Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (46 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Clemenceau was, however, the most forceful and articulate prophet of doom, and it was to him that the

World

immediately turned for a quote. Did Clemenceau, the newspaper wondered, believe that America had fulfilled its duty of solidarity to the Allies? The Tiger announced via a telegram from Belébat that he would sail to the United States in November, at his own expense, to provide a response to the American people in person, in order, as the

New York Times

reported, “to restore the prestige which France has lost in the United States.”

25

Some French newspapers celebrated the return of Clemenceau to the world stage. “Whatever may be the results of the voyage we must acknowledge the grandeur of the gesture,” one reported. “Friends and

adversaries will render homage to the old man, who, withdrawn from the ardent battle of ideas, now voluntarily reenters the arena, not to indulge in vain polemics, but to speak to the world once more the clear language of France.”

26

But not everyone was eager or pleased to have the Tiger once more on the prowl and possibly straining Franco-American relations by reproaching the Americans for not ratifying the Treaty of Versailles or living up to their part of the bargain. Clemenceau did little to allay their fears, dramatically announcing: “I am going to talk squarely to America.”

27

A journalist for an English newspaper, interviewing him on the eve of his departure, found that he had lost none of his intimidating manner. He could “growl as ominously as in the old days. He can snap formidably.” Wearing his omnipresent gray gloves, he beat the table with his fists and offered opinions—“impetuous, scathing, devastating”—that were “not for publication.”

28

The editor of

Le Matin

, writing in an American paper, sighed that “France knows that not much good can result from this trip and France fears that very much evil may come of it.”

29

Clemenceau’s enemies had not counted on his fame and charisma as a conquering hero. He arrived in New York on November 18, aboard the French liner

Paris

, to a rapturous welcome as the “hero of the World War” (the

New York Times

) and “the chief artisan of Allied victory” (the

New York Tribune

). Sirens blared in the harbor and the band of New York’s Street Cleaning Department serenaded him from a tugboat. Blizzards of tickertape and torn-up telephone directories fell across the streets of Manhattan as he made his way to City Hall. The appropriate dignitaries turned out to greet him, and from Washington came a telegram from Woodrow Wilson. Clemenceau stayed at the home on East Seventy-Third Street of Charles Dana Gibson, the owner of

Life

magazine, whose wife, Irene, found him “a darling old man and not the least bit difficult to please.”

30

He toured the American Museum of Natural History and addressed the masses at City Hall and the Metropolitan Opera House. He dined with Ralph Pulitzer at the Ritz-Carlton and, rising at four

A.M.

, went out to Oyster Bay to doff his hat and lay a wreath at Teddy Roosevelt’s grave. Journalists were impressed at how his fluency in English allowed him to express his caustic witticisms “with a sort

of grim delight and sly malice.”

31

But not all his comments were grim or sly: he gallantly observed that American women were even more beautiful than fifty years ago.

32

Clemenceau in New York, November 1922

Not everyone, to be sure, was seduced by Clemenceau. He had some harsh words for his American hosts, announcing that he would have pressed on to Berlin in 1918 had he known what little effect the Treaty of Versailles would have on Germany. On the floor of the Senate he was condemned by William Borah of Idaho; other isolationists feared he was trying to lure American soldiers back to France to enforce the Treaty of Versailles. They also feared that he wished to impoverish the Germans by forcing them to pay reparations—an act that, Senator Gilbert Hitchcock argued, would drive Germany “into the arms of the Bolsheviki.”

33

From New York, Clemenceau went to Boston, where the mayor presented him with a safety razor as a gift. (“He is sorely puzzled.”)

34

Then came Chicago, St. Louis, Washington, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. “I am going back to France in a very few days now,” he told a newspaper in December, as the tour approached its end, “to tell my countrymen that we need have no fear, America still is with us, her heart has not changed.” But he was still as pessimistic as ever: “Pray the Lord that war will not have broken out by the time I get back.”

35

ON THE DAY

after Clemenceau arrived in New York,

Le Figaro

carried an article celebrating Monet as having “a miraculous eye.”

36

This familiar statement about his preternatural vision was becoming ever more ironic. By December his eyesight had become so impossibly dim that he finally overcame his trepidations about an operation. His wish, he told the returning Clemenceau, was that surgery should take place as soon as possible, “around the 8th or 10th of January, because I can no longer see very much.”

37

The operation, performed on his right eye by Dr. Coutela, duly took place on January 10, at the Clinique Ambroise Paré in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine. The first of the two planned procedures was an iridectomy: the removal of part of the iris in his right eye. A follow-up procedure, an extracapsular cataract extraction, was scheduled for a few weeks later.

The operation was relatively straightforward but inevitably involved high levels of discomfort and a lengthy and delicate convalescence. The local anesthetic consisted of injections of cocaine into the optic nerve to numb the cornea.

38

Following the operation, Monet would be required to lie still in bed in the clinic for ten days, in complete darkness, with both eyes shaded and without a pillow. Since the hardiest and most patient soul would have been challenged by this regime, it is hardly surprising that Monet did not cope well. Dr. Coutela’s notes reported that the operation went according to plan even though the patient became nauseous and even vomited, “exceptional and unforeseeable reactions, caused by his emotion, and extremely awkward and alarming.”

39

Im mediately following the operation, Monet saw colors with great intensity

and saturation, relishing “the most beautiful rainbow one could imagine.”

40

But these glorious effects did not last. He was forced to undergo the strict and prolonged regimen of lying absolutely still with both eyes bandaged, subsisting on a diet of vegetable broth, lime tea, and a mysterious meat, variously labeled “duck” or “pigeon,” that a nurse spoon-fed into his mouth.

41

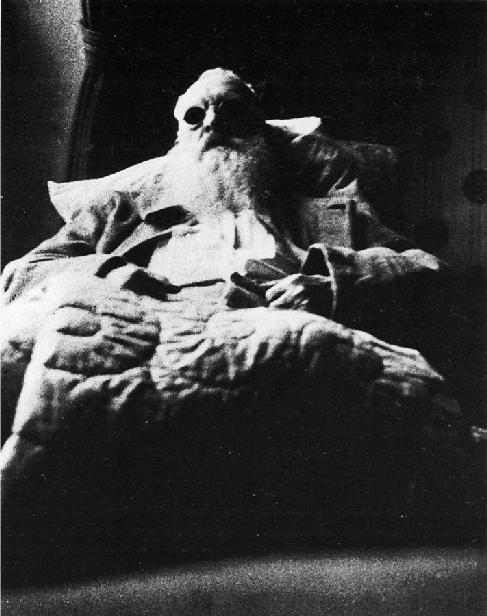

Monet in bed after his cataract operation

The bandages were occasionally removed for the application of eyedrops and further doses of cocaine. A 1906 treatise on the use of cocaine in eye operations reported that the drug’s toxicity caused “many accidents and alarms” and that it therefore needed to be used with caution.

42

A guard was usually stationed beside patients following these injections to ensure they did not become delirious from the cocaine and remove the dressing or otherwise cause problems. Monet was certainly a high-risk patient. Another ophthalmological treatise claimed elderly patients, especially heavy drinkers, were prone to delirium when both eyes were bandaged.

43

Hoschedé claimed that no guard was stationed beside Monet, with the predictable result that, in a fit of pique or panic, he one day ripped off his bandages, potentially jeopardizing his eyesight.

44

The devoted Blanche was at his bedside at the clinic in Neuilly for much of this disagreeable recuperation. “He was so nervous and overex-cited,” she reported, “that he was moving all the time.”

45

He rose from his bed on several occasions, ranting that blindness would be preferable to lying still. He eventually calmed down, she wrote, but his fits of exasperation impaired his recovery such that his stay in the clinic needed to be extended. He was in fact not discharged before he underwent

the second procedure, the extracapsulary cataract extraction that took place on the last day of the month. Once more the anxious, querulous patient was prescribed a course of complete immobility.

MONET WAS FINALLY

discharged in the middle of February, having spent a total of thirty-eight days in the clinic. The state of his vision was still uncertain, but he celebrated his freedom by going with Clemenceau and Paul Léon to see the Orangerie. He had been disappointed the previous September when he stopped by the building following his first consultation with Dr. Coutela. On that occasion his poor eyesight did not conceal from him the fact that work was by no means progressing expeditiously. “No workers at all. Absolute silence,” he had complained to Clemenceau. “Only a little pile of rubble by the door.”

46

Three months later, in December 1922, the refurbishment of the Orangerie had received legislative approval, with the state pledging 600,000 francs toward the project. In the meantime, as construction progressed, the Orangerie continued to be used as an exhibition space. A month after Monet signed the contract for his donation, the annual “Exposition Canine” took place at the Orangerie as usual, with a thousand dogs on show, the small ones “yapping in their cages,” the large ones “growling and howling like wolves.”

47

Also, a “Canadian Exhibition Train” was being planned for 1923. Thirty carriages of a railway train filled with displays of hundreds of Canadian products and artifacts—canoes, furs, paintings, along with dioramas of forests and trappers—were due to be arranged in the Tuileries, including some on the terrace of the Orangerie.

Le Bulletin de la vie artistique

protested that, with the Orangerie undergoing its extensive renovation for Monet’s donation, the venue should be off-limits to such temporary exhibitions. However, the minister of commerce and industry, Lucien Dior, defending the Canadian exposition, responded that the high cost of the renovations meant that Léon had agreed “the same facilities could be used for both events.” The display of Canadian beaver pelts and canoes might impede construction, but on the other hand they would provide some much-needed revenue.

48