Machine Of Death (21 page)

Authors: David Malki,Mathew Bennardo,Ryan North

Tags: #Humor, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Horror, #Adult, #Dystopia, #Collections, #Philosophy

When they called me I felt a little nervous. Like, everyone knows they’re going to die, but it’s still a wobbly feeling to find out exactly how. My knees felt like they wanted to bend the wrong way, and I almost tripped getting out of my chair. I grabbed my bag and waved to Kells. She mouthed “old age!” at me and gave me a thumbs-up. I smiled back.

I went into the room and sat down, and the counselor made me go through the whole routine. I had to tell him my social, twice. I had to do the iris-scanner, both eyes. I had to show him the waiver from my parents that allowed him to tell me without them present, and I had to sign a form allowing him to tell me, period, and releasing the test people from liability. Then I had to do the breathalyzer; a couple of years ago kids would show up wasted or high for their tests, so now you can’t get the results unless you’re sober.

Finally he brought out my ticket. It wasn’t in an envelope or anything, it was just the top one in his folder. The folder was black, which I thought was kind of weird. Like, why make the folder black? He was dressed in just regular clothes, tan pants and a blue shirt, no tie or anything, so the black folder just seemed kinda pretentious.

“You have a slightly unusual result,” he said. That wasn’t good. Unusual meant stuff like mauled by a bear, or electric-mixer accident, or choked on a pickle. Stupid stuff. Not dramatic or cool.

“Let me see.” I really didn’t want to wait. He pushed the ticket over to me.

In block letters, it said

NOT

WAVING

BUT

DROWNING

.

The man said, “It’s a line from a poem.” He held his pen like he didn’t know what it was for.

“But it still means I’m drowning, right? It’s not so bad.”

“We’d like you to have the test retaken. It’s unusual to get something like this. Something so…allusive.”

I looked at him. He hadn’t done a good job shaving that morning; it looked like he used a real razor and not a depilatory laser. Maybe his ticket said he’d be killed by a laser?

“I don’t know. I like this one. What if it changed to something worse?”

“That doesn’t really happen. They don’t change. Sometimes they get more specific—we think yours would get more specific.”

“I think I’m good with vague, thanks. Vague and poetic is okay with me.”

“Are you sure? You could retake now…” I noticed that he had a test kit, too, next to his chair.

“Nah. I’m okay.” I put my ticket in my bag, careful not to fold it. Some people framed theirs, and kept it somewhere safe, especially if it was a cool one, like “saving a child.” Mine was totally frameable.

“If you change your mind, here’s a number to call.” He beamed a number to my phone from his pen. “And we’d like your permission to keep a tracer on you, so that our department will be alerted when you die.”

Wow—I was important enough to have a tracer? That was also cool. I couldn’t decide if I’d tell anyone about the ticket, but I could definitely tell people I had a tracer.

“Sure, okay.” He pushed another form to me.

“We have to let you think about this one for twenty-four hours, and your parents have to sign it, too. I have to disclose to you that tracer information is subpoenable, which means that if you are accused of a crime the data from the tracer can be used by the prosecution and the defense. It cannot be requested for civil matters in this state, but it can in New York, California, New Mexico, and Mississippi. You can drop off the form in homeroom tomorrow, or you can ping us if you sign it earlier and someone will come by to get it from you and your parents.”

He stood up, so I got up, too. He shook my hand. “I think you are a remarkable young woman,” he said, like he didn’t say that to everyone. “Please use this knowledge to focus and direct your life, and to live while you can.” Then he recited the machine motto,

Dum vivimus vivamus.

Although nobody really knows Latin anymore, everyone knows that bit. It means “while we live, let us live.”

On my way home, Kells texted me. “

OLD

AGE

OMG

YAY!!!” was her whole text, so I just sent back a smiley and an “IM OK” and another smiley. Mine really wasn’t something you could text. I was glad for her, though. I bet she was going to be the great-grandma-in-the-room-full-of-flowers kind of old age dying.

My folks were home, and I think they had been crying. It’s hard to think of people you love dying. Like they thought if they didn’t know, I’d live forever or something. My dad gave me a big hug and kind of sniffled, before I even showed him the ticket, which was weird.

I didn’t really know what to say about the ticket, so I just pulled it out and showed it to them. “The guy said it was from a poem.” My folks looked a little shocked, but then my mom just googled up the poem on the living room screen. We just stood there and read it, and clicked through to read about the poet. It was by somebody named Stevie Smith, who I first thought was a guy but who turned out to be a woman. The poem was kind of famous, but pretty old, older than my parents. Stevie died of a brain tumor, which was as close as you could get back then to knowing for sure how you were going to die. Not a lot of people survived brain tumors. I kind of liked that she died that way. Not that she died, of course, but that she probably knew.

My grandpa, for all he talks about how he hates the machine, came in while we were clicking around. My dad hates that he just walks in, but my grandpa always forgets to use the bell, or even to set his phone to ping us when he’s close, and of course the house is set to let him in. My dad didn’t notice him until he was right there, close, and then he said “Jesus, Pops!” in a kind of shaky voice.

Grandpa didn’t even ask, he just looked at my ticket. “Ho ho!” he said. (He’s the only person outside of the vids who ever says “ho ho!” in that old-timey way, instead of in the “ho ho ho” Santa way.) “Now that’s a poetic death. I could almost warm up to a machine that spits that out.”

Anyway, that’s when my mom and dad and grandpa started arguing about whether it was good or awful, and my dad started in again telling my grandpa he should get tested, so I kind of sneaked away and went up to my room. I didn’t know myself, but I kind of liked the not-knowing. The fact that it was a line of a poem: cool. The fact that I could get a tracer: cool. Drowning: not so bad. I’d heard it was peaceful, and I really hate swimming anyway (it messes up my hair) so that was good to have an excuse not to swim.

I pulled up the poem again and made it the background on my screen. I think I’ll leave it there for a little while.

Story by Erin McKean

Illustration by Carly Monardo

PREPARED

BLOWFISH

ISHIKAWA

TSUENO

AND

HIS

JUNIOR

,

KIMU

MAKOTO

,

SAT

HUNCHED

IN

THEIR

CHAIRS

,

PANTING

IN

THE

HUMID

,

DARK

RECEPTION

OFFICE

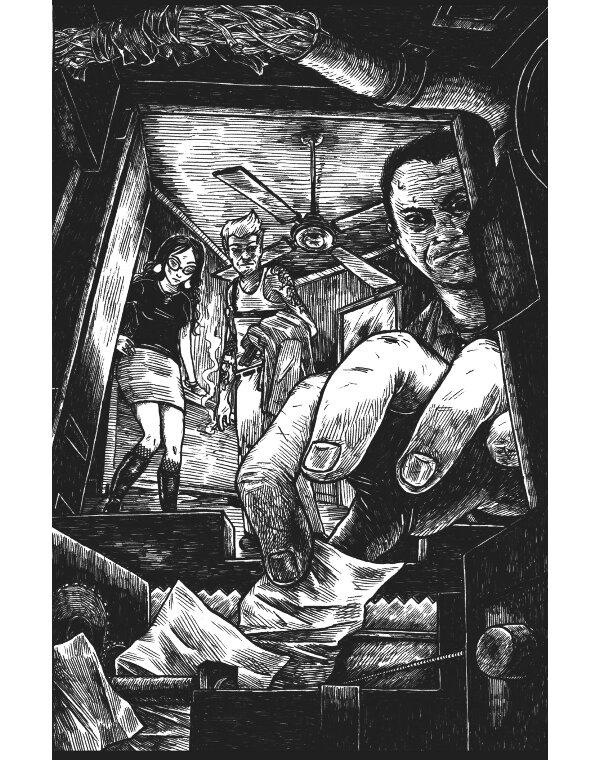

. Kimu removed his suit jacket and plaintively massage-punched himself in the arms, while Tsueno just cracked his neck and upper back with a slight tilt of his head, sat back, and breathed deeply. The air in the little upstairs room was faintly curdled by the persistent scents of ancient sweat and menthol cigarettes. The ceiling fan did nothing to banish those odors, nor to dissipate the heat in the room that had built up all day.

Relaxing, Tsueno slipped off his shoes, and looked down at them. He noticed a wide smear of gooey blood on the left one. Shaking his head, he tugged a handkerchief out of his pants pocket and wiped it off. As he was leaning forward, he noticed that there were bits of brain and clotted blood spattered on his pant leg, too. He cussed to himself:

stupid bastards.

Why couldn’t they have just handed the damned machine over? It would have saved him a trip to the dry cleaners.

As he finished wiping his shoe and picking bits off his pant leg, and crumpled the handkerchief in one hand, Ito’s woman Yukie entered the room through the back door. Yukie was not Ito’s wife, but his 22-year-old lover. She was young enough to be his daughter, and looked sexy as ever: miniskirt, skintight black t-shirt, big amber-tinted sunglasses, all kinds of jewelry, heavy makeup. She was carrying a tray of some kind, though it was too dark to see what was on it from across the room. She shut the door behind her with a high-heeled foot, closing off the inner sanctum of the mens’ boss, “Father” Ito.

Yukie walked right up to the machine, bent forward a little, and gave it a close look.

“Heavy,” she mumbled.

Tsueno nodded, shoving the bloodied handkerchief into his pocket. Kimu nodded, too, and smiled toothily at her. It was indeed a heavy machine, about the size of a small photocopier but apparently densely solid inside. Carrying it up three flights of stairs at a leisurely pace would have been bad enough, but hurrying the thing up to Ito’s office had just about killed Tsueno. Once again, he regretted that the smaller models Kimu had found online had not been released in Japan before the machines had been banned. Yukie smiled as she looked at them, still trying to catch their breaths, and then turned back to the machine. She started sounding out some of the English labels on the buttons.

Tsueno turned and saw Kimu staring at Yukie’s backside, and sighed. Damn undisciplined

Zainichi

. Yes, he thought to himself as his eyes brushed her long bare legs, her body was perfect—not that his own wife’s was anything to sneeze at—but you don’t stare at your

Oyabun

‘s woman like that. He’d worked with Korean-blooded Japanese before, and had been reluctant to take Kimu on because of his experience with crap like this. Tsueno wondered just how foolish Kimu was. The guy was young, and fit. There were thousands of girls in Fukuoka alone who’d sleep with him, many of them almost as sexy as Yukie. Was the chip on his shoulder

that

big? Tsueno wondered whether Kimu’s father hadn’t perhaps been killed for the same exact behaviour, leaving his son orphaned over a momentary leer.

“Here,” Yukie said, turning and setting her tray out on the table. On it were some paper cups and a few glistening bottles of iced green tea.

“

Arigato

gozaimasu

,” Tsueno said, conspicuously polite without even thinking about it. Yukie was the boss’s woman. The last man who’d spoken to her too familiarly had, rather famously, been chopped up and fed to one of Ito’s pet crocodiles. Tsueno reached for one of the bottles. It was ice-cold, and the droplets of condensation on the plastic felt wonderful in his hand, against his forehead as he raised it to his skin to cool himself. He felt like shoving the bottle down his shirt-front. Why the hell hadn’t Ito ever installed an air conditioner in the reception room?

Yukie just smiled, and sat down to wait. She turned her head, and looked at the machine some more.

She doesn’t usually serve drinks, Tsueno observed. She must’ve been sent to fill time. Was their

Oyabun

—their boss—stalling? But why? Ito had always had a predilection for old things: An old sword hung on the wall behind his desk, and he was always reading old novels. Perhaps he was even old-fashioned enough to be terrified of tempting fate, by actually using the Machine of Death? Some kind of Kawabata-type dramatic crap? Tsueno had read a book by that guy. He much preferred manga. Especially vampire manga.

After a few long minutes, Yukie said, almost sang, “It’s very big.” Her voice was high-pitched, melodious. Tsueno quipped silently to himself about how her conviction was very well-practiced on this familiar line.

“Yeah. It’s an older model, ya know,” Kimu said, and retrieved a pack of cigarettes from his shirt pocket. He was slouching noticeably, where Tsueno had sat up a little.

Tsueno wrinkled his nose, scratched it with the tip of a finger, looked at Kimu and Yukie.

“Do the older ones work as well?” she asked, mellifluous.

“Sure, they’re all the same inside. Like men,” Kimu blurted, with a smirk. “The newer machines are lighter, but there still aren’t many of them around. They’ve been banned.” Kimu flicked his lighter, and lit the cigarette. After a few puffs, he sighed in obvious satisfaction.

She nodded again. Tsueno watched the two of them talking. He felt hungry. He slid his chair toward the wall, away from the other two. He wished softly to himself that she would go back into their

Oyabun

‘s office.

“Does it plug in?” Yukie inquired, suddenly.

“Yes, ma’am,” Kimu said, and winked.

“Where’s the cable?”

Tsueno sat up, alarmed, and looked at the box on the table. He cussed mildly at Kimu. “Hey, where

is

the cable?”

“Probably in the trunk,” Kimu said with a shrug.

“Go get it,” Tsueno said, suddenly speaking with all the authority of a proper

senpai

, an elder whose orders were to be respected without question. “Now.”

A defeated look crossed Kimu’s face, but he nodded and rose to his feet. A bottle of iced green tea in one hand, he left the room. That, at least, Kimu seemed to understand:

senpai

orders, and

kohai

obeys. The relationship between junior and senior was something even a depraved, orphaned

Zainichi

like Kimu understood to the bone.