Machine Of Death (45 page)

Authors: David Malki,Mathew Bennardo,Ryan North

Tags: #Humor, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Horror, #Adult, #Dystopia, #Collections, #Philosophy

At the same time that the streets are opening up, they’re also closing in. The city is a city during the day—people coming and going on business, tourists waltzing through and then back out, leaving snapshots and traveler’s checks in their wake—but at night it becomes a home. Everyone acts a little different—after all, we’re all roommates on a grander scale. This is my home, but it’s yours, too.

Mi casa es su casa. Mi ciudad es su ciudad.

We’re all in this together.

Those smiles to passersby that seem forced in the light become smirks at three in the morning. The raised eyebrow that says, “How was she?” or “I bet you could use a drink, too.” People’s walls start to come down. Masks are for daylight—once dusk hits, it’s the moon’s turf, and she likes us naked, naked, naked, just the way she made us.

Or at least some of us. The poets. The dreamers. The dancers and weavers. Sure, there are children of the sun out there—hardworking proponents of duty and righteousness—but not at night. We are the merrymakers, the children of the moon. And the moon, she takes care of her own.

She was taking care of Ryan as he ran across the bridge, her light following him as he took in the skyline, the radio towers and bedroom windows that lit his way home, offering nothing but asking nothing in return. It was a sight that had taken his breath away the first time, and every subsequent viewing was a chance to return to that original moment—who he was with, what he was doing.

Ryan wasn’t interested in going back tonight, nor home. The globes on the streetlamps glowed soft as he turned down the footpath, hedges forming a tunnel before opening up into the park proper. Here it was dark enough that the moon washed away the colors, leaving only stark whites and grays. And black. Lots of black.

Annie was waiting on the merry-go-round, one foot dragging in the dust. The contrast of blonde hair over heavy black peacoat was enough to fry the rods in his eyes and blind him to more subtle distinctions, but he knew they were there. The tiny triangle where her nose met her lips. The scar on her cheek that made her hate cats. The ears that poked through the sides of her hair in a way that only she found awkward. She stood up, and the diminishing momentum of the merry-go-round carried her up to him, then stopped.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” she replied.

They stood awkwardly for a moment, then she sat and he followed, close but separated by the toy’s dully reflective steel rail.

“How was the hospital?” she asked.

“Not too bad. Long.” He sighed and pulled his jacket closer around him. She knew it was a loaded question—it was every time. How could he explain that working in the ER was simultaneously exhilarating and crushing? That in any given day, he worked miracles and failed miserably, complete strangers giving up and expiring beneath his hands? He couldn’t, and once upon a time he’d told her so. So now she asked how his day was, and he said fine, and both of them knew that the exchange was one of affection, not information.

The machine didn’t make his job any easier, either. You’d think it would warn people, let them know what was coming, or at the very least aid in diagnosis and emergency room triage, but somehow it rarely did. Every day he saw people making good on their little certificates, and every day it took all but a select few by surprise. Some were straightforward—the middle-aged man with the steering column in his chest and

DRUNK

DRIVER

on the laminated slip in his pocket, or the kid who quit breathing on Sloppy Joe Day and hadn’t yet been informed by his parents that

CHOKE

ON

CAFETERIA

FOOD

was the last entry in his abbreviated biography. Others were more complex—the third-degree burn victim who tried to cheat death by never smoking a pack in his life, only to be done in by the upstairs neighbor who fell asleep with a lit cigarette near the drapes. Or the woman with

SAILBOAT

ACCIDENT

in her wallet, crushed by a towed yacht in a five-car pileup. The list went on. One way or another, things always worked out in the end.

Though the residents and long-time nurses did their best to combat complacency—after all, you could never know if the heart attack implied on the slip was this one, or another in thirty years—you could still see the knowing look in the doctors’ eyes when someone crashed. If you were lucky, the advance warning made things a little less traumatic for both patient and doctor. More dignified.

Annie pushed off from the ground and the merry-go-round spun hesitantly, their weight throwing it off balance and making it squeal against its steel and rubber fittings. Ryan realized he’d trailed off and snapped back to the present, turning toward her.

“Did you talk to your mom?” he asked.

“Yeah.”

“How did it go?”

“About how we expected.” She reached up with one hand and tucked a lock of severely cropped white-blond hair behind her ear. “She doesn’t really trust it, and has all sorts of philosophical misgivings, but in the end she knows it’s our decision and supports us without question. She’d like us to come out and see the new house whenever we can—she’s trying to hold it back, but I can tell she’s already gearing up to play the doting grandmother. She’s probably already got the shower half-planned. I told her you’re booked solid, but that we might be able to make it out in a month or so. What do you think?”

Ryan grunted noncommittally, feigning reluctance. She shoved his shoulder hard, tipping him off balance.

“Oh, come on,” she said. “You know you love it. You don’t even have to help cook—you just get to read and ride the horses and hang out with William. I’m the one who’s going to have to go visit eighty-year-old great-aunts and listen to stories about people who died in 1967.” She stood and grabbed his hand. “Come on, let’s go sit on the swings.”

Ryan stood and let her pull him along. In the dark, her tiny hands glowed against her sleeves, and he marveled at the boundless energy contained in something so small and delicate.

The park was nothing extravagant—a gravel-covered box edged with trees on one side, with the merry-go-round, a few big climbing toys, and a swing set. Nothing like the expansive playgrounds both of them had grown up with, but that was the price they paid for living in the city. During the day, every square foot was covered in running, yelling children, offering local mothers a few minutes to read their books on the surrounding benches. But at night it stood empty, save for the occasional drug deal or sleepy hobo.

Annie had exploded into Ryan’s life like a mortar round, with only the faintest whistle to warn him. A smile across a crowded party, and suddenly she was right in front of him, introducing herself with a confidence that made him sweat. The rest of the party had suddenly paled in comparison, fading to a dull buzz, and the two had quietly excused themselves, drifting out into the silent streets.

Something about each of them opened a vein in the other, and the conversation flowed in great torrents, both of them pushing further and faster, daring each other to greater depths of intimacy. In a heartbeat Ryan found himself offering up his deepest secrets, astonished and enraptured by the care with which she picked each one up, examined it carefully from all sides, and then replaced it. They’d walked for hours, finally stopping in this park to rest on the swing set. When they eventually left, he’d gone home alone, but something had changed. It was a new sort of alone, relaxed and refreshed.

He’d invited her out again, and once more they’d walked until they dropped, taking a different path but still ending at the park. He’d repeated the date three times, reluctant to risk changing any variables, before she finally suggested that they might want to try going out to dinner or a movie once in a while. The fact that she said it while lying in his bed, hair tousled and one pink-tipped breast peeking out from beneath the threadbare cotton sheets, had taken any sting out of her words. They’d built a life together, but the park had always maintained a special place in their relationship. It was there that he’d asked her to marry him—not the most creative choice, but she’d still said yes. Even once they lived together, it had still been a place of significance. Neutral ground. Holy ground.

Annie sat down in the lower of the two swings and leaned back, toes barely dragging in the gravel. In the one beside it, Ryan’s feet were flat on the ground, weight pulling down on the rubber until the chain pinched his sides.

“How was it?” he asked.

“Pretty easy,” she said, slowly beginning to pump. “It’s pretty much the same as amniocentesis—there was more than just the pinch they tell you to expect, but not much. It was over in like thirty seconds.”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t be there.”

She reached over and twined her fingers in his, making his arm sway in time with her.

“I know,” she replied. “You had to work.”

He stiffened, but her eyes held none of the old resentment. It was true—she really did know. And it was okay.

They’d conceived before. The first was a surprise, when they’d been married only a few months, and the tears of joy had been tinged with shock and a vague sense of panic. When she’d miscarried two months in, they’d been heartbroken, of course, but eventually both admitted to pangs of guilty relief.

The second time the stick turned blue, it was intentional—they had good jobs, a car, a house, and a strong desire to take the next step. They’d surprised their parents with it on Mother’s Day, and were immediately enveloped in a whirlwind of blue and pink, both grandmothers good-naturedly attempting to outdo each other with baby preparation. Ryan’s father, the paragon of stoicism, had cried and hugged him, tears leaking out from behind Coke-bottle glasses. Annie glowed.

When the baby spontaneously aborted in the eighth month, the pain was unlike anything Ryan or Annie had ever known. The doctors explained that there was nothing they could have done, that sometimes these things just happened, but their words fell on deaf ears. Annie blamed herself. Ryan felt helpless. In their sadness, they turned away from each other. Conversations became arguments became battles. Annie, the picture of brazen self-confidence for as long as Ryan had known her, became weepy and dependent. She resented his long hours at the hospital. He resented her resentment. They’d separated for several months, her flying back to her parents’ place in Maine, him staying in Seattle and picking up as many extra shifts as he could. But in the end, neither could stay away, and one Saturday she’d showed up on his doorstep with tears and a suitcase. Together, they’d worked through their grief. When it was done, they were a little bit harder, a few more wrinkles in their faces, but the love that had been soft and warm and all-pervasive was now iron-hard, a steel cable that suspended them above the dark pit they’d both stared into. Their love had been tested. It had passed.

There followed a long stretch where neither mentioned trying again, both of them reluctant to reopen old wounds. But all around them friends began having children, and both watched the way the other smiled when they saw small children running, the way their faces lit up when they cradled a newborn in their arms. And finally, after careful consideration and numerous late-night discussions, they had tossed out the box of condoms. Three months later, Annie was pregnant.

They’d gone back and forth on whether they wanted to test the fetus with the machine. These days, most adults went ahead and got tested, with the exception of the religious nuts and the staunch free-will atheists, who finally had a common cause to rally around. Both Annie and Ryan knew how they would go, and had shared that knowledge with each other early on. Yet the decision of whether to test a child, let alone an unborn one, was difficult, and raised a bevy of uncomfortable questions: would you abort a child that had a horribly painful death in store for it, or one that might die young? Sudden Infant Death Syndrome made frequent appearances on the machine’s little slips of paper. Was it better to die at six weeks or to never be born in the first place? And suppose your child survived to adulthood. When did you inform them of the method of their eventual demise? Some parents advocated raising children with the knowledge from birth, in the hope that never knowing a life without a prescribed death would make it easier. Others waited until the child asked, or graduated from college, or got married. Whatever the call, knowledge of the means of death quickly wrenched the title of “the Talk” from comparatively paltry topics like “where babies came from” and “you’re adopted.”

Pundits on both sides raged, but in the end, for Annie and Ryan, there was no question—if this child was going to miscarry as well, they needed to know as soon as possible so that they could induce it themselves. Abortion was far safer for Annie, and though neither of them said it, both knew that it would be easier to end things if they had less time to get attached.

Annie put her feet down, stopping herself, and squeezed his hand once before letting go. Reaching inside her jacket, she pulled out a small envelope, turning it over and over in her hands. The service she’d used had embossed it with pastel blue angels and clouds. She wedged a finger under the flap and looked up at him.

“Ready?” she asked.

A sudden lump in Ryan’s throat kept him from speaking. He nodded and reached over, placing jittery hands over hers. She broke the seal and pulled out the small, plain white card. On it, in large block letters, were printed three words:

CONGESTIVE

HEART

FAILURE

.

Ryan let out a breath. The world was spinning, sparkling at the corners. His stomach felt like he was falling.

“Do you know what this means?” he asked, voice husky and strained.

Annie turned toward him, tears glistening on cheeks pulled tight by a shaky smile.

“We’re going to have a baby,” she whispered.

Story by James L. Sutter

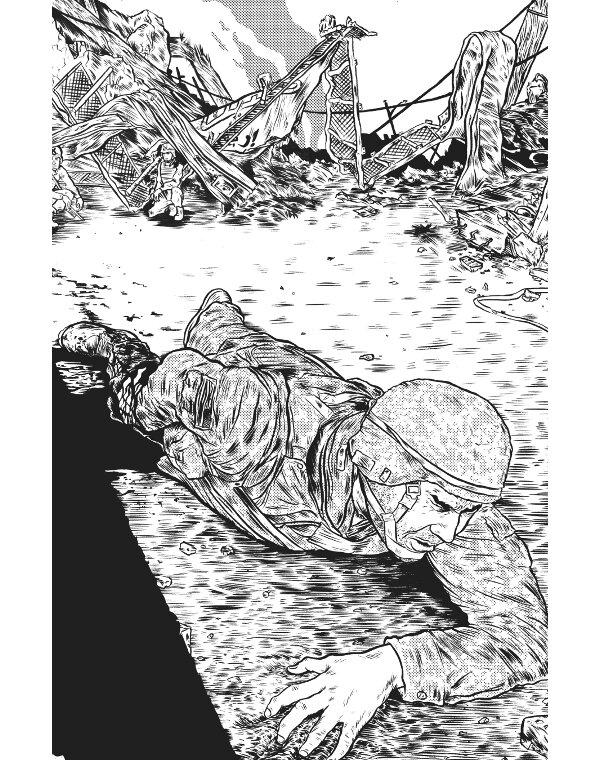

Illustration by Rene Engström

BY SNIPER