Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (54 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

In fact, it was Monet’s deteriorating reputation rather than his deteriorating canvases that brought the forlorn expression to Clemenceau’s face. It had not escaped his notice that what was officially known as le Musée Claude-Monet à l’Orangerie des Tuileries had opened to little fanfare. By contrast, two days later, in New York, the

Panthéon de la Guerre

would be inaugurated in Madison Square Garden before a crowd of 25,000 people and a live radio broadcast. Monet received no such attention. Clemenceau observed bitterly that a sign announcing a dog show in another part of the building (for the growling canines had returned to the Orangerie) was much more prominent than the sign announcing the inauguration of the Musée Claude-Monet.

A number of respectful and flattering reviews appeared, to be sure, such as the one in

Le Populaire

. It praised the canvases as a summation of the master’s aesthetics that revealed “the penetrating intensity of his vision and the tremendous flexibility of his brush technique.”

5

But other reviews were less than complimentary. “The work of an old man,” pronounced the

Comoedia

, France’s most important daily arts newspaper. “One senses the fatigue,” sniffed

Le Petit Journal

.

6

The painter Walter Sickert complained that they were too big, while even before they were marouflaged to the walls of the Orangerie an assistant curator at the Luxembourg Museum—Robert Rey, nominally in charge of looking

after these works—summarily dismissed them: “For me this period is no longer Impressionism, but its decline.”

7

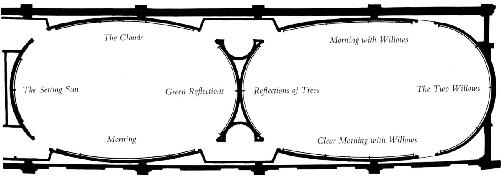

Original plan of the Monet galleries at the Orangerie

The history of French art was filled with Ozymandias figures. As one of the prime examples, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, had observed: “Many people who had great reputations are nothing but burst balloons now.”

8

Even before Monet was laid to rest, it appeared that his balloon might be about to burst and that, like Meissonier, he would pay for the fabulous success of his lifetime with scorn and obscurity in the hereafter. Some of the obituaries had been all too eager to point out his supposed shortcomings, along with those of Impressionism in general. One of them reported that Impressionism was “a doctrine against which a generation reacts with good reason,” while the obituary in

L’Écho de Paris

took Monet to task for creating in his “long and peaceful old age” paintings that were nothing more than “scattered bits of fairy gossamer. We prefer the surprising feats of virtuosity of his youth and maturity.” In 1927 a special issue of

L’Art Vivant

devoted six articles to Monet. One of them, by Jacques-Émile Blanche, was filled with damning invective: Monet’s paintings were merely “postcard niceties of a certain American taste” purchased by the vulgar nouveaux riches.

9

Several months after Monet’s works had been inaugurated in the Orangerie, Jacques-Émile Blanche was at it again: “These spots, these

splashes, these scratches inflicted on the surface of canvases of who knows how many square meters...a theatrical set designer with his bag of tricks could succeed in producing much the same effect.”

10

Mixed in with his complaints about Monet’s canvases were comments about the ugliness and sterility of the two oval rooms in which they were displayed: they had the “solemnity of the hall of an empty palace.” He could not resist pointing out that few people were present in these rooms and that no one lingered for long. Viewing the paintings, he observed, was a disagreeable experience due to the lack of seats, the hard marble-like floor, and the meager light source.

Clemenceau would hardly have disputed the dearth of visitors and the poor light. More than a year after the inauguration, in June 1928, he was disappointed by his visit to the Orangerie. “There wasn’t a soul there,” he lamented. “During the day forty-six men and women came, of whom forty-four were lovers looking for a solitary spot.”

11

In 1929 he complained that the paintings were exhibited in darkness: “On my last visit, the visitors asked for candles. When I complained to Paul Léon, I received nothing but a pale smile.”

12

Another visitor compared the rooms to a dark and featureless crypt, claiming that he succumbed almost instantly to a migraine.

13

The paintings were subjected to further indignities besides the poor light and lack of publicity. The oval rooms were used to stage other exhibitions. On one occasion, Flemish tapestries were hung in front of the paintings; at another point, water leaked through the vellum skylight and dripped down the front of the canvases. At other times, one of the two rooms was used as a storage area.

14

Such a combination of indifference, hostility, and neglect prompted Paul-Émile Pissarro, the youngest son of the painter and Monet’s godson, to claim that Monet had been buried twice: once in 1926, after his death, and a second time in 1927, with the opening of the Orangerie.

15

MONET’S REPUTATION WAS

kept alive in the years following his death by his dwindling band of surviving friends. Clemenceau was to perform one final service: the publication in 1928 of a book entitled

Claude Monet:

Les Nymphéas

. It was part of the Paris-based publisher Plon’s “Noble Lives, Great Works” series, whose earlier volumes included studies of such luminaries as Racine, Victor Hugo, and Saint Louis of Toulouse. A year later another faithful friend, Sacha Guitry, paid tribute to Monet by likewise placing him among the pantheon of French heroes. In October 1929 his four-act play

Histoires de France

opened at the Théâtre Pigalle in Paris. It featured inspiring episodes from French history, with actors taking the parts of Joan of Arc, Henri IV, Louis XIV, Napoleon, and Talleyrand. Guitry did not fail to include the events of Monday, November 18, 1918, when Clemenceau came to Giverny and Monet pledged to donate canvases to the state. The role of Monet was played by Guitry himself, who gave, in the words of one reviewer, a “remarkable impersonation.”

16

Clemenceau died the following month, in November 1929. In the years that followed, the critical curses fell steadily on Monet and Impressionism, and in particular on Monet’s final works. In 1931 a guidebook to Paris’s museums could still extoll Monet’s paintings in the Orangerie as a “colorful poem of a refined sensibility” that transcended the limits of painting.

17

Yet even an old ally, Arsène Alexandre, lamented that in these last works Monet had abandoned the “direct communication with nature” found in his early paintings in favor of conveying “internal impressions.” He had been the leader, wrote Alexandre, of a “frantic cult of color” whose time had come and gone.

18

Such were the critical suspicions of Monet that a retrospective exhibition of 128 of his paintings staged at the Orangerie in 1931 began with a series of pleas and apologies. The curator, Paul Jamot, admitted that Impressionism had fallen out of critical favor among young painters and critics, “many of whom have moved beyond indifference and reached a stage of disdainful disapproval.”

19

He allowed that Impressionism was excessive in exalting the sensuous over the intellectual, the eye over the brain. This emphasis had led to a reaction that sought to restore “the principles of solidity, order and composition.” Jamot called this movement a “

retour classique

” (return to the classics). It had become fashionable to argue that, later in their careers, many of the Impressionists and

Post-Impressionists had actually turned for their inspiration to the firm contours of classical art. But of course Monet with his shifting fogs and shimmering prisms of light could never be counted among those who embraced the solidity and reassurance of bold, clear lines and hard-edged, simplified forms.

20

The 1931 retrospective at the Orangerie included a small section called

Les Nymphéas

. However, the works on show consisted merely of five small canvases of the lily pond sent by Michel Monet from among the unsold works in the grand atelier. The curators evidently had no appetite to put on display any of the large-scale canvases that Monet had painted in the last dozen years of his life. Some twenty of these paintings could still be found in the studio, languishing unseen and unsold. The catalogue was dismissive of such late works, noting that Monet’s problems with his eyes meant that many of the canvases consisted of “scatterings of color increasingly detached from the constraints of visual reality.”

21

Reviews of the exhibition were as vicious as they were sparse, as critics took the opportunity for further swipes at the donation to the Orangerie. The two oval rooms of painted canvas resembled, according to one critic, Alexandre Benoît, “the first-class cabin of an ocean liner.” The paintings of

Les Nymphéas

were, he said, a catastrophe, the “truly pitiful crowning of Monet’s career.”

22

That same year Florent Fels, who six years earlier had seen (and been impressed by) these large canvases, asked a bit plaintively: “What will become of his last panels?” He praised them as “a sensual delirium of pure color”—although this sort of work, he bleakly acknowledged, did not match the “virility of design and form” demanded by young painters.

23

Indeed they did not. A year later, in 1932, the Cubist painter André Lhote, another aggressive and persistent anti-Monet crusader, claimed the Impressionist master had committed “artistic suicide” at the Orangerie, where the “soul of the Ophelia of painting is dragged down ingloriously by a shroud of waterlilies.”

24

Such criticism revealed how Monet had become a victim of the “return to order” that followed the trauma of the Great War, when there was a call in many quarters for a nostalgia-tinged, pastoral subject

matter conjuring the antebellum world.

25

This world had been captured evocatively in Monet’s wheat stacks, poplars, and riverscapes—all of which retained their commercial and critical appeal—but the Grande Décoration responded to this call neither in its hazy, high-keyed style nor in its exotic subject matter, which appeared to have little to do with rural France. For Lhote, Monet in his last decades had perversely disdained “landscapes that only begged to be copied”—the supposedly timeless views of rural Normandy—in favor of concentrating on his garden pond.

26

Monet may have submerged himself, in Lhote’s opinion, in stagnant, florid waters. Unlike Ophelia, however, he was destined to rise from his watery grave.

IN 1949 A

newspaper reported that each year Félix Breuil, Monet’s old gardener, made the journey to Paris to visit the Orangerie.

27

Breuil had been one of the few regular visitors over the previous two decades to what, in 1952, a painter called a “deserted place in the heart of the city.”

28

However, things were beginning to change. In the years after World War II, the Orangerie became a place of pilgrimage for many enthusiastic young Americans who wanted something different from the carefully controlled, Cubist-inspired geometrical constructions—the “virility of design and form”—that had dominated much of the previous generation of avant-garde painters. A Parisian gallerist later claimed that the American art students who came to France on the GI Bill in the late 1940s and early 1950s “all rushed like flies to one place: the Orangerie, to look at the

Nymphéas

by Monet, those colored rhythms with no beginning or end.”

29

Here they found what appeared to be exuberant and spontaneous expressions, luxuriant nature abstracted into pullulating colors and visual grace.

One of these ex-soldiers studying in Paris, Ellsworth Kelly, wrote to Jean-Pierre Hoschedé asking if he might visit Giverny. The house and garden had retained much of their magical allure in the years following Monet’s death, when the rue de Haut, the road running past his house, was christened rue Claude-Monet. In May 1939 the garden received

the ultimate in fashion accolades when it was featured in the pages of the French edition of

Vogue

, which described it as a “paradise of flowers.” The photographs were taken by none other than Willy Maywald, soon to become famous for his work with Christian Dior. But during and after the war, the property fell into disrepair. A year following the

Vogue

spread, Blanche left Giverny for Aix-en-Provence, dying in Nice in 1947 at the age of eighty-two. Following her departure, the upkeep of the house was paid for by Michel Monet and Jean-Pierre Hoschedé. The latter remained in Giverny, in the Maison Bleue, while Michel—“the solitary Michel Monet,” as a newspaper called him

30

—moved twenty-five miles south to the village of Sorel-Moussel. There he lived among a clutter of Monet’s unsold paintings and his own trophies from African safaris, including a pet monkey.