Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (52 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

At least his relations with Monet gradually began to thaw and improve. Once again he began to look forward to lunches in Giverny. “In my case, my heart is weakening,” he wrote to Monet in July. “I have only a faint pulse. I must learn to live with this, and my general way of life is not altered. However, I must take precautions. The first of them is that I must go to lunch on Sunday with Monet. This is better than digitalis and the antics of our doctors in their pointy caps.”

16

Ominously, he was forced to cancel this visit to Giverny because, as he apologized, “I felt a great fatigue.”

17

The Tiger’s legendary energy was finally beginning to flag. Over the next few months his letters to Monet were uncharacteristically filled with references to his own poor health. In a kind of emotional blackmail, he even raised the specter of his death, halfheartedly joking that he would remain in the Vendée for a few more weeks “unless I stay there because of a final immobility.” In August he informed Monet that he hoped to live long enough to see the opening of the “Salon Monet.”

18

*

THE DEATHS OF

those closest to him often seemed to spring Monet into action at his easel, almost as if he believed the act of furiously painting might hold his own death at bay. The tragic passing in 1899 of his stepdaughter Suzanne Hoschedé-Butler had appeared to release something within him: a short time after her death, after having not painted for a year because of his disillusionment with the Dreyfus Affair, he produced a dozen views of his Japanese bridge and then scores of canvases of London. Likewise, the death in 1914 of his son Jean, harrowing as it was, shook him from the long depression into which he had fallen after his beloved Alice died. The Grande Décoration was conceived and started within months of Jean’s funeral.

Monet’s most startling reaction with his paintbrush had been at the deathbed of his first wife, Camille. She died in Vétheuil in September 1879, after horrendous sufferings. Monet was, quite naturally, devastated. But as he told Clemenceau many years later: “I found myself with my eyes fixed on her tragic brow, in the act of automatically studying the succession and duration of fading colours that death came to impose on her motionless face. Shades of blue, yellow, grey, what have you.”

19

He began a rapid sketch of her postmortem features, and the result was

Camille Monet on Her Deathbed

. The act showed him painting, quite literally, in the face of death. If today his act seems callous, it must be put in the context of a time when families photographed themselves posing with their deceased loved ones, and when John James Audubon, early in his career, made money by painting deathbed portraits and, on one occasion, having his subject—a minister’s son—exhumed for the purpose.

20

The sudden death of Marthe yet again seemed to send Monet eagerly to his brushes and paints. “It’s a true resurrection,” he rejoiced of his improved eyesight and renewed activity.

21

André Barbier claimed that he turned up in Giverny one day in May 1925 (only a few days, presumably, after Marthe’s funeral) with a collection of colorful specimens: exotic butterflies, seashells, minerals, and reproductions of Degas’s drawings. “Monet examined all of them with joy—proving to me that he saw every nuance.”

22

The new Zeiss lenses undoubtedly had much to

do with this well-nigh miraculous recovery, although he was still occluding his left (unoperated-on) eye. In any case he was elated. “I’ve finally regained my true sight,” he told Marc Elder, “which for me is like a second youth, and I have begun to work from life with a strange euphoria.”

23

Indeed, Monet claimed to one and all throughout the summer and autumn of 1925 that he was back to work “as never before” on the Grande Décoration, painting with “passion and joy” despite the uncooperative weather, which on one occasion left him completely drenched.

24

By October he had told Elder that he was putting the “finishing touches” on the paintings. “I don’t want to lose a moment until I have delivered my panels.”

25

To Barbier he claimed that this momentous date would finally arrive in the spring of 1926

26

—though his proposed deliveries had always been mirages that shimmered tantalizingly on the horizon before suddenly receding and evaporating like the fogs he had once painted on the Seine. Despite his claim about finishing touches, the lower right-hand corner of

The Setting Sun

still remained blank, as if Monet wished to emphasize the provisional and incomplete nature of his efforts—or perhaps because he simply could not bear to bring his labors to an end, and to let the sun finally set on his Grande Décoration.

Clemenceau was naturally delighted at this new and unexpected development, writing that he was reminded of the Monet of “the good old days.”

27

“You will make a few more miracles,” he wrote to him at the end of November. “I’ve come to believe you can do anything.”

28

Yet doubts and anxieties lingered. His newfound faith in a resurrected Monet was not enough to make him resist, a month later, the pointed reminder that “I shall be happy if, as you have definitively stated, you can, in the spring, enjoy a triumph like no other.”

29

A few weeks later, pressing the point home, he reiterated his concerns about his health: “I don’t want to die without seeing your results.”

30

He may have been exaggerating his physical plight, but he was still in poor health. He suffered from influenza throughout January 1926, for which he was treated with iodine and suction cups on his back. Around the same time he began a new treatment for his diabetes, arranging with the American ambassador to France, Myron T. Herrick, for shipments of American insulin

(superior, he believed, to the French variety) to be smuggled into the country in diplomatic bags—an illegal task for which the ambassador would be rewarded, he assured him, “either in this world or the next.”

31

He was given daily injections by his faithful valet, Albert Boulin.

It was, however, to be another friend that Monet lost that year. At the beginning of April, Gustave Geffroy died in his book-filled apartment at the Manufacture des Gobelins. His beloved sister Delphine had passed away a week earlier, the trauma of her death worsened by her frantic hallucinations and violent fits that exhausted Geffroy—her devoted caregiver of many years—both physically and emotionally. He died of a cerebral embolism a few days after her funeral. On April 7, at the cemetery in Montrouge, Clemenceau walked at the head of a large funeral cortège that included many writers and government officials, including the members of the Académie Goncourt and Paul Léon. “His life and his death are a great example,” Clemenceau intoned at Geffroy’s graveside, his voice shaking with emotion. “He struggled, he suffered, he was happy, and we must not be ashamed to say that he experienced life. His work is enough for us to judge him and to justify our admiration and our love.”

32

That morning Clemenceau had written to a friend: “I leave in a few minutes to bury a part of my past. I shall be seeing too many friends who are dead without being in the cemetery.”

33

Although Monet no doubt qualified for this unflattering description, his poor health prevented him from joining the mourners in Montrouge. By the spring of 1926 it had become clear that he was in a worse state than Clemenceau. He was fatigued and suffering from pains successively diagnosed as inter-costal neuralgia and gout. “I suppose that your doctor had to ban your little glass of Schnick, which will make you curse,” joked Clemenceau.

34

Monet also suffered for several months from tracheitis, which made it difficult for him to eat, drink, and smoke.

Visiting Monet in April, shortly after Geffroy’s funeral, Clemenceau found him in decline. “The human machine is cracking on all sides,” he reported to a friend. “He is stoical and even cheerful at times. His panels are finished and will not be touched again, but he’s unable to let them go. The best thing is to let him live day by day.”

35

Clemenceau knew by this point that the “Salon Monet” would open only with the death of the artist. At some point in 1925, Monet had assured him that he would make the donation after all, but that it would be a posthumous one. “When I am dead,” he told Clemenceau, “I shall find their imperfections more bearable.”

36

Clemenceau also knew by this point that Monet’s death could not be far off. The painter no longer possessed the strength to walk around his garden, the expense of which was so great that he began contemplating giving it up. Such a measure would have been drastic and agonizing, since his garden, unlike painting, gave him nothing but pleasure. The company of Clemenceau, however, had temporarily raised his spirits during the visit that April. “I reminded him of the times of our youth, and this cheered him up. He was still laughing when I left.”

37

MONET CONTINUED TO

receive visitors. On a May afternoon humming with bees, Evan Charteris arrived to interview him for a book on John Singer Sargent. Charteris, the future chairman of the Tate Gallery in London, found the painter “conversing in his garden with two devout visitors from Japan, who presently took their leave with reverential obeisances.” Charteris was impressed with the painter’s vitality. “The vigour of his voice and the alertness of his mind pointed to an astonishing discrepancy between constitution and age. He struck a visitor as at once gay and kindly, keen in his wit, and emphatic in his prejudices.” Even Monet’s occluded left eye and thick Zeiss lenses did not detract from his impression of alert and responsive acuity. His right eye, “magnified behind the lens of powerful spectacles, seemed to possess some of the properties of a searchlight and be ready to seize on the innermost secrets of a visible world.”

38

Around the same time, the painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, spying Monet in his garden from the chemin du Roy, was surprised by the painter’s “robust appearance.”

39

He was not the only one peeping over the fence at Monet. As he observed a short time later, Monet was regarded by many foreigners, especially Americans, as one of France’s greatest celebrities: a figure on par with Louis Pasteur and Sarah Bernhardt.

40

Later that summer another visitor to Giverny, the poet Michel Sauvage, witnessed “a line of cars” filing slowly past Monet’s “beflowered paradise.” “Many admirers of the painter come here each day,” he wrote, “among them many foreigners. They stop, look round, and would like to enter, but no visitors are received.”

41

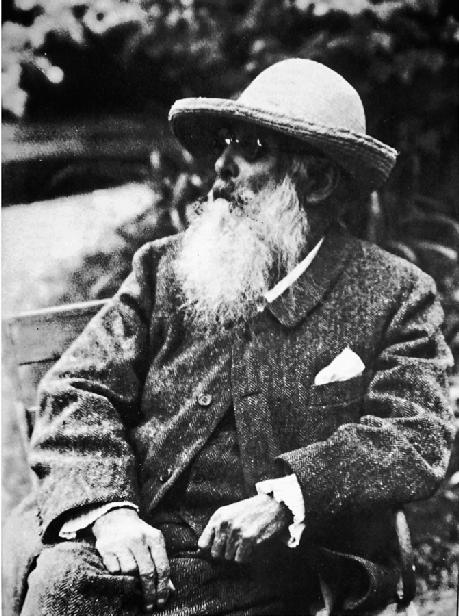

Monet in the summer of 1926

To Louis Gillet, Monet was likewise still powerful and radiant. “Age only added to his majesty,” he claimed, comparing him to the Manneporte, the massive rock formation at Étretat that he had painted so many times. He was “besieged by the waves and assaulted by storms” but still defiantly standing.

42

Yet no matter how impressive the figure he cut, by the summer of 1926 Monet was rapidly losing weight as well as strength. In June he was too unwell to attend the wedding in Giverny of his granddaughter Lili Butler to Roger Toulgouat. For two weeks he was unable to leave the house. Visits from all friends except Clemenceau, who came at the end of the month, were canceled. “He’s getting old, that’s all,” Clemenceau bleakly observed.

43

He managed to lure him into the garden and then to eat something. A few days later Monet was well enough to entertain other visitors, the painters Édouard Vuillard and Ker-Xavier Roussel, along with Vuillard’s niece Annette and her husband, Jacques Salomon, who drove the party to Giverny in a red Ford convertible. Salomon found Monet surprisingly short but admired his “magnificent head.” He noted that the painter “wears thick glasses, the left eye entirely masked by a dark lens, and the other is extraordinary, as if it were hugely enlarged by a magnifying glass.” Monet served his guests duck seasoned with nutmeg and treated himself—despite concerned looks from Blanche—to great swigs of white wine.

Any impression of infirmity was cast aside when Monet took his guests into the grand atelier. “On twelve or fifteen canvases two meters high by four or six wide,” Salomon wrote, “are the magnificent landscapes...We moved the heavy frames around to place them in the order in which they will be exposed in the rotunda.” They were, he declared, “the work of a colossus.”

44

Vuillard, himself the painter of large-scale decorations, was stunned. Later, trying to explain them to a fellow painter, he was struck dumb: “It’s beyond words! It has to be seen to be believed!”

45