovely house it had been, complete with the most charming decorations; even the wallpaper had been scaled down to dollhouse dimensions. And what had that peculiar little girl done but painted over it! A seascape, of all things. Not that she had made a mess of it. Hardly. Lucy had always exhibited an artistic bent far beyond her years. It was a lovely scene. But when Aunt Prissy came to visit, Marjorie could see that she was upset by the alterations to the house. She tried to cover her agitation by murmuring soft little exclamations, the verbal equivalent of the weak tea one might serve a patient convalescing from a stomach ailment.

“My … my … what changes you have made. Yes, you have quite an eye for detail…. And what happened to the French-style armoire? Oh, yes, there it is. You’ve painted it, too, I see. Sea anemones. And who might live here, Lucy? A nice little family, I imagine.”

And then a most peculiar conversation ensued, much to Marjorie’s consternation.

“Yes, Aunt Prissy. The Begats,” Lucy answered softly, and a slight blush crept across her cheeks.

“The who? The Beggars?”

“No, the Begats. B-e-g-a-t-s.” Lucy spelled the word out.

Her aunt Prissy complimented her on her spelling, then commented, “That’s quite interesting, Lucy dear. Now, where did you ever come up with that name?”

Lucy’s green eyes widened. “The Bible, Matthew, chapter one, verse one through seventeen.”

“Oh,

those

Begats,” Aunt Prissy exclaimed as if it were a distinguished family that she had somehow overlooked. “How very curious!”

“Well, her father is a minister, Priscilla,” Marjorie interjected. “She does know the Bible. Only normal.”

“Yes, of course. That must explain it.”

The word

must

suggested that it had better explain it because Priscilla Bancroft Devries felt there was precious little else normal about this child.

Despite her peculiarities, Lucy was an obedient child. However, if there was one thing that Marjorie wished she could change, it was her daughter’s tendency toward withdrawal. And of course the limp caused by her slightly turned foot. “Not a clubfoot,” her mother was quick to assure everyone when they saw the infant for the first time. “Doctor Webb says it’s ever so slight, and with the proper shoes, it is entirely correctable.”

Lucy of course hated the proper shoes. She complained about them constantly and, when she was at home, would often scamper about in her stocking feet. The limp had decreased, but it had not disappeared entirely, and Marjorie felt that this was what inhibited her daughter in society. She disliked dancing for, she said, the shoes made her clumsy. And she would often stay rooted to one spot at a party, preferably behind the foliage of a large potted palm, rather than mingle with the guests. Lucy definitely was not a “mingler.” In Marjorie Snow’s mind, mingling was somewhere between an art form and a kind of elegant athleticism. She praised an aptitude for mingling as one might revere a good circulatory system. Marjorie hoped that Lucy would outgrow her shyness, but as she entered her teens, Lucy only blossomed into a wallflower.

This was most evident at the tea dances given at the Excelsior Gardens on Park Avenue. The Excelsior was a private club to which the Snows did not belong but were frequently invited, owing to the reverend’s position as minister of St. Luke’s.

With the possible exception of Trinity on Fifth Avenue, there was not a finer church than St. Luke’s, which had produced two of the last three Episcopal bishops of the diocese of New York. And if Marjorie had her way, Stephen would succeed that doddering old fool who was the present bishop. That was when the Snows would truly get their due, part of which would include becoming members of the Excelsior Club. Stephen had promised. “

The office demands it

,” he had said. One simply could not become the bishop of New York without being invited to join the leading clubs. And the office would also demand that Lucy, dear Lucy, become a bit more outgoing.

Outgoing

was a favorite word of Marjorie Snow’s. Her recurring plea to Lucy was that she try a bit harder in “the social department” or sometimes “social area.”

At least she had convinced Lucy to go to the afternoon reception the Ogmonts were giving for their niece, who had just arrived from Paris. The Ogmonts, who perched on the loftiest pinnacle of New York society, were related to the Drexels, and this was a coveted invitation for the young set. A last dip into society until people scattered to the summer watering holes in a few weeks.

And now the reverend had come home with wonderful news that they, too, would be joining the summer migration, and Marjorie had no one to tell it to. She could write Prissy, of course, or possibly telegram her, but that cost. They had a telephone, thanks to the church, but Marjorie had no idea how to make a long-distance call all the way to Baltimore. Oh, she wanted to tell somebody! If only Lucy knew that her father had been asked to be the summer minister in Bar Harbor, Maine, she would have had so much to talk about at the reception.