Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (10 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Monet appears to have resumed work with his old intensity within days of Clemenceau’s April visit, working almost daily throughout May and June. “I’m getting up at four in the morning,” he wrote to one of his picture dealers in June 1914.

7

Around the same time he wrote to the art critic and gallery director Félix Fénéon: “I’m hard at work and, whatever the weather, I paint...I have undertaken a great project that I love.”

8

One of the first things Monet did was to make a number of drawings. He once declared that he never drew “except with a brush and paint.”

9

He liked to promote the idea that drawing had no real place in his art—unlike, for example, the nineteenth-century painter J.-A.-D. Ingres, who claimed that drawing was “seven-eighths of what makes up painting” and who made more than five thousand drawings in the course of his long life.

10

Monet downplayed the role of drawing in his art because it smacked of forethought and went against the Impressionist ideal of spontaneously capturing an impression. However, he was actually a talented draftsman with charcoal, pen, and pencil, often making sketches in pencil or crayon as preparatory studies for his paintings. He first made his reputation as an artist with a pencil rather than a brush, since as an adolescent in Le Havre he had attracted notice with the caricatures of local worthies that he sketched and then displayed, much to the delight of passersby, in the window of a stationery shop. Later, in Paris in the 1860s, he made pencil sketches of his bohemian comrades in the brasseries.

11

Following Clemenceau’s visit, Monet evidently dug out several of his old sketchbooks.

12

One of them was, incredibly, fifty years old, and some of its ten-by-thirteen-and-a-half-inch pages were covered in rough drawings he had made as long ago as the 1860s. It was a well-traveled book, too, since others of the drawings were of the windmills he had captured in Holland in 1871. There was also, poignantly, a sketch of his

son Jean as a schoolboy—a sight that, a few months after Jean’s death, must have brought him up short.

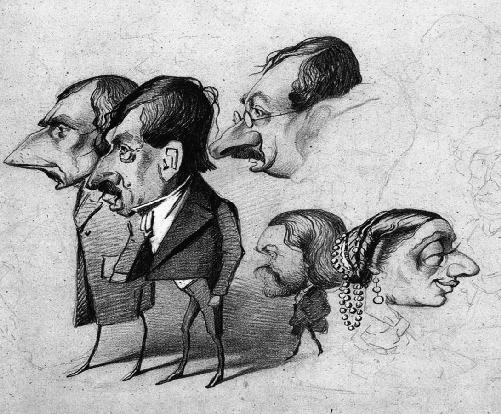

Caricatures by a youthful Claude Monet

Onto the blank pages of these well-worn sketchbooks, Monet began drawing views of his irises, willows, and water lilies, rehearsing in pencil and wax crayon—sometimes violet in color—the motifs he was planning to paint. The last page of one of the books featured a smudgy sketch, made in pencil many years earlier, of the church steeple and distant rooftops of the neighboring village of Limetz. In need of space, he turned the sketchbook upside down and in the sky over Limetz began adding—as if they were large, buoyant clouds—great clusters of water lilies. His line was swift, loose, almost dreamy. It was also assured and, it is possible to imagine, joyous—the modest and squiggly beginnings of his great project.

Monet sketch in violet crayon for one of his water lily paintings

*

MONET WAS ABLE

to resume work in the spring of 1914 because his vision had stabilized since the “dreadful discovery” almost two years earlier that he was losing the sight in his right eye. He was undergoing treatment from an ophthalmologist to delay an operation, and Clemenceau had for the moment allayed his fears of imminent blindness. “A cataract is less unpleasant than prostate trouble, I can assure you,” he informed Monet.

13

Clemenceau knew whereof he spoke, having had his prostate gland removed in 1912.

Monet still suffered from poor vision in his left eye and, as a result, limited depth perception. His color vision, too, was distorted, but he compensated, as he later told an interviewer, by “trusting both the labels on my tubes and the method I adopted of laying out my pigments on my palette.” But he also confessed that his “infirmity” gave him various remissions, periods of visual clarity that allowed him to tinker with the color balance of his canvases.

14

In any case, in the spring of 1914, his worries and complaints about his eyesight ceased for the moment, and he took the wise precautions of avoiding direct sunlight and wearing a wide-brimmed straw hat when out of doors.

Word of Monet’s sudden revival made the news in Paris, where in the middle of June a journal published an article headlined

THE HEALTH OF CLAUDE MONET

. The author immediately sought to reassure his readers: “Claude Monet is in perfect health. However, this has not always

been the case over the years, and admirers of the great artist deeply regretted that he had stopped all work. The master of Giverny no longer painted, an extremely unfortunate situation for French art, as well as for Claude Monet himself, who spent long hours in meditation, unable to take up his brushes.” But those in any doubt that the master was now back at his easel were invited to take the train through Giverny: from the window of their carriages they would be able to spot the master beside his pond, capturing “with his amazing sensitivities the marvellous colours that enchant his eyes anew.”

15

Those peering out of the window of passing locomotives may have been surprised not only by the sight of a busy Monet but also by the size of his canvases. A measure of his excitement about his “great project” was the fact that many of the canvases on which he began working in 1914 loomed over him. Early in his career, when trying to attract public attention and to get paintings accepted into the Paris Salon, he attempted several monumental paintings—the kind of showstoppers known as

grandes machines

because of the pulleys, wires, and other equipment needed to move them around the studio. In 1865 he had begun

Luncheon on the Grass

, a picnic scene filled with life-sized modern-dress figures (the women wear fashionable crinolines) that would have come in at thirteen feet high by twenty feet wide. Slathering 260 square feet of canvas with pigment ultimately proved too complex and he was forced to abandon the project unfinished.

Seemingly undaunted by this failure, in 1866 he began another large-scale canvas,

Women in the Garden

, which stood eight feet high and almost seven feet wide. His commitment to plein air painting meant—so the legend goes—that he was obliged to dig a trench in the garden of his house in Ville-d’Avray, outside Paris, and raise and lower the oversized canvas by means of a system of pulleys. His herculean efforts proved in vain, since the work was rejected by the jury for the 1867 Salon. In 1914 it featured prominently in his studio, as did the remnants of

Luncheon on the Grass

. In 1878 he had offered

Luncheon on the Grass

as security to his landlord in Argenteuil, a certain Monsieur Flament, who promptly rolled it up and put it in the cellar. Monet redeemed the canvas six years

later, by which time it had been so badly damaged by damp and mold that he cut it into three pieces.

Since then, Monet’s canvases had shrunk dramatically in size. Virtually all his paintings since the mid-1860s had been no more than three feet wide—in part, no doubt, because of his commitment to painting outdoors. The few exceptions were several paintings of his stepdaughters Blanche and Suzanne floating in skiffs on the river, done at Giverny in the late 1880s after he told his picture dealer that he hoped “to get back to big paintings.”

16

But even these canvases were less than five feet wide. The works that made his reputation and his fortune—his paintings of wheat stacks, poplars, Rouen Cathedral, London—barely ever exceeded three feet in either height or width. The water lily paintings in his spectacular 1909 Paris exhibition had been similarly modest in dimension. Most of these works were roughly three feet by three feet, with the largest still less than three and a half feet wide.

In 1914, however, Monet began working on canvases that were five feet high by more than six and a half feet wide, and his ambitions would presently stretch well beyond even these dimensions. How precisely he worked on these large canvases, especially in the early days of his great project, is difficult to know. He may have begun with small canvases on an easel beside the water, then moved into his studio and scaled up the design on the large canvases. If he began painting on large canvases in the open air beside the water, he would have needed assistance to carry them, as well as the wooden easels and his box of paints, down the steps of his studio and then more than a hundred yards through the garden and tunnel to the lily pond.

Monet may have been aided in these tasks by his gardeners, but Blanche also gave him practical assistance as in the old days when she used to follow him through the fields, pushing his canvases in a wheel-barrow and then painting her own compositions at his side. One visitor to Giverny later recalled that Blanche would “tackle the weighty easels” for Monet.

17

He could not have hoped for a more sympathetic or knowledgeable assistant. She had enjoyed some artistic success of her own: Bertha Palmer bought one of her landscapes in 1892, and she showed

her work at the Salon des Indépendants—and, like her stepfather, was rejected by the Salon.

*

If she had given up on her own painting, she now turned her attentions to helping Monet. “She’s not going to leave me at present,” Monet had written to Geffroy back in February, a week after Jean’s death, “which will be a consolation for the both of us.”

18

Indeed, the presence of Blanche, who offered both companionship and support, were as vital to Monet’s artistic resurrection in the spring of 1914 as the encouragement of Clemenceau. As Geffroy later observed, Monet “found the courage to live and the strength to work thanks to the presence of the woman who became his devoted daughter.” After Jean’s death, she began taking the place of her mother by maintaining the house for Monet and hosting friends such as Clemenceau when they came to visit. Crucially, she also “encouraged him to take up his brushes,”

19

thereby helping to end his years of sorrow and inactivity.

“MONET PAINTS IN

a strange language,” the reviewer had claimed in 1883, “whose secrets, together with a few initiates, he alone possesses.” This language was understood much better by the first decades of the twentieth century. Impressionism in general, and Monet in particular, had been the subject of numerous books and articles explaining their secrets: the seemingly impulsive brushwork and random compositions of everyday subjects of middle-class leisure and beautiful but otherwise undistinguished snatches of countryside. As early as 1867, readers of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt’s novel

Manette Salomon

were given, through the depiction of a painter named Crescent, a clear-sighted account of the aspirations of Monet and his friends. Crescent differs from the members of the “serious school,” who are “enemies of color.” These painters, trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, distrust spontaneous impressions and instead approach paintings “by reflection, through an operation of the brain, through the application and judgment of ideas.”

Crescent, by contrast, instinctively records his sensations of grass and trees, the freshness of a river, the shade along a path. “What he sought above all,” the narrator says, “was the vivid and profound impression of the place, of the moment, the season, the hour.”

20

This passage gives a remarkable account of what was soon to become Monet’s practice. But how were these scenes—with their subtle and often short-lived visual effects such as quavering leaves, fleeting shadows and glints of light—to be reproduced by pigment on canvas? How could the immaterial and impermanent be given materiality and permanency? How could the artist capture what the human eye perceived in the brief sparkle of a second?