Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (28 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Monet had never before attempted anything either on this scale or presenting such complexity. He needed to concern himself not merely

with the internal qualities of large-scale individual compositions themselves, but also with how they might work together as an ensemble to form a continuous loop. Ensuring that the perspectives in all of them remained consistent and convincing, and that the color and lighting in one fourteen-foot-wide painting harmonized with the color and lighting in the adjacent ones—portions of which were separated by more than fifty feet and painted, presumably, many months apart—were unique and troublesome challenges. Monet’s obsession with capturing subtle, transitory effects had been (as his many rages confirmed) difficult enough to achieve in paintings that were only three feet wide and that took, perhaps, a few days to paint. Yet for the past three years he had been attempting similar feats across compositions almost sixty feet wide and on works that took, not days, but months or even years to complete.

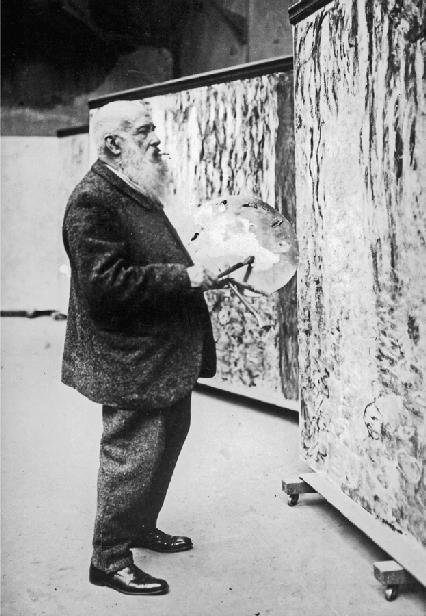

Monet, with his ubiquitous cigarette, hard at work in his new studio. His large canvases rest on easels fitted with casters for ease of movement.

MONET WAS NOT

the only one showing energy and determination that autumn. Several weeks after the photographer visited his studio in November, Monet wrote to Joseph Durand-Ruel: “And now my old Clemenceau comes to power. What a burden for him. Can he succeed despite all the pitfalls that will be laid for him? What great energy all the same!”

38

Momentous events had unfolded in Paris. French politics was becoming increasingly fractious and disordered, with opposing forces on the left and right making it virtually impossible for the prime minister and his cabinet to govern. After a duration of less than six months, the government of Alexandre Ribot collapsed in September, to be replaced by one headed by Paul Painlevé, which in turn lasted only two months. Two days after Painlevé was forced from office on November 13, the president of the republic, Raymond Poincaré, summoned Georges Clemenceau to the Élysée Palace. The fifty-seven-year-old Poincaré was famously cold and calculating. “He has a stone for a heart,” remarked another politician.

39

Poincaré’s heart was, in fact, reserved for animals, an endless succession of beloved Siamese cats, collies, and sheepdogs on whom he lavished tender affections, claiming these “mysterious creatures” were in no way inferior to humans.

40

His faith in dumb creatures

had not even been punctured by a bizarre recent event in which his wife, Henriette, while relaxing in the gardens of the Élysée Palace, was attacked and dragged into a lime tree by an escaped chimpanzee. The episode seemed to characterize the president’s tragicomic ineptitude.

41

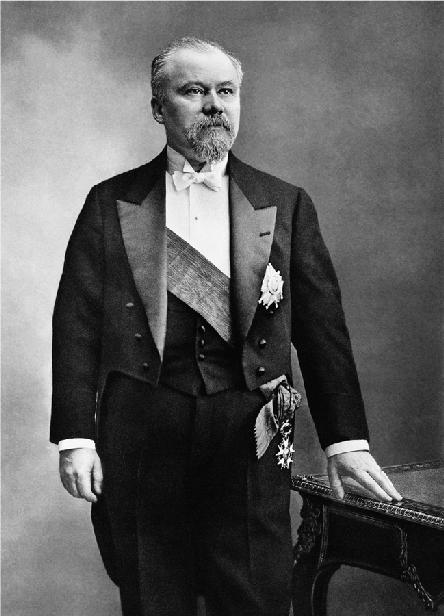

Raymond Poincaré

As president of the republic, Poincaré was far from the most powerful or important man in French politics. He was elected by the Chamber of Deputies, who usually chose politicians posing little threat to their various agendas. “I am criticized for doing nothing,” Félix Faure had declared during his term as president, “but what do you expect? I am the equivalent of the Queen of England.”

42

It was not a bad analogy, since the president enjoyed many of the powers and restrictions of a constitutional monarch. Clemenceau used a different comparison: “In the end,” he quipped, “there are only two useless organs: the prostate and the Presidency of the Republic.”

43

The president did have one important duty, which was to appoint the prime minister, the man who put together a cabinet and formed the government. But prime ministers were likewise not always the most impressive political specimens. Just as the deputies elected a weak politician who posed little challenge to them, the president for the same reason was prone to selecting a mediocre politician as prime minister. But the collapse of three successive governments in 1917—not to mention the failure of the French military offensives, mutinies in the army, and shortages of food and coal—convinced Poincaré that a firm hand was needed at the tiller. He was therefore prepared to think the unthinkable.

The decision was not an easy one for Poincaré. He and Clemenceau cordially loathed one another. “Madman,” Poincaré fumed about Clemenceau in his diary. “Old, moronic, vain man.” Clemenceau, meanwhile, skewered Poincaré with one of his famous insults, once again making an unflattering reference to a redundant organ: “There are only two perfectly useless things in the world. One is an appendix and the other is Poincaré.” He also called him “a somewhat unpleasant animal...of which, luckily, only one specimen is known.”

44

On this occasion, relations between the two men proved surprisingly affable. “The Tiger arrives,” Poincaré wrote in his diary. “He is fatter, and his deafness has increased. His intelligence is intact. But what about his health, and his will-power? I fear that one or the other may have changed for the worse.”

45

Poincaré knew nothing of Clemenceau’s diabetes, but he was aware that only a few weeks earlier the Tiger had celebrated his seventy-sixth birthday. He debated with himself, and then with fellow politicians, about whether to risk calling on this

diable d’homme

, as he called him, to lead the government. “I see the terrible defects of Clemenceau,” he wrote in his diary. “His immense pride, his instability, his frivolity. But have I the right to rule him out when I can find no one else who meets the requirements of the situation?”

46

Moreover, Poincaré knew that failing to allow Clemenceau to form a government would undoubtedly mean that this

tombeur de ministères

would claim the scalp of yet another prime minister.

On the day following the meeting the headline of

L’Homme Libre

therefore declared: clemenceau agrees to form a cabinet. There would be many pitfalls laid for Clemenceau, as Monet noted, but for the moment even some of his most hateful critics were prepared to accept his appointment. As an editorial in

La Croix

declared, making reference to Clemenceau’s medical training: “The situation is critical, and we require an energetic doctor. To do the necessary work, he will need to perform surgery.”

47

Another newspaper noted that this new government at least had one thing going for it: Clemenceau would not be campaigning against it.

48

Any doubts that Clemenceau would take a firm hand in conducting the faltering war effort were dispelled when he took for himself the

post of minister of war and, on November 19, in a speech before the Chamber of Deputies, stated his policy in three words: “

Faire la guerre

” (“Make war”). A day later he vowed “to make war, nothing but war... One day, from Paris to the most humble village, bursts of great cheers shall greet our victorious standards, twisted and bloodied, covered in tears, torn by shells—the magnificent apparition of our great dead. It is within our power to bring about this day, the most beautiful of our people.”

49

An English politician present in the Chamber that day, Winston Churchill, then Great Britain’s minister of munitions, was highly impressed by the sight of Clemenceau in action: “He looked like a wild animal pacing to and fro behind bars, growling and glaring...France had resolved to unbar the cage and let her tiger loose upon all foes...With snarls and growls, the ferocious, aged, dauntless beast of prey went into action.”

50

MONET MAY HAVE

been concerned for the political battles soon to be faced by “my old Clemenceau,” but he could hardly have failed to recognize how the appointment of his friend boded well for the Grande Décoration. After all, Clemenceau during his previous stint as prime minister had arranged, in the autumn of 1907, for the purchase by the government of one of Monet’s paintings of Rouen cathedral; the work was promptly placed on display in the Musée du Luxembourg. Also, he would have been relieved to see that, although Albert Dalimier was removed as undersecretary of state for the fine arts, Étienne Clémentel remained safely in the cabinet as minister of commerce and industry.

If Clemenceau was pledging “

la guerre, rien que la guerre

” (war, nothing but war), for Monet the slogan was “

La peinture, rien que la peinture

.” The photographs taken in November showed a massive amount of work—a body of painting that, once placed together, would cover well over one hundred feet of wall space. That vast expanse did not even include his numerous studies, including the six-foot-wide

grandes études

. But still Monet continued to paint. In January 1918 he wrote to Madame Barillon, asking for her to send a dozen high-quality large, flat

paintbrushes “as quickly as possible,” along with the dimensions of further canvases she was also shipping.

51

The scale of Monet’s ambitions were divulged to an art critic, François Thiébault-Sisson, who came to Giverny on a springlike day early in 1918 and wrote up an account of his visit some years later.

52

Monet began by describing his project as a “series of overall impressions” of his water lily pond that he hoped—as he humbly told Thiébault-Sisson—“would not be devoid of interest.” These modest intentions were at odds, as the critic soon learned, with the scale of the work. Monet’s plan, he revealed, was to paint a total of twelve large canvases, of which eight had already been completed, while the other four were “under way.” That is, he claimed to have completed eight canvases six feet seven inches by fourteen feet in size, a statement certainly borne out by the photographs taken in November 1917. Meanwhile four other paintings of similar size were in various stages of progress. The finished ensemble would therefore stretch for 168 feet, or 56 yards, around the perimeter of the desired room, which would need to be at least 60 yards in circumference and almost 20 yards across. With these dimensions, Monet’s canvases were capable of extending halfway around a room as vast as the Chamber of Deputies, which sat six hundred people. Monet was not envisaging this particular site for his work, but these dimensions prove how anything other than a room of state or a dedicated museum would have been inadequate. The “very rich Jew” imagined by Clemenceau a few years earlier was no longer a viable option. Only a large public space would suffice.

Thiébault-Sisson found Monet lively and robust, with “a smile on his lips, a cheerful light in his eye, and a most honest and cordial handshake. His seventy eight years weighed lightly upon him...The only sign of his age was his beard, totally white.” He struck the critic as optimistic about his task, believing the end of his gargantuan labors was in sight. “In a year,” he told the critic, “I shall have completed the work to my satisfaction, unless my eyes play new tricks on me.”

Rather than his eyes, Monet found himself grappling with other irritating difficulties in the early months of 1918—ones caused by the war. Labor shortages meant he had problems finding a carpenter to

build large stretchers for his canvases. Once he finally got the stretchers built, he had trouble getting them shipped to Giverny because coal shortages and lack of rolling stock meant that fewer and fewer trains were running. And because of restrictions imposed on civilians, the rare trains that did come steaming down the track refused to carry his large stretchers either as luggage or mail. To top it off, his color merchant soon had trouble meeting his demand for oil paint.

53

The shortage of paint may well have been due to the efforts of Guirand de Scévola’s camouflage unit. Along fifteen miles of front, from Rouvroy to Bois des Loges, the

camoufleurs

had recently installed 2.7 million square feet of raphia (a straw-like material) and 1.4 million square feet of canvas, all painted and used to disguise roads, canals, airfields, and trenches, and otherwise to deceive the Germans. In June 1917 a studio of

camoufleurs

had painted a huge trompe-l’oeil of an attacking army that was raised dramatically above the trenches at Messines, intended to simulate a wave of three hundred soldiers “going over the top.” Meanwhile, a “fake Paris” was being created along the Seine near Maisons-Laffitte, fifteen miles downstream from the real thing, complete with sham factories and railways, and even a dummy Champs-Élysées—all done to draw the German bombers away from Paris.

54

A report prepared by none other than Clémentel himself stated that for camouflage the French military required ten thousand tons of jute each month.

55